Accessible Urban Parks Are Linked to Higher Daily Physical Activity Across U.S. Cities

Urban parks have long been praised for their beauty, mental health benefits, and ecological value. But a growing question in public health has been whether these green spaces actually help people move more in their everyday lives. A large new study suggests that they do — but only when people can easily reach them. According to fresh research analyzing real-world wearable data, park accessibility, not just the presence of greenery, plays a major role in how physically active city residents are across the United States.

Why Physical Activity and Cities Matter Right Now

The study arrives at a critical moment. Public health experts increasingly describe physical inactivity as a global pandemic, with the United States facing particularly stark challenges. A large portion of the population fails to meet recommended daily activity levels, increasing the risk of chronic conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, and obesity. Since most Americans live in cities, understanding how urban design influences daily movement is more important than ever.

Nature has often been linked to healthier lifestyles, but much of the existing evidence has relied on self-reported surveys, short-term studies, or data from just a handful of cities. This new research takes a much broader and more data-driven approach, offering one of the most detailed looks yet at how urban green space and physical activity are connected.

A Large-Scale Study Using Wearable Data

Researchers from the Stanford-based Natural Capital Project (NatCap) analyzed data from 7,013 adults living in 53 U.S. metropolitan areas. The participants voluntarily shared information from their Fitbit wearable devices as part of the All of Us Research Program, a national health initiative designed to improve medical research through diverse, long-term data collection.

What makes this study stand out is its scale and duration. Instead of relying on short snapshots of behavior, the researchers examined three years of daily step counts and activity intensity data. This allowed them to track consistent patterns in movement over time while accounting for differences between individuals and cities.

To ensure accuracy, the research team used advanced statistical models that controlled for a wide range of factors, including weather conditions, population density, air quality, and city walkability. This approach helped isolate the specific role that urban nature plays in shaping physical activity.

Greenness vs. Accessibility: An Important Distinction

One of the most important findings of the study is that not all green space has the same impact on physical activity. The researchers distinguished between two key concepts:

- Overall greenness, measured using satellite imagery that captures vegetation such as trees, gardens, and forests

- Park accessibility, which includes whether parks exist, how close they are to where people live, how easy they are to reach on foot, and how well they are connected to surrounding neighborhoods

The results were clear. General greenness alone was not associated with higher physical activity levels. In other words, simply living in a city with lots of trees or vegetation does not automatically make people more active.

In contrast, park accessibility showed a strong and consistent relationship with movement. The easier it was for residents to walk to a nearby park, the more active they tended to be.

How Much Difference Does Access Make?

The researchers quantified this relationship in a practical way. They found that a 10 percent increase in park accessibility was linked to an average increase of about 107 additional steps per day per person.

While 107 steps may not sound dramatic on its own, the impact becomes significant when scaled across entire populations and over long periods of time. Small daily increases in movement can add up to meaningful improvements in cardiovascular health, mobility, and overall well-being.

Climate Plays a Major Role

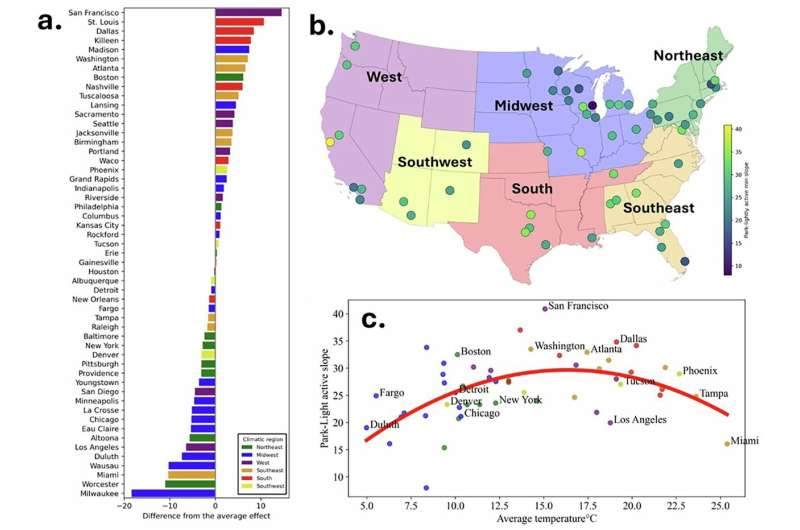

The study also revealed that where a city is located matters. The link between park accessibility and physical activity was strongest in western and southern U.S. cities. Researchers believe this may be influenced by regional differences in climate, culture, and outdoor habits.

Temperature, in particular, had a noticeable effect. In cities with mild weather, park accessibility had a much stronger impact on daily step counts. In places that experience extreme heat or cold, the benefits were still present but less pronounced, likely because harsh conditions discourage outdoor activity regardless of park access.

Other environmental factors, such as air quality, rainfall, and walkability, were also included in the analysis. Cities with cleaner air and more walkable streets generally showed higher activity levels.

Who Benefits the Most From Accessible Parks?

One of the most important contributions of this research is its focus on equity. Because the dataset spanned multiple years and included thousands of participants, the researchers were able to examine how different groups responded to improved park access.

The findings were striking. Non-white residents, older adults, and people who were less active at the start of the study experienced the largest increases in physical activity when parks were easier to reach. This supports the idea of an equigenic effect, where improvements in environmental conditions can reduce health disparities by benefiting more vulnerable populations the most.

In practical terms, this means that improving park access in underserved neighborhoods could have an outsized impact on public health and help narrow long-standing inequalities in physical activity and health outcomes.

Rethinking Urban Planning and Public Health

The study challenges a common assumption in city planning: that simply adding more green space is enough. Instead, it suggests that how parks are integrated into the urban landscape matters just as much as how many there are.

Cities may not need to focus solely on building new parks. Improving walkability, removing physical barriers such as highways or busy roads, and creating better connections between neighborhoods and existing parks can also encourage residents to move more.

Examples of such interventions include pedestrian overpasses, safer crossings, expanded sidewalks, and green corridors that link residential areas to nearby parks. These changes can make parks feel like a natural part of daily life rather than distant destinations.

Why Wearable Data Changes the Conversation

Another important aspect of this study is its use of objective wearable data rather than self-reported activity. Wearable devices provide consistent, day-by-day measurements that reduce common reporting biases and offer a clearer picture of how people actually move.

The researchers did note some limitations. Participants in the dataset tended to be older, more affluent, and more active than the U.S. average, which means the findings may not fully represent all populations. Still, the size and duration of the dataset make the results highly valuable for understanding broad trends.

Looking Ahead

The research team sees several promising directions for future studies. Tracking how changes in park accessibility over time affect activity levels could help cities evaluate the impact of specific interventions. Incorporating GPS data may also allow researchers to measure actual park usage rather than relying solely on proximity.

Recruiting more diverse participants will be another key step in strengthening the evidence base and ensuring that urban planning decisions benefit everyone.

The Bigger Picture

At its core, this study reinforces a simple but powerful idea: nature supports human health best when it is accessible. Parks that people can easily reach on foot are more than just scenic amenities. They are active tools for improving public health, encouraging movement, and promoting equity in cities across the country.

By focusing on access rather than aesthetics alone, urban planners and policymakers have an opportunity to make cities healthier, more inclusive, and better suited to everyday life.

Research paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s44360-025-00011-y