New Radar Evidence Suggests the Bright Signals Under Mars’ South Pole May Not Be Liquid Water

For several years, one of the most intriguing questions in planetary science has been whether liquid water still exists on present-day Mars, hidden beneath thick layers of ice. A new study now adds an important twist to that story. Fresh radar observations suggest that a highly reflective region beneath Mars’ south polar ice cap—once thought to be a strong candidate for subglacial liquid water—may have a much drier and less dramatic explanation.

This new research doesn’t erase Mars’ watery past, but it does significantly reshape how scientists interpret one of the most talked-about pieces of modern Martian evidence.

Why Scientists Thought There Might Be Liquid Water Under the Ice

Mars was not always the cold, arid world we see today. Geological features such as ancient river valleys, lakebeds, and minerals formed in water clearly show that liquid water once flowed freely across the planet’s surface. However, today’s Mars has an extremely thin atmosphere and frigid temperatures, making stable liquid water on the surface almost impossible.

That’s why attention turned underground.

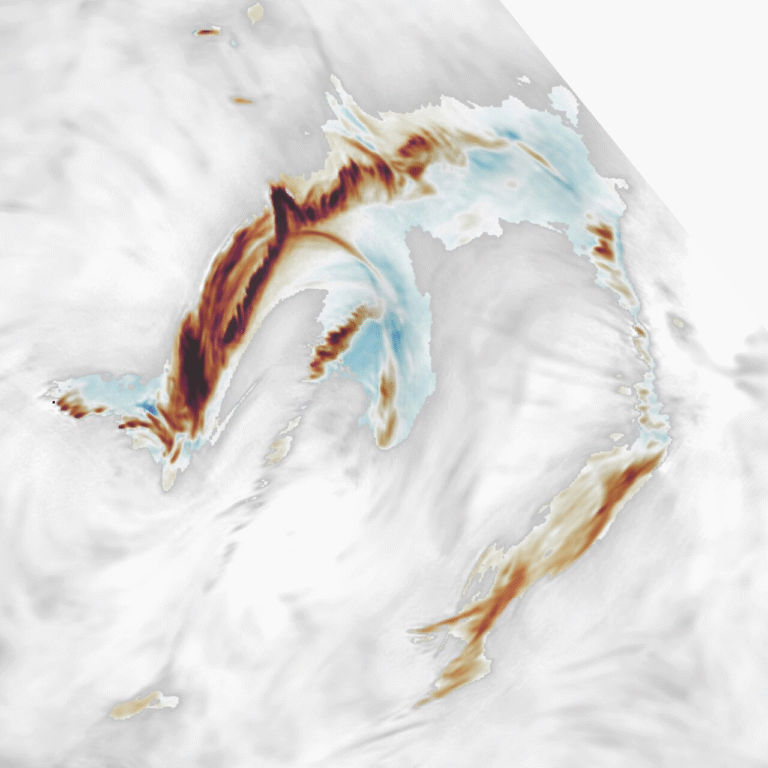

In 2018, scientists analyzing data from the Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS) instrument aboard ESA’s Mars Express spacecraft reported something remarkable. MARSIS detected strong radar reflections from a region roughly 20 kilometers wide at the base of the southern polar ice cap. On Earth, similar radar signatures are often linked to liquid water beneath glaciers, such as subglacial lakes in Antarctica.

The implication was exciting. If liquid water really existed beneath the ice, it could have major consequences for Martian habitability, both past and potentially present.

The Big Problem With Liquid Water on Modern Mars

Despite the excitement, scientists were cautious from the start. Maintaining liquid water under Mars’ south pole would be extremely challenging.

Temperatures at the base of the ice cap are expected to be far below freezing. To keep water liquid, Mars would likely need either extremely salty brines, which can remain liquid at much lower temperatures, or localized geothermal or volcanic heat beneath the ice. Neither explanation has strong supporting evidence in that region.

