Scientists Map How Psilocybin Rewires Brain Circuits Linked to Depression

A new study has taken a major step toward explaining how psilocybin physically reshapes the brain, offering fresh insight into why this psychedelic compound can have long-lasting effects on depression after just a single dose. Led by researchers at Cornell University, the work combines cutting-edge neuroscience tools with an unusual biological helper—the rabies virus—to trace how psilocybin alters large-scale brain connectivity.

The findings, published on December 5, 2025, in the journal Cell, reveal that psilocybin weakens certain brain feedback loops associated with negative thinking while strengthening connections that link perception to action. Together, these changes may help explain why people with depression often report relief that lasts weeks or even months following treatment.

Mapping the Brain After Psilocybin

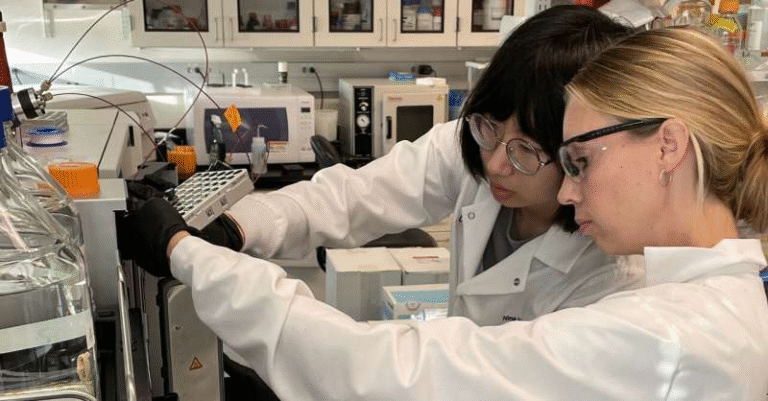

The research was led by postdoctoral researcher Quan Jiang, with Alex Kwan, a professor of biomedical engineering at Cornell Engineering, serving as senior author. Kwan’s lab focuses on understanding how psychiatric drugs—such as psilocybin, ketamine, and 5-MeO-DMT—rewire neural circuits in ways that could be harnessed for therapeutic use.

Psilocybin, the psychoactive compound found in magic mushrooms, has already shown promise in clinical trials for treating depression. What has remained unclear is why its effects last so long, especially compared to traditional antidepressants that often require daily dosing.

Earlier work from Kwan’s group in 2021 demonstrated that a single dose of psilocybin triggers structural plasticity, rapidly increasing the growth of dendritic spines—tiny protrusions on neurons that form synaptic connections. That study showed new connections were forming, but not where those connections were going or how they altered broader brain networks.

This new research set out to answer that missing piece.

Using a Virus to Trace Neural Connections

Instead of relying solely on optical imaging of individual synapses, the researchers turned to a powerful biological tracing tool: a genetically engineered rabies virus developed by collaborators at the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle.

In nature, rabies spreads by jumping across synapses from neuron to neuron. Scientists have learned to modify this property so the virus can safely trace neural connections without causing disease. In this study, the virus was engineered to label connected neurons with fluorescent proteins, allowing researchers to visualize entire circuits.

The experiment unfolded in several steps:

- A single dose of psilocybin was injected into the frontal cortical pyramidal neurons of mice.

- One day later, the modified rabies virus was introduced.

- Over the course of a week, the virus spread across synapses, marking connected neurons.

- The researchers then imaged the brains and compared them to control mice that received the virus but not psilocybin.

This approach allowed the team to generate a brain-wide wiring map, revealing how psilocybin changes connectivity across multiple regions rather than just isolated areas.

