A Genetic Variant May Explain Why Some Children With Myocarditis Go On to Develop Heart Failure

A new study published in the journal Circulation: Heart Failure is shedding important light on a long-standing medical mystery: why some children with myocarditis recover, while others rapidly progress to heart failure, a life-threatening condition. According to researchers, the answer may lie in hidden genetic variants that weaken the heart long before any infection occurs.

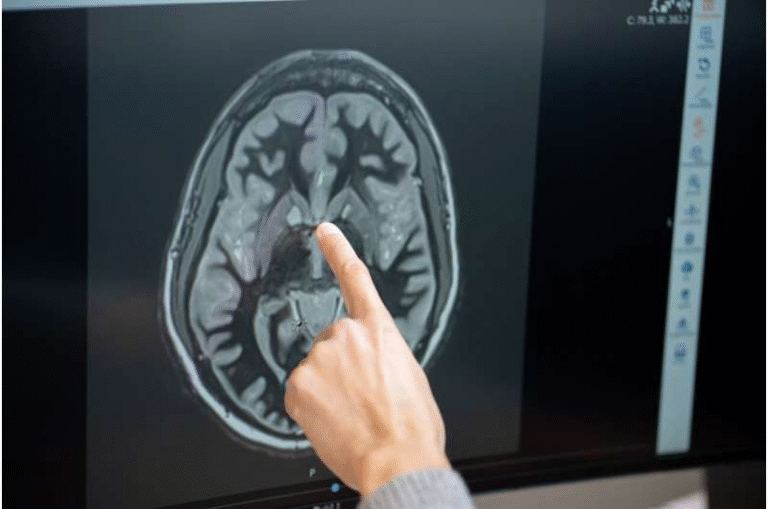

Myocarditis is an inflammation of the heart muscle, most often triggered by viral infections. While it is considered rare, it has been identified in U.S. federal databases as the leading cause of sudden death in people under 20 years of age. Despite this serious risk, most children who get common viral infections never develop myocarditis, and even fewer go on to develop heart failure. This uneven pattern has puzzled doctors for decades.

The new research strongly suggests that genetics play a critical role in determining which children are most vulnerable.

What the Study Found

The study analyzed data from the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry (PCMR), a long-running network of pediatric heart centers across the United States and Canada. Researchers compared three groups of children:

- Children who developed dilated cardiomyopathy after myocarditis

- Children who had myocarditis but did not develop cardiomyopathy

- Heart-healthy control children

The results were striking. Among children who developed dilated cardiomyopathy following myocarditis, 34.4% carried pathogenic genetic variants linked to cardiomyopathy. In contrast, only 6.3% of the control group had these same genetic variants. The difference was statistically significant and difficult to ignore.

Dilated cardiomyopathy is a condition in which the heart’s main pumping chamber stretches, becomes thinner, and loses its ability to pump blood efficiently. Over time, this can lead to heart failure, where the heart can no longer supply enough oxygenated blood to meet the body’s needs.

Why These Genetic Variants Matter

The presence of cardiomyopathy-associated genetic variants appears to reduce what doctors call cardiac reserve. Cardiac reserve is the heart’s ability to respond to stress, such as infection, fever, or inflammation. A heart with reduced reserve may function normally under everyday conditions, but it has far less capacity to handle sudden challenges.

In practical terms, this means a child with a hidden cardiomyopathy gene variant may seem perfectly healthy—until a viral infection triggers myocarditis. When that happens, the heart is already at a disadvantage.

Researchers describe this as a “double hit” mechanism:

- The first hit is being born with a pathological genetic mutation that weakens the heart’s structure or function.

- The second hit is an infection that inflames the heart muscle, leading to myocarditis.

Together, these two factors significantly increase the risk of heart failure, recurrent myocarditis episodes, and even sudden cardiac death.

A Shift in How Doctors May Approach Myocarditis

One of the most important implications of this study is its call for routine genetic testing in children who present with myocarditis, especially those who develop signs of cardiomyopathy or heart failure.

Currently, genetic testing for cardiomyopathy-causing variants is not commonly performed when children arrive at hospitals with new-onset heart failure. The study’s authors argue that this practice needs to change.

Identifying pathogenic gene variants early could help doctors:

- Recognize children at higher risk of severe outcomes

- Monitor them more closely over time

- Make informed decisions about aggressive interventions

In some cases, children with these mutations may be candidates for implantable cardiac defibrillators, devices that can prevent sudden death by correcting dangerous heart rhythms.

The Role of the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry

The Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry played a central role in this research. The registry has collected detailed clinical and genetic data on children with cardiomyopathy for decades, making it one of the most valuable resources for understanding rare pediatric heart diseases.

Children in the myocarditis-with-cardiomyopathy group were drawn directly from this registry, allowing researchers to compare them against carefully selected control groups. This large, well-characterized dataset helped strengthen the reliability of the findings.

Genetics and the Immune System Connection

This study builds on earlier research showing that genetics can influence how children respond to common infections. Previous work involving data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control found that some families carry genetic mutations that impair the immune system’s ability to fight everyday viruses.

In those cases, children may be more likely to experience severe viral infections that spread beyond typical sites like the respiratory tract and reach the heart muscle. When combined with cardiomyopathy-related genetic variants, the risk becomes even higher.

This growing body of evidence suggests that myocarditis is often not just a random complication of infection, but the result of an interaction between infection and inherited vulnerability.

Why Most Children Don’t Get Myocarditis

An important point highlighted by the researchers is how common infections are in childhood. During the first year of life alone, infants experience an average of seven infections. Yet myocarditis remains rare, and heart failure even rarer.

This discrepancy strongly supports the idea that infection alone is not enough to cause severe cardiac outcomes. Genetic predisposition helps explain why only a small subset of children experience catastrophic heart involvement.

Broader Implications for Pediatric Heart Care

The findings could influence how pediatric cardiologists think about myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, and sudden cardiac death risk. Instead of viewing myocarditis purely as an acute inflammatory condition, doctors may increasingly see it as a trigger that reveals underlying genetic heart disease.

This shift could lead to:

- Earlier diagnoses of inherited cardiomyopathies

- Family screening to identify at-risk relatives

- Long-term follow-up plans tailored to genetic risk

Ultimately, the goal is prevention—identifying children who appear healthy but carry genetic variants that put them in danger when illness strikes.

Recognition and Research Leadership

The study received significant recognition within the medical community. It was named a Top Pediatric Cardiology Research project when presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

The research was led by pediatric cardiologists and geneticists from multiple institutions. Genetic analyses were overseen by experts in medical and molecular genetics, highlighting the interdisciplinary nature of modern cardiovascular research.

What This Means Going Forward

While myocarditis remains unpredictable, this research brings clarity to why outcomes differ so dramatically among children. Genetics may not be the sole factor, but it is increasingly clear that it is a major piece of the puzzle.

As genetic testing becomes more accessible and integrated into pediatric care, studies like this one could help transform how doctors identify risk, guide treatment, and ultimately save young lives.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1161/circheartfailure.125.013104