Because of these challenges, researchers began exploring alternative, “dry” explanations for the bright radar reflections. Possibilities included layers of carbon dioxide ice, mixtures of water ice and salty ice, or even clay-rich materials that could reflect radar signals strongly without involving liquid water.

Enter SHARAD and a New Way to Look Deeper

Mars has another radar instrument in orbit: SHARAD (Shallow Radar) aboard NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. SHARAD operates at higher frequencies than MARSIS, which gives it better resolution but usually less penetration depth.

For a long time, that limitation meant SHARAD simply couldn’t see deep enough to reach the base of the south polar ice cap. As a result, scientists couldn’t directly compare SHARAD data with the original MARSIS observations.

That changed recently.

Engineers developed a new spacecraft maneuver known as a Very Large Roll (VLR). Instead of rolling the spacecraft by its usual maximum of about 28 degrees, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter can now roll by roughly 120 degrees along its flight axis. This maneuver significantly boosts SHARAD’s signal strength and allows it to probe deeper beneath the ice than before.

What the New Study Actually Found

In the new study, published in Geophysical Research Letters, planetary scientist Gareth Morgan and colleagues analyzed 91 SHARAD observations that passed over the same high-reflectivity zone identified by MARSIS.

The results were striking.

SHARAD detected a basal echo from the site only when the Very Large Roll maneuver was used, and even then, the signal was extremely weak. This stands in sharp contrast to the strong reflections seen by MARSIS.

If a substantial body of liquid water were present, scientists would expect SHARAD—especially with enhanced penetration—to detect a much stronger and clearer signal. The faint return instead suggests that liquid water is unlikely to be responsible for the bright reflections observed earlier.

A More Mundane, But Plausible Explanation

So what is causing the radar brightness?

According to the researchers, the most likely explanation is a localized region of unusually smooth ground beneath the ice. Smooth interfaces between ice and underlying material can reflect radar waves efficiently, particularly at the lower frequencies used by MARSIS.

In other words, MARSIS may have been detecting a strong contrast in physical properties, not a pool of liquid water. SHARAD’s higher-frequency perspective, combined with the weak signal it recorded, supports this interpretation.

The team emphasizes that further research is needed to fully reconcile the differences between the two radar systems, but the new evidence strongly favors a dry geological explanation over a watery one.

Why This Doesn’t Mean Mars Is “Dry” in the Big Picture

While this finding may disappoint those hoping for hidden lakes on Mars, it doesn’t diminish the planet’s broader scientific importance.

Mars still holds vast amounts of frozen water, especially in its polar caps and subsurface ice deposits. Evidence for ancient oceans, lakes, and rivers remains robust, and other regions—particularly deep underground—could still host salty liquid brines, at least temporarily.

What this study really highlights is how complex planetary radar interpretation can be. Different instruments, frequencies, and viewing geometries can produce very different results, and extraordinary claims require careful cross-checking.

How Radar Helps Scientists Explore Other Worlds

Radar instruments like MARSIS and SHARAD work by sending radio waves toward a planet’s surface and measuring the echoes that bounce back. Variations in density, composition, roughness, and layering all affect how radar signals behave.

Lower-frequency radar can penetrate deeper but provides less detail, while higher-frequency radar offers sharper images at shallower depths. Using both together—and developing new techniques like the Very Large Roll maneuver—gives scientists a more complete picture of what lies beneath the surface.

This approach isn’t limited to Mars. Radar sounding is also used to study icy moons like Europa and Enceladus, where subsurface oceans are a major focus of astrobiology research.

What Comes Next for This Mystery

The authors of the study stress that this isn’t the final word on the south polar reflections. Continued radar observations, improved modeling, and future missions may further clarify the nature of the subsurface layers.

For now, though, the most exciting conclusion is also the most cautious one: the bright radar signals beneath Mars’ south pole are probably not liquid water, but rather a reminder of how easily nature can mimic familiar patterns in unfamiliar environments.

Science advances not just through discovery, but through refinement and reassessment, and this study is a perfect example of that process in action.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1029/2025GL118537