Weakening Feedback Loops Linked to Rumination

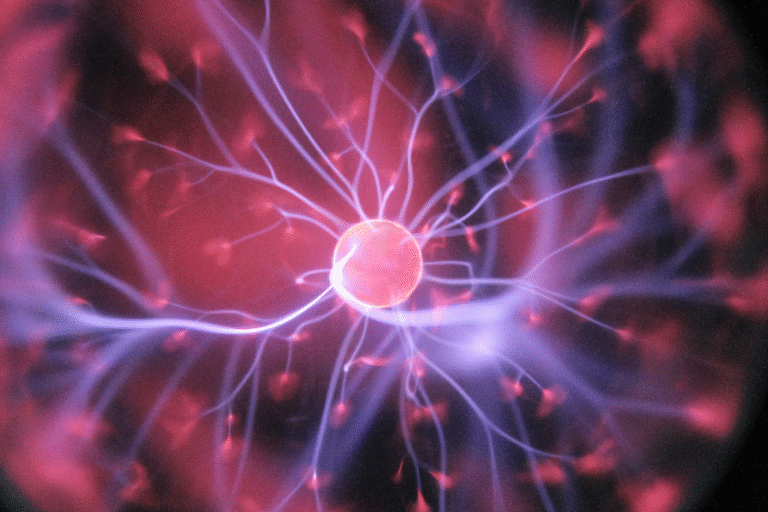

One of the most striking findings involved changes within the cortex itself. Psilocybin reduced recurrent cortico-cortical connections, which are feedback loops where signals repeatedly circulate between cortical regions.

These loops are thought to play a role in rumination, a hallmark of depression characterized by persistent, repetitive negative thoughts. When these loops are overly strong, the brain can become stuck in rigid patterns of thinking.

By weakening these feedback circuits, psilocybin may help disrupt the neural basis of rumination, making it easier for the brain to move out of negative thought cycles. This aligns well with reports from patients who describe feeling mentally “unstuck” or more flexible after psychedelic-assisted therapy.

Strengthening Links Between Perception and Action

At the same time, the study found that psilocybin strengthened connections between sensory cortical areas and subcortical regions. These pathways play a crucial role in transforming sensory information into action.

In practical terms, this enhanced wiring may help explain why psychedelic experiences often involve heightened sensory awareness and why those experiences can translate into meaningful behavioral changes afterward.

Rather than remaining trapped in internal loops of thought, the brain appears to become more engaged with incoming sensory information and more capable of responding to it.

Brain-Wide Effects, Not Local Tweaks

Initially, the researchers expected psilocybin to affect just a few specific brain regions. Instead, they found changes across the entire brain.

This discovery highlights that psilocybin does not act like a targeted switch that flips one circuit on or off. Instead, it appears to reshape large-scale networks, altering how different regions communicate with one another.

This brain-wide rewiring represents a scale of plasticity that the researchers had not previously examined and suggests that the drug’s therapeutic effects emerge from coordinated changes across many systems at once.

Activity-Dependent Rewiring

Another key insight from the study is that psilocybin’s effects depend on neural activity levels. Regions that were more active during treatment were more likely to undergo rewiring.

To test this idea, the team experimentally altered the activity of specific brain regions and observed how that changed the way psilocybin reshaped circuits. The results showed that manipulating neural activity could steer where plasticity occurred.

This finding opens the door to future therapies that combine psilocybin with other interventions—such as behavioral therapy or brain stimulation—to enhance beneficial changes while avoiding unwanted ones.

Why This Matters for Depression Treatment

Traditional antidepressants primarily work by adjusting neurotransmitter levels, and their benefits often fade once the medication is stopped. Psilocybin appears to work differently by changing the structure and connectivity of neural circuits themselves.

This may explain why clinical trials have found sustained symptom relief long after the drug has left the body. Rather than temporarily boosting chemical signals, psilocybin seems to help the brain reorganize itself in ways that support healthier patterns of thought and behavior.

Broader Context: Psychedelics and Brain Plasticity

Psilocybin is part of a broader class of psychedelics that are increasingly being studied for their ability to promote neuroplasticity. Substances like ketamine have already entered clinical use for treatment-resistant depression, while others are still under investigation.

What sets this study apart is the level of anatomical detail it provides. By directly mapping how connections change across the brain, it moves the field closer to understanding not just that psychedelics work, but how they work at the circuit level.

This knowledge is essential for developing safer, more precise treatments that harness the benefits of psychedelics without unnecessary risks.

Looking Ahead

The researchers emphasize that while the study was conducted in mice, the principles uncovered may help guide future human research. Understanding which circuits are altered—and under what conditions—could help clinicians design therapies that maximize positive outcomes for people with depression and other psychiatric conditions.

As research continues, studies like this one are laying the groundwork for a new generation of mental health treatments rooted in guided brain plasticity, rather than symptom management alone.

Research Paper Reference:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.11.009