Scientists Reveal the 3D Structure of the ZAK Protein That Detects Cellular Stress

The latest research on the ZAK protein, published in Nature, gives us the most detailed structural look ever at one of the cell’s key stress detectors. This new work comes from a collaboration between scientists at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich (LMU), and it offers a clearer picture of how ZAK identifies ribosome collisions inside cells and triggers protective signaling pathways. Because this protein plays a major role in responding to damage from sources like UV radiation, nutrient deprivation, and toxins, mapping its structure opens up new possibilities for designing highly targeted drugs that fine-tune stress responses.

This study marks the first time scientists have been able to visualize part of the ZAK protein’s structure in 3D at near-atomic detail. Even though they captured only about one-third of the full protein, that portion provides crucial insights into how ZAK becomes activated when ribosomes stall and collide. The research team emphasizes that understanding this mechanism is essential for developing medical treatments that act on specific regions of the protein rather than relying on broad, side-effect-prone kinase inhibitors.

What the ZAK Protein Does and Why It Matters

ZAK is a stress-responsive kinase, meaning it adds chemical groups to other proteins during stressful conditions to trigger protective responses. When a cell is under stress—whether from UV light, toxins, viruses, or a lack of nutrients—the ribosomes that normally translate messenger RNA (mRNA) into proteins can slow down or stall. When many ribosomes get stuck on the same mRNA strand, they collide. The cell interprets this collision as a danger signal, and ZAK is the protein responsible for detecting that collision and firing off downstream signaling pathways.

Earlier research from 2020 showed that ribosome collisions directly activate ZAK, but scientists didn’t yet understand which parts of the protein recognized the ribosome or how the activation mechanism worked. That is what the new study set out to uncover.

How the Researchers Investigated ZAK

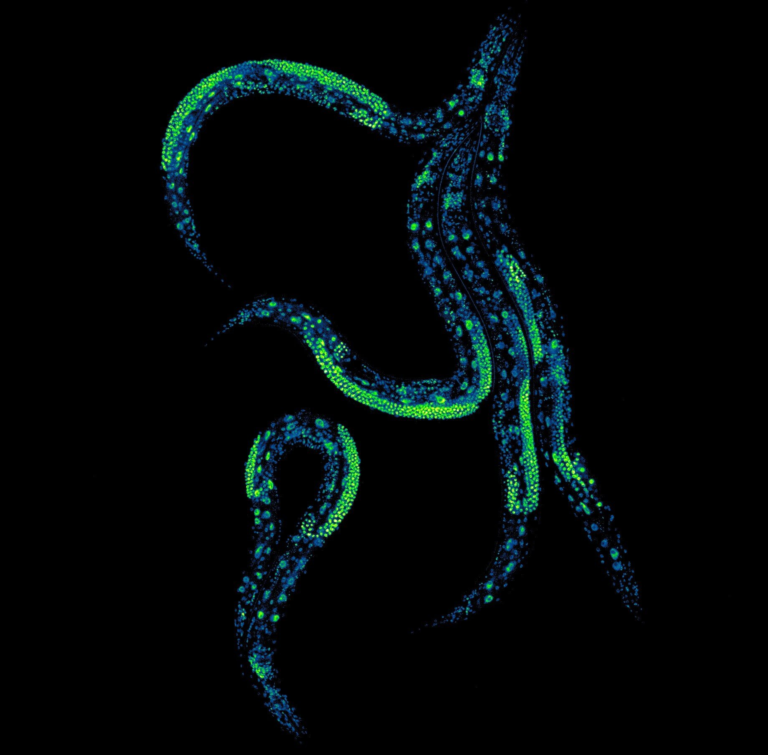

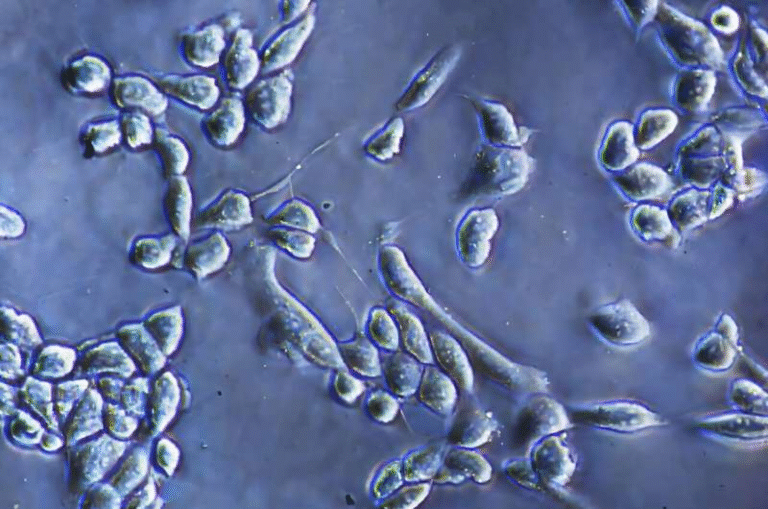

To study ZAK in action, the Johns Hopkins team engineered human cells to overproduce inactivated ZAK proteins, since normally the protein is not abundant. They then treated the cells with a drug that forces ribosomes to pause during translation, creating controlled ribosome collisions. The modified ZAK proteins carried a molecular tag that made it possible to isolate activated ZAK bound to ribosomes.

