Scientists Link Tenascin-C Protein to Muscle Stem Cell Health and New Possibilities for Treating Age-Related Muscle Loss

As people grow older, one of the most noticeable physical changes is a gradual loss of muscle strength and reliability. Tasks that once felt automatic—standing up from a chair, climbing stairs, or even getting out of bed—can become difficult and risky. This decline is often driven by sarcopenia, a condition marked by reduced muscle mass and function that affects millions of older adults worldwide. Now, new research from scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute sheds light on a key biological factor behind this process and points toward possible future treatments.

The study, published in the journal Communications Biology, focuses on a protein called tenascin-C (TnC) and its role in maintaining healthy muscle stem cells, which are essential for muscle repair and regeneration. The findings reveal how declining levels of this protein with age may directly contribute to weaker muscles and slower recovery after injury.

Why Muscle Stem Cells Matter for Aging Muscles

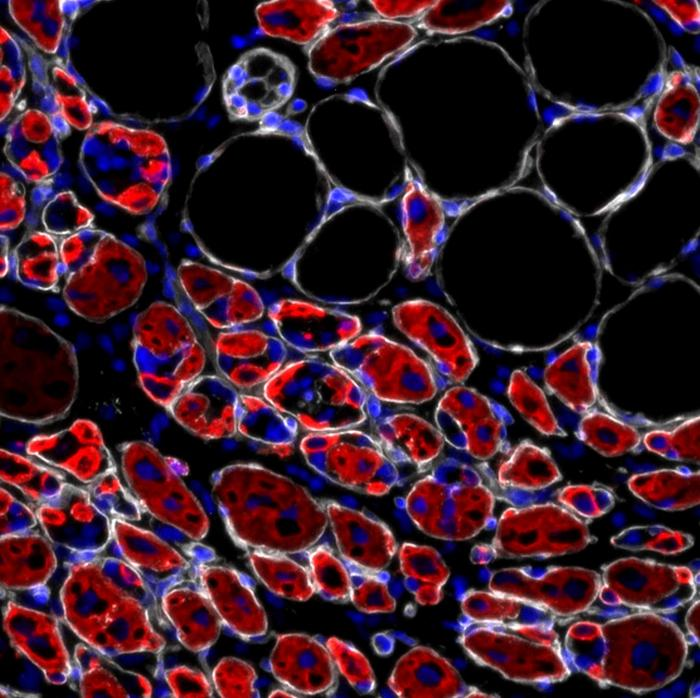

Skeletal muscle has a remarkable ability to repair itself. When muscle fibers are damaged—through injury, daily wear and tear, or exercise—specialized cells called muscle stem cells, also known as satellite cells, step in. These cells can activate, multiply, and either repair damaged fibers or replenish the stem cell pool for future needs.

As people age, this repair system becomes less efficient. Muscle stem cells decline in both number and function, which limits the body’s ability to rebuild muscle tissue. This loss is a major contributor to sarcopenia and is strongly linked to increased hospitalizations, falls, fractures, and reduced independence in older adults. Understanding what controls muscle stem cell health is therefore a critical step toward improving quality of life during aging.

The Discovery of Tenascin-C’s Role

The research team, led by Alessandra Sacco, focused on the extracellular matrix, the gel-like network that surrounds and supports cells inside tissues. While often overlooked, this environment plays a powerful role in regulating how cells behave.

Earlier work by the team showed that muscle regeneration in adults often reactivates biological pathways that were active during embryonic development. During this prenatal stage, muscles are rapidly forming, and certain proteins are highly expressed to support that growth. One of those proteins is tenascin-C.

Tenascin-C is normally present at very low levels in healthy adult muscle. However, it rises sharply after muscle injury, suggesting it helps switch on the repair process. The researchers wanted to understand exactly how TnC affects muscle stem cells and whether aging interferes with this relationship.

