Vertical Hunting Helps Wild Cats Coexist in the Rainforests of Guatemala

A new study from researchers at Oregon State University and the Wildlife Conservation Society of Guatemala offers a detailed look at how four wild cat species—jaguars, pumas, ocelots, and margays—manage to live in the same dense rainforest while avoiding direct competition. The key discovery is that these species divide their hunting zones vertically, meaning some focus on prey found on the forest floor while others concentrate on animals living in the trees. This kind of vertical niche partitioning has been suspected in rainforest ecosystems, but this study is among the first to quantify it using extensive camera trap footage and DNA analysis.

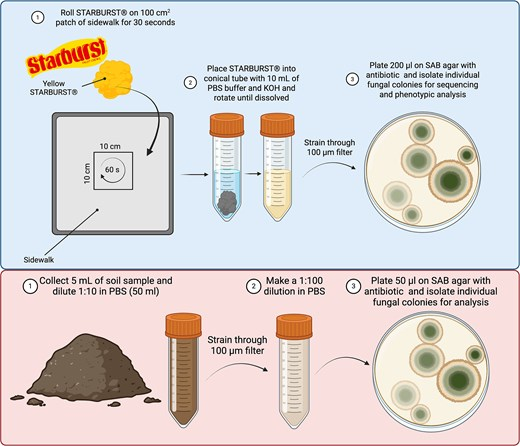

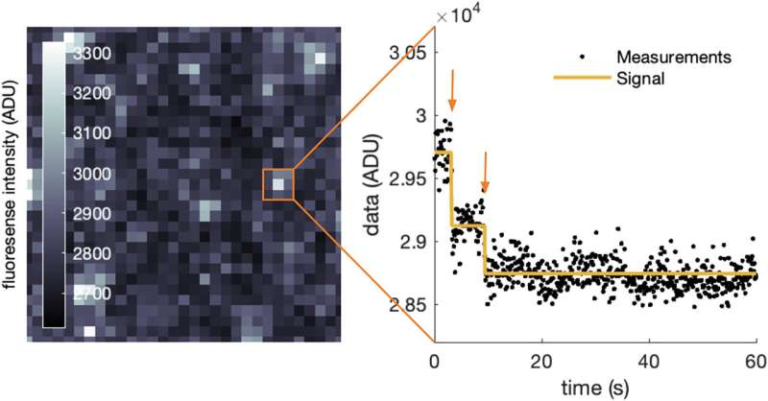

The research took place in the Maya Biosphere Reserve, a massive subtropical forest system spanning over 8,000 square miles across Guatemala, Belize, and Mexico. Field sites were extremely remote, sometimes requiring up to eight hours of travel by ATV to reach. The scientists set up 55 ground-level cameras and 30 canopy-level cameras about 40 feet above the forest floor. Alongside the camera traps, the team collected 215 scat samples, using both human field crews and two trained detection dogs—Barley and Niffler—to locate samples.

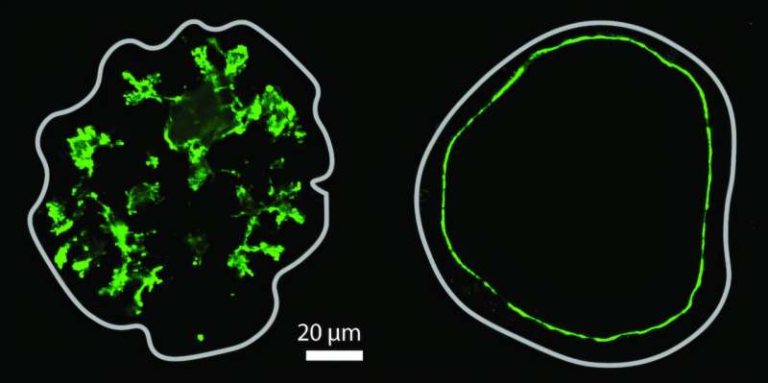

DNA metabarcoding allowed the researchers to identify the specific prey species each cat consumed. This created a detailed picture of how their diets differ, and how those differences help minimize conflict. The study confirmed that jaguars and ocelots mostly hunt on the ground, while pumas and margays show a stronger preference for tree-dwelling prey.

