Scientists Discover How Singing Mice Use the Same Brain Circuit for Songs and Squeaks

Not all mice communicate in the same way. While most mice are known for their familiar high-pitched squeaks, a rare species called Alston’s singing mice (Scotinomys teguina) takes vocal communication to a whole new level. These mice don’t just squeak — they produce loud, rhythmic songs that are clearly audible to the human ear. A new neuroscience study now explains how these songs are produced and, more importantly, what’s happening inside the brain to make them possible.

Researchers from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) have uncovered that both the dramatic songs and the quieter ultrasonic calls of these mice are controlled by the same conserved brain region, offering fresh insights into how complex vocal behaviors may evolve — including those related to human speech.

A Rare Mouse That Truly Sings

Alston’s singing mice are native to the cloud forests of Costa Rica, where dense vegetation and fog make long-distance communication difficult. To adapt, these mice evolved the ability to sing long, loud, and structured vocal sequences that can travel far through their environment. Unlike typical mouse vocalizations, these songs are audible without special equipment, making them unique among rodents.

Interestingly, singing mice don’t abandon traditional mouse communication altogether. They still produce ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs) — extremely high-frequency sounds used for short-range interactions. This dual communication system raised a major scientific question: How does the brain produce two very different types of vocalizations?

Studying Vocal Behavior in Detail

To answer that question, the research team first needed a reliable way to measure and classify mouse sounds. They developed a behavioral testing system known as PARId, which allowed them to carefully analyze when, why, and how different sounds were produced.

Using this system, scientists confirmed that singing mice rely on:

- Long, loud, rhythmic songs for long-distance communication

- Ultrasonic vocalizations for close-range social interaction

This confirmed that singing mice switch vocal strategies depending on context, rather than relying on a single sound type.

How Are the Sounds Physically Produced?

One surprising part of the study involved figuring out how the sounds are generated in the body. The researchers tested whether singing mice produce sound by vibrating their vocal cords, similar to humans, or through another mechanism.

To do this, they exposed the mice to helium, a classic experiment known to change sound pitch. If vocal cords were responsible, the pitch would stay the same. Instead, both the songs and ultrasonic calls increased in pitch, showing conclusively that the sounds are produced using a whistle-based mechanism, where air movement — not vocal cord vibration — creates sound.

This finding demonstrated that both songs and USVs share the same sound-production mechanism, despite sounding completely different.

One Brain Region Controls It All

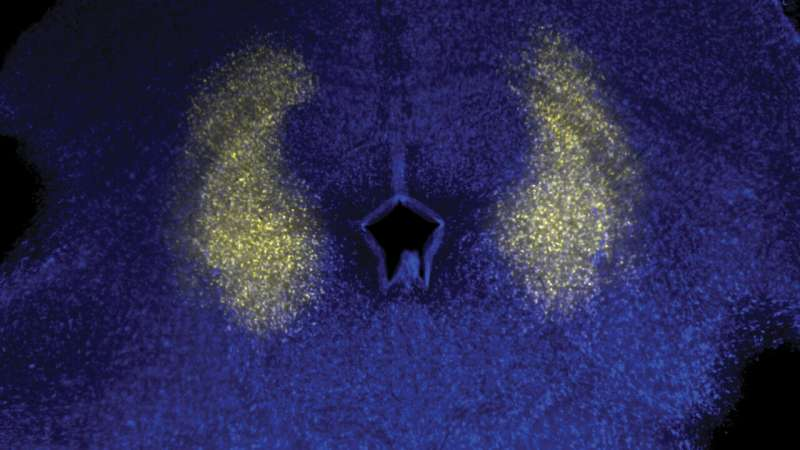

The most significant discovery came when researchers examined the mice’s brains. Using specialized viruses, they targeted and manipulated specific neural regions involved in vocal control. The results were striking.

Both singing and ultrasonic vocalizations originate from the caudolateral periaqueductal gray (clPAG), a region located in the midbrain. This same region is used by ordinary laboratory mice for everyday communication.

In other words, singing mice did not evolve an entirely new brain structure to sing. Instead, they repurposed an existing neural circuit, expanding its function to support more complex vocal behavior.

This finding challenges the idea that new behaviors require entirely new brain regions. Instead, it supports the idea that evolution often works by modifying and fine-tuning existing neural pathways.

What Happens When the Circuit Is Disrupted?

To better understand how this circuit works, the researchers partially silenced the clPAG. When they did, the mice didn’t stop singing entirely — but their songs became shorter, quieter, and less structured.

This showed that the clPAG plays a crucial role in controlling:

- Song duration

- Loudness

- Rhythmic structure

The same circuit also contributes to natural variation in vocal behavior, including differences between male and female mice.

Why This Matters Beyond Mice

While this research may seem highly specific, its implications extend far beyond rodents. Vocal communication is a fundamental social behavior across mammals, including humans. Understanding how a single conserved brain circuit can produce both simple and complex vocalizations helps scientists better understand:

- Speech production

- Social communication

- Neurological disorders affecting speech

Conditions such as stroke-induced aphasia, where individuals lose the ability to speak, and profound autism, where communication can be severely affected, may involve disruptions in similar brain pathways. Insights from singing mice could eventually help guide new research into diagnosis or treatment strategies.

What Makes Singing Mice a Powerful Research Model?

Singing mice offer a rare opportunity for neuroscience research because:

- Their brains are similar in structure to standard lab mice

- Their vocal behavior is far more complex

- Their songs are easy to record and analyze

This combination allows researchers to study how complex behaviors emerge without the confounding factor of dramatically different brain anatomy.

A Broader Look at Vocal Communication in Animals

Vocal communication exists across the animal kingdom, from birds and frogs to whales and primates. Many species rely on specialized brain circuits to produce sound, but the singing mouse study highlights an important principle: complex communication doesn’t always require new neural machinery.

Instead, evolution can take a basic system and gradually expand its capabilities. This principle may apply not just to vocal behavior, but to learning, memory, and social interaction as well.

Looking Ahead

The researchers now aim to identify what makes singing mice different at a finer level. If the brain region is the same, what changes allow it to produce longer and more complex songs? Are there differences in connectivity, timing, or chemical signaling within the circuit?

By answering these questions, scientists hope to gain deeper insight into how brains evolve new abilities — and how those abilities sometimes fail.

Research Paper:

https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(25)01379-X