What Happens When Tenascin-C Is Missing

To investigate, the team studied genetically modified mice that lacked tenascin-C. The results were striking. Compared to normal mice, those without TnC had fewer muscle stem cells. Even more importantly, the remaining stem cells were less capable of renewing themselves and maintaining a stable population.

This deficit had real consequences. When muscles were injured, mice lacking TnC showed significant defects in muscle repair. Their muscles regenerated more slowly and less effectively, closely resembling the impaired regeneration typically seen in aging tissue. In essence, the absence of TnC caused muscles to behave as if they were prematurely aged.

Where Tenascin-C Comes From and How It Works

The researchers next explored the source of tenascin-C and how it communicates with muscle stem cells. They discovered that TnC is produced by support cells known as fibroadipogenic progenitors (FAPs). These cells are already known to play a crucial role in coordinating muscle regeneration by interacting with stem cells during repair.

TnC doesn’t act randomly. The team identified a specific receptor on muscle stem cells called Annexin A2. When TnC binds to this receptor, it sends signals that help stem cells survive, self-renew, and migrate to sites of muscle injury. This precise signaling pathway highlights how multiple cell types work together, much like instruments in an orchestra, to restore damaged muscle tissue.

Aging Reduces Tenascin-C and Slows Muscle Repair

One of the most important parts of the study focused on aging itself. When the researchers compared young and aged mice, they found that older muscles contained much lower levels of tenascin-C. This reduction was associated with muscle stem cells that struggled to move toward injury sites and participate effectively in repair.

Crucially, the scientists showed that this defect was not permanent. When aged muscle stem cells were treated with tenascin-C, their ability to migrate and function improved. This suggests that restoring TnC signaling could potentially reverse some aspects of age-related muscle decline.

Why This Matters for Sarcopenia and Frailty

Sarcopenia is more than just muscle weakness. It is a major driver of frailty, loss of independence, and serious injuries in older adults. The discovery that tenascin-C levels naturally decline with age provides a clear biological explanation for why muscle regeneration becomes less efficient over time.

The study also shows that mice lacking TnC display a premature aging phenotype, strengthening the idea that this protein is a key guardian of muscle health. By identifying TnC and its receptor Annexin A2 as central players, researchers now have specific molecular targets to explore for future therapies.

Challenges in Turning This Discovery Into a Treatment

While the findings are promising, translating them into a medical treatment is not straightforward. Tenascin-C is a large extracellular protein, which makes it difficult to deliver effectively through standard methods like pills or injections. Simply adding the protein to the body is not an easy solution.

Researchers are now working on alternative strategies, such as finding ways to mimic TnC’s effects, stimulate its production locally in muscle tissue, or target the Annexin A2 signaling pathway directly. These approaches could eventually lead to therapies that help preserve muscle strength and reduce frailty in aging populations.

Extra Context: The Role of the Extracellular Matrix in Muscle Health

This study also highlights a broader and increasingly important concept in biology: cells do not operate in isolation. The extracellular matrix provides structural support, but it also delivers signals that influence cell behavior, stem cell maintenance, and tissue regeneration.

In muscle, changes to this microenvironment can dramatically alter how stem cells respond to injury. Aging is known to affect the composition of the extracellular matrix, making it stiffer and less supportive. The decline of tenascin-C appears to be one piece of this larger puzzle, reinforcing the idea that restoring a youthful cellular environment could be just as important as targeting the cells themselves.

Looking Ahead

Advances in medicine have significantly extended human lifespan, but extending health span—the number of years people remain active and independent—remains a major challenge. By uncovering how tenascin-C supports muscle stem cells and how its loss contributes to age-related muscle decline, this research offers a clear direction for future work.

While practical treatments are still years away, the study represents an important step toward addressing muscle loss, frailty, falls, and fractures in older adults. Maintaining strong, resilient muscles may one day be possible not just through exercise and nutrition, but also through therapies that restore the body’s own regenerative signals.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-025-09189-z