Among the most notable findings was the prominence of Central American spider monkeys and black howler monkeys in the diet of pumas. Monkeys contributed more than twice as much to the puma diet as traditional prey like red and gray brocket deer. This contrasts sharply with jaguars and ocelots, whose diets included almost no monkeys. In fact, jaguars were found to consume ocelots in about 10% of samples, while ocelots made up 2% of puma diets. Jaguars primarily ate peccaries and nine-banded armadillos, with some consumption of brocket deer. Ocelots focused on smaller mammals, especially large opossums, small opossums, and Gaumer’s spiky pocket mouse. Margays, being smaller and highly arboreal, fed mostly on mice, small arboreal opossums, large opossums, and rats.

The number of unique prey species detected in each cat’s diet also varied. Jaguars consumed at least 20 species, pumas 27, ocelots 25, and margays 7. These differences further emphasize how each species has carved out its own ecological role, even while occupying overlapping territories.

Even more interesting is what researchers observed about movement and habitat use. Jaguars, pumas, and ocelots were detected only at ground level throughout the study. Margays, true to their reputation as exceptional climbers, were the only species captured on both ground and canopy cameras, with 156 detections on the ground and 32 in the canopy. Although pumas consumed a surprisingly high number of arboreal animals, the study did not capture any video of pumas in the trees. This leaves open the question of how exactly they hunt monkeys and other canopy mammals. One possibility is that pumas capitalize on moments when monkeys descend to drink or forage. However, the researchers noted that monkeys did not often appear near water holes and were absent from jaguar and ocelot diets, which suggests pumas may sometimes hunt in the lower canopy, even if the behavior wasn’t captured on video.

The physical characteristics of the cats help explain these patterns. Pumas weigh less than jaguars, which may make it easier for them to navigate trees. Jaguars, known for having the strongest bite force relative to body size among big cats, are better adapted for consuming hard-shelled prey like armadillos. These biological differences influence the types of prey each species can effectively pursue.

The total camera trap data set was substantial, with 1,550 independent detections of jaguars, 1,482 of pumas, 1,378 of ocelots, and 188 of margays. Activity patterns showed similarities between jaguars and pumas, and between ocelots and margays, suggesting that while they may use similar times of day or general landscapes, their vertical separation helps ease competition.

The findings challenge long-held ecological assumptions about how large carnivores share habitat. Traditional niche theory suggests species must partition resources along axes such as space, time, or diet. In rainforests, however, vertical space adds another dimension, one that is often overlooked in carnivore studies. Most existing research on interactions between large carnivores has been done in African savannas, where vertical stratification is limited. This new study highlights the importance of considering arboreal behavior when examining predator coexistence in forest ecosystems.

These insights matter for conservation. As climate change and habitat loss continue to reshape environments, understanding how predators partition resources becomes even more critical. Interference competition, prey availability, and landscape connectivity will all influence the future survival of these species. The Maya Biosphere Reserve is already threatened by deforestation, wildfires, and human encroachment. Knowing how predators use the habitat at multiple vertical levels can guide conservation planning—for example, emphasizing the preservation of canopy corridors and ground-level pathways alike.

The research team included Ellen Dymit, Taal Levi, Joshua Twining, and Jennifer Allen from Oregon State University’s College of Agricultural Sciences, along with Rony Garcia-Anleu from the Wildlife Conservation Society of Guatemala. Their collaborative approach combined field ecology, genetics, and long-term monitoring to build one of the most detailed datasets on neotropical felid behavior to date.

This kind of research also highlights a broader point: rainforests host complex, layered ecosystems where every level from the forest floor to the canopy plays a role in shaping biodiversity. Wild cats, often thought of mainly as ground hunters, demonstrate just how adaptive and versatile predators can be. Understanding these adaptations enriches our broader understanding of rainforest ecology and the intricate webs of interaction that support wildlife communities.

Additional Context on Neotropical Wild Cats

To give readers a fuller understanding of the species involved, here’s a bit more background:

Jaguars are the largest cats in the Americas and are known for their powerful bite. They are primarily ambush predators and often hunt near water.

Pumas (also called cougars or mountain lions) have one of the widest ranges of any mammal in the Western Hemisphere. They are adaptable, solitary hunters capable of taking down a wide variety of prey.

Ocelots are medium-sized spotted cats known for their stealth and versatility. They thrive in dense forests and often hunt at night.

Margays are among the most arboreal wild cat species in the world. They can rotate their ankles to climb down trees headfirst and are known for chasing prey through branches with remarkable agility.

Understanding these species’ natural histories helps explain why vertical stratification works so well as a coexistence strategy.

Research Paper Link:

https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.70173