Scientists Identify a New Genetic Target That Could Change How Friedreich’s Ataxia Is Treated

Friedreich’s ataxia (FA) is a rare, inherited neurological disorder that usually appears in childhood or early adolescence and gradually worsens over time. Most patients are diagnosed between the ages of 5 and 15, and many face serious mobility issues, heart complications, and a shortened life expectancy, often living only into their 30s or 40s. Despite decades of research, there is still no broadly effective, disease-modifying treatment that works for all patients.

Now, researchers from Mass General Brigham and the Broad Institute have uncovered a major genetic insight that could open the door to an entirely new treatment strategy. Their work, published in Nature, identifies a genetic “modifier” that helps cells function even when the key disease-causing protein is missing. This discovery shifts the focus away from trying to replace the missing protein itself and instead points toward a more drug-friendly target.

Understanding the Root Cause of Friedreich’s Ataxia

At the heart of Friedreich’s ataxia is the loss of a mitochondrial protein called frataxin. Frataxin plays a critical role in the production of iron–sulfur clusters, small molecular structures that are essential for energy generation, DNA repair, and many other cellular processes.

When frataxin levels are too low, mitochondria struggle to function properly. This leads to widespread cellular stress, especially in energy-hungry tissues like the nervous system and heart, which explains many of the hallmark symptoms of FA, including poor coordination, muscle weakness, and cardiomyopathy.

While some therapies aim to manage symptoms or slightly slow progression, restoring mitochondrial function at a fundamental level has remained an unsolved challenge.

A Surprising Clue from Low-Oxygen Experiments

In earlier research, the lab led by Vamsi Mootha found something unexpected: exposing cells, worms, and even mice lacking frataxin to low-oxygen (hypoxic) conditions partially restored cellular function. While hypoxia itself is not a practical long-term therapy, it served as a valuable experimental tool.

Instead of trying to turn hypoxia into a treatment, the researchers used it to answer a deeper question: What genetic changes allow cells to survive without frataxin?

This approach ultimately led them to a critical breakthrough.

How Tiny Roundworms Led to a Big Discovery

To dig deeper, the team turned to Caenorhabditis elegans, a microscopic roundworm that is widely used in genetic research. The scientists engineered worms that completely lacked frataxin. Under normal oxygen levels, these worms could not survive. However, when grown in low-oxygen conditions, they lived long enough to be studied.

The researchers then introduced random genetic mutations and searched for rare worms that could survive even when oxygen levels were raised back to normal. This process allowed them to pinpoint genetic changes that could bypass the need for frataxin altogether.

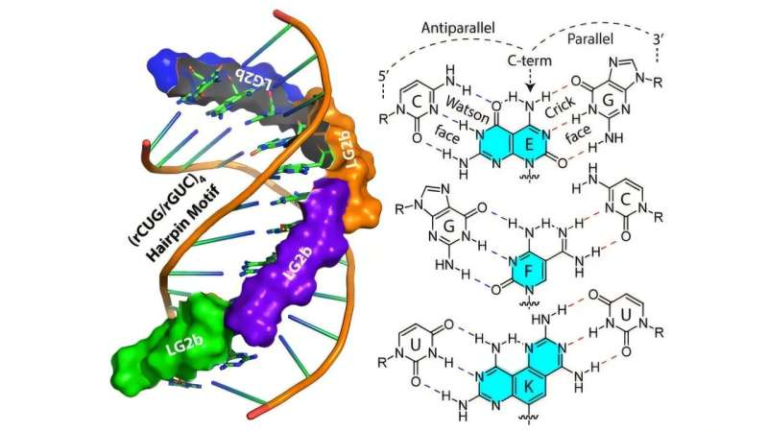

Genome sequencing of these surviving worms revealed mutations in two mitochondrial genes: FDX2 and NFS1.

Why FDX2 Turned Out to Be the Key Player

Further experiments showed that FDX2, a mitochondrial ferredoxin protein, plays a surprisingly important role in frataxin-deficient cells. Under normal conditions, frataxin helps regulate the activity of NFS1, an enzyme required for iron–sulfur cluster formation.

The study found that when frataxin is missing, too much FDX2 actually interferes with iron–sulfur cluster production. Certain mutations in FDX2, or simply reducing its levels, restore balance and allow cells to resume this essential biochemical process.

In simple terms, the problem in FA may not be just “too little frataxin,” but also too much FDX2 relative to frataxin.

This insight is crucial because FDX2 is far more accessible to drug targeting than frataxin itself.

Confirmation in Human Cells and Mouse Models

Importantly, this was not just a worm-specific effect. The researchers confirmed their findings using human cell cultures and mouse models of Friedreich’s ataxia.

In mice, lowering FDX2 levels led to measurable improvements in neurological symptoms, suggesting that this strategy could have real therapeutic value. The results showed improved mitochondrial function and healthier iron–sulfur cluster synthesis, even in the continued absence of normal frataxin levels.

This cross-species consistency strengthens confidence that the mechanism is biologically relevant and potentially translatable to humans.

Why This Matters for Future Treatments

Most previous therapeutic strategies for Friedreich’s ataxia have focused on increasing frataxin levels directly, either through gene therapy or drugs that boost its expression. While promising, these approaches are technically complex and may not work equally well for all patients.

By contrast, modulating FDX2 levels offers a new and potentially simpler path forward. Instead of replacing what is missing, the strategy aims to rebalance the mitochondrial system so it can function despite frataxin deficiency.

Researchers caution, however, that the balance between frataxin and FDX2 is delicate. Reducing FDX2 too much could also be harmful, meaning any future therapy would need to be carefully calibrated.

Extra Context: Why Mitochondria Are Central to Neurodegenerative Diseases

Friedreich’s ataxia is just one of many disorders linked to mitochondrial dysfunction. Because neurons rely heavily on energy production, even small disruptions in mitochondrial pathways can have severe consequences.

Iron–sulfur clusters, in particular, are emerging as a critical vulnerability point in several neurological and metabolic diseases. Research like this not only advances FA treatment prospects but also deepens scientific understanding of mitochondrial biology as a whole.

What Comes Next

While the findings are highly encouraging, researchers emphasize that more pre-clinical work is needed. Future studies will focus on determining how safely FDX2 can be targeted, how much reduction is optimal, and whether this strategy holds up across different tissues and stages of disease.

Human clinical trials are still a step away, but the discovery of FDX2 as a genetic modifier represents a clear and actionable direction for drug development.

Research Paper Reference

Mutations in mitochondrial ferredoxin FDX2 suppress frataxin deficiency

Nature (2025)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09821-2