Ancient Hominin Fossils Show Two Early Human Ancestors Lived Side by Side in Ethiopia

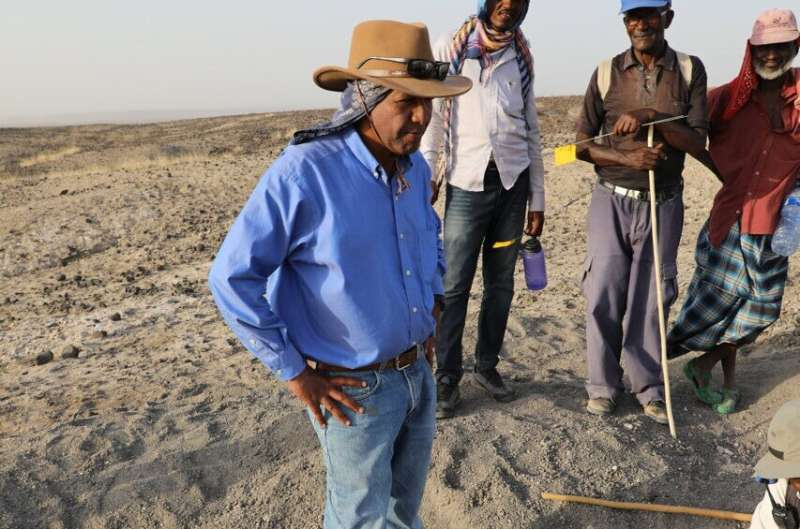

New research has shed fresh light on one of the most intriguing chapters of human evolution: the coexistence of two early hominin species in the same region more than 3 million years ago. A newly strengthened link between a mysterious fossil foot and the species Australopithecus deyiremeda confirms that this lesser-known ancient human relative lived at the same time—and in the same landscape—as the famous Australopithecus afarensis, the species to which the iconic fossil Lucy belongs. The discovery emerges from years of careful excavation, fossil association work, and lab analyses carried out at the Woranso-Mille site in Ethiopia’s Afar Rift.

The story begins in 2009, when researchers unearthed eight bones from an unusual foot within sediments dated to 3.4 million years ago. The foot—later known as the Burtele foot—was clearly different from the fully bipedal feet of A. afarensis. However, without skull or jaw remains directly associated with it, scientists refrained from assigning it to a species. Over time, more fossils, including teeth and jaw fragments, were recovered from the same stratigraphic layers. It was only after more than a decade of accumulating evidence that researchers could confidently link the Burtele foot to A. deyiremeda, a species first announced in 2015 but not originally connected to the foot.

The association matters because the Woranso-Mille site is now the only location with unambiguous evidence showing two related hominin species coexisting in both time and geography during the mid-Pliocene. These findings point to a far more diverse evolutionary landscape than once assumed.

A Closer Look at the Ancient Foot

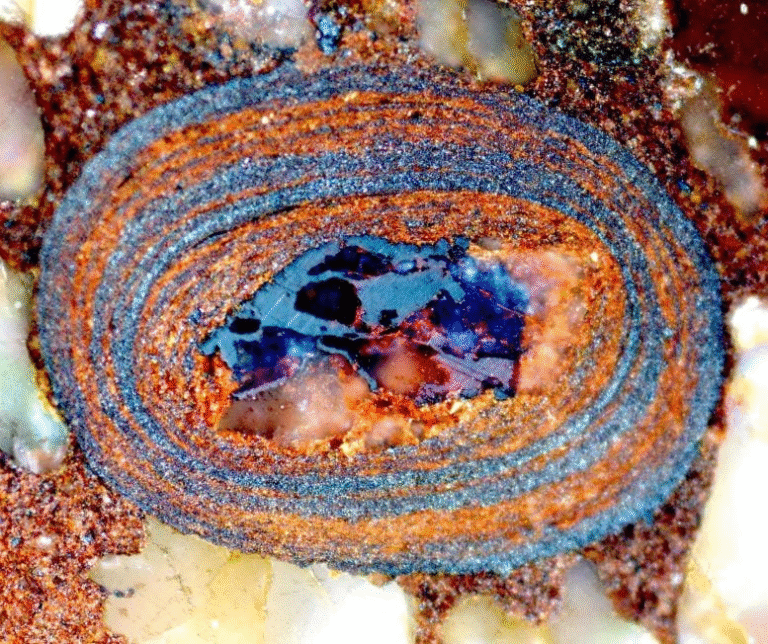

One of the standout features of the Burtele foot is its opposable big toe, a trait shared with even earlier species like Ardipithecus ramidus, which lived around 4.4 million years ago. In modern humans, the big toe is aligned with the others, forming a stable lever for upright walking. The opposable toe seen in A. deyiremeda suggests that this species retained a significant climbing ability while still walking on two legs when on the ground.

Interestingly, evidence indicates that A. deyiremeda likely pushed off the ground using its second toe, not the big toe as humans do today. This reinforces one of the study’s central points: early bipedalism came in several forms, and different hominin species experimented with different locomotor adaptations. Meanwhile, A. afarensis, inhabiting the same region at the same time, had already evolved a more humanlike, fully adducted big toe suited for committed bipedalism.