Once the researchers collected enough samples, they shipped them to LMU in Munich, where experts in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) imaged the ribosome-ZAK complexes. Achieving a suitable cryo-EM map required hundreds of samples and two full years of refinement, underscoring how difficult it is to capture flexible proteins like ZAK.

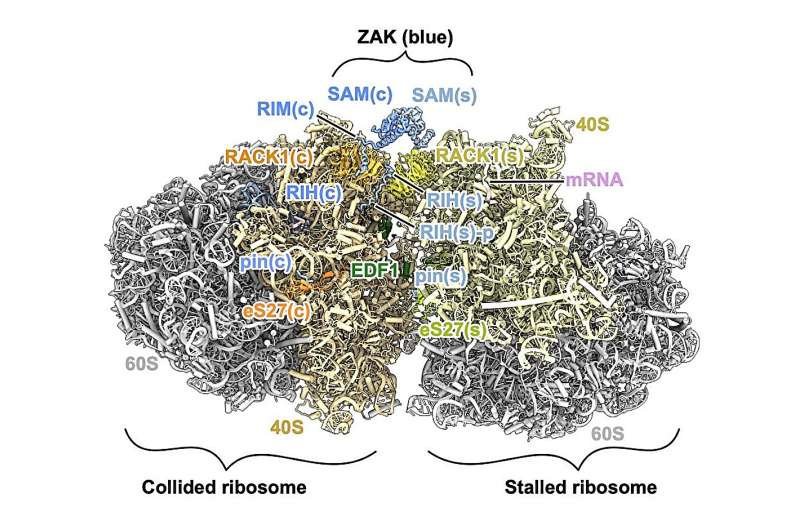

Eventually, LMU researchers spotted a promising structure showing about one-third of the protein. This portion revealed how ZAK’s structured domains latch onto specific areas of the ribosome, initiate activation, and respond differently depending on whether ribosomes are collided or not.

What the 3D Structure Reveals About ZAK

One of the surprising details highlighted in the analysis is that more than half of ZAK appears to be intrinsically disordered, meaning it behaves like floppy spaghetti rather than forming stable shapes. Researchers think this disordered region may act like a flexible tentacle that helps ZAK reach out and detect ribosome collisions.

The structured regions of the protein, in contrast, make very specific contacts with the ribosome:

- The C-terminal end of ZAK binds to the ribosome in both normal and collided states.

- This same region also engages in collision-specific interactions with rRNA expansion segments, which project from the ribosome like small arms.

- The RIM region, located near the center of ZAK, interacts with RACK1, a ribosomal protein known for participating in cell signaling. RACK1 binding appears to be a key step in activating ZAK when ribosomes collide.

Together, these interactions form a structural bridge between two collided ribosomes, allowing ZAK to determine when translation has been disrupted and when a stress response should be triggered.

These findings also help explain why ZAK is so difficult to study: flexible, partially unstructured proteins are notoriously hard to capture in high-resolution imaging. But even this partial structure provides critical insights that weren’t available before.

Implications for Drug Development

Most drugs that target kinases bind to the active site, a region that tends to look similar across many kinases. This similarity is what often leads to unintended side effects, since drugs end up hitting more than just their intended target.

By revealing specialized structural features unique to ZAK—particularly in the regions that recognize ribosomes—this study opens the door for designing drugs that target only ZAK’s collision-sensing functions. Treatments based on these insights could help modulate stress responses in diseases where ribotoxic stress is elevated or misregulated.

The research team intends to expand their work to capture more of ZAK’s structure, understand how the full-length protein behaves during activation, and determine what ZAK does when it is not attached to collided ribosomes.

Additional Background: How Ribosome Collisions Signal Trouble

Ribosomes are typically seen as the machinery responsible for making proteins, but research over the past decade shows they also serve as sentinels of cellular health. When translation runs smoothly, ribosomes move along mRNA one after another like cars on a highway. But when something goes wrong, ribosomes stack up and collide. These collisions are now understood as early warning signals that activate stress pathways, halt faulty protein production, and trigger cellular repair processes.

The ribotoxic stress response, in which ZAK plays a central role, is one of several pathways activated by ribosome dysfunction. This response helps ensure that damaged or incomplete proteins don’t accumulate—a process especially important for preventing inflammation, neurodegeneration, and other stress-related disorders.

Additional Background: Why Studying Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Is Challenging

Scientists have long known that many regulatory proteins, including kinases, contain highly flexible or intrinsically disordered regions. These regions do not fold into stable structures and instead remain dynamic, allowing them to interact with multiple partners. While this flexibility is biologically useful, it makes structural studies much harder because traditional techniques like X-ray crystallography cannot capture floppy regions well.

Cryo-EM, the technique used in this study, has become a powerful method for visualizing such proteins because it can capture molecules in numerous conformations. Even so, obtaining a clear structure of ZAK required tremendous effort, hundreds of imaging attempts, and careful computational reconstruction.

Why This Study Represents a Meaningful Shift

Before this research, scientists knew ZAK was activated by ribosome collisions but lacked molecular details about how it recognized collisions and initiated signaling. Now, with specific structural interactions mapped, researchers have a more direct path to designing experiments, drugs, and biological models focused on stress-response regulation.

The discovery also underscores an emerging theme in cell biology: ribosomes don’t just make proteins—they help coordinate responses to stress, acting as both machinery and messengers.

Research Reference

ZAK activation at the collided ribosome

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09772-8