In other words, the landscape 3.4 million years ago supported more than one way of being an upright walker.

What the Teeth Reveal About Diet

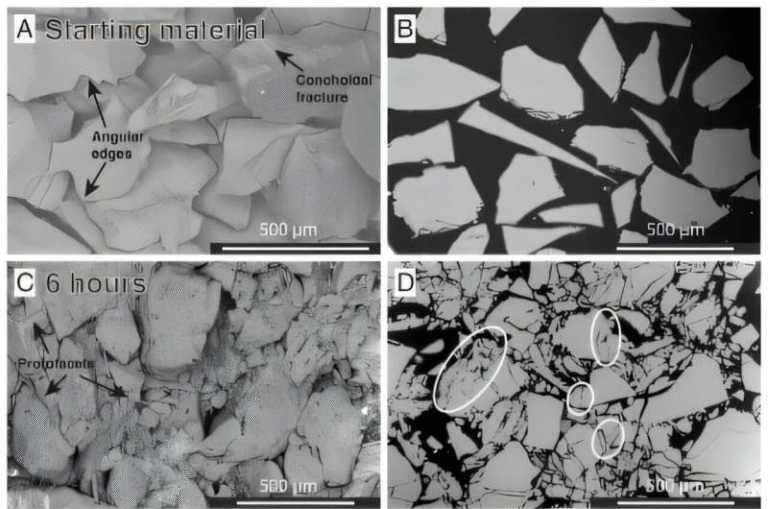

A detailed isotope analysis of eight teeth from A. deyiremeda adds another layer to the picture. The enamel preserved clear carbon signatures showing that the species ate foods based overwhelmingly on C3 plants, which typically include shrubs, trees, and woodland vegetation. This was a surprising outcome because A. afarensis—living alongside them—maintained a mixed diet of both C3 resources and C4 plants such as grasses and sedges. Even more intriguing is that A. deyiremeda’s diet closely resembled that of older hominin species like Ardipithecus ramidus and Australopithecus anamensis, suggesting a degree of dietary continuity across more than a million years.

This dietary divergence between contemporaneous species points to a strategy that likely enabled their long-term coexistence. By occupying slightly different ecological niches and relying on different food sources, the species reduced direct competition—just as many modern animal species do when sharing the same environment.

Establishing the Age and Environment

Another major component of this research involved confirming the geological ages and associations of the fossil layers. Stratigraphic work at the site, which required painstaking field mapping, sediment analysis, and layer correlation, demonstrated that the teeth, juvenile jaw, and foot remains all belonged to the same time period and environmental context.

These analyses helped narrow down the age of the fossils to around 3.4 million years, a period known for climatic fluctuations that likely influenced vegetation patterns, resource availability, and hominin adaptation. Understanding these environmental conditions allows researchers to construct more accurate models for how different species might have thrived side by side.

A Juvenile Jaw Offers Clues About Growth

Among the fossils linked to A. deyiremeda is the jaw of a juvenile individual. CT scans of the specimen revealed a complete set of baby teeth and several developing adult teeth within the jawbone. These developmental patterns allowed scientists to estimate that the child was about 4.5 years old at the time of death.

What stood out in the scans was the distinct difference in developmental timing between the front teeth (incisors) and the back molars—something commonly seen in modern apes and in other australopiths, including A. afarensis. This suggests that despite the evident diversity in locomotion, diet, and anatomy among early australopiths, their growth and development patterns were surprisingly consistent.

Why Coexistence Matters in Human Evolution

One of the most important implications of these discoveries is how they reshape our understanding of early hominin diversity. For decades, the evolutionary narrative favored a simple, almost linear progression from one species to the next. Evidence from Woranso-Mille adds to a growing body of research showing that human evolution was much more complex and that multiple species—not just one lineage—were testing different survival strategies simultaneously.

This diversity is not just academically interesting. It helps us understand how early hominins responded to environmental pressures such as climate shifts. By examining how species like A. deyiremeda and A. afarensis used different locomotor and dietary strategies to navigate shared ecosystems, researchers hope to gain insights into resilience, adaptation, and evolutionary experimentation—concepts that remain relevant as modern humans face rapid environmental change today.

Additional Context on Australopithecus and Early Human Evolution

To place these discoveries in broader context, the genus Australopithecus represents some of the earliest members of the human family to combine upright walking with varying degrees of arboreal behavior. Species in this group lived between 4.2 million and 2 million years ago. They are crucial to understanding the emergence of the genus Homo, though the exact transitions are still debated.

Some members of this group, like A. afarensis, show adaptations strongly geared toward terrestrial life. Others, like A. deyiremeda, retained traits advantageous for climbing. The coexistence of these anatomical strategies suggests that no single approach dominated early on. Instead, evolutionary pathways branched repeatedly, with multiple species exploring different combinations of mobility, diet, and habitat use.

This pluralistic view of evolution mirrors patterns seen in many other animal groups, where branching and diversity—not linear progression—drive long-term survival and innovation.

Link to the Research Paper

New Finds Shed Light on Diet and Locomotion in Australopithecus deyiremeda — https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09714-4