A New Online Tool Can Reveal Exactly Which Drugs Are Present in Patient Samples

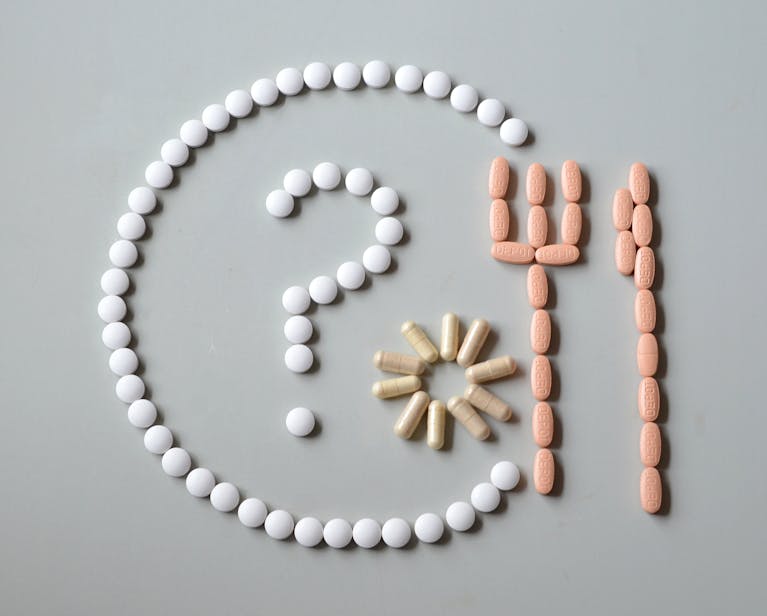

Doctors have long relied on patient memory and medical records to understand which medications someone has taken. But in reality, those sources are often incomplete. People forget drug names, take over-the-counter medicines without mentioning them, use leftover prescriptions, order medications online, or encounter drugs indirectly through food and the environment. All of this makes it surprisingly difficult to know what chemicals are actually circulating in a person’s body.

Now, researchers from the University of California San Diego and their collaborators have introduced a powerful new solution: a publicly available online drug reference library that can directly detect drug exposure from biological samples. The tool, known as the Global Natural Product Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) Drug Library, was described in a study published in Nature Communications and represents a major step forward in how scientists and clinicians can understand real-world drug exposure.

At its core, this new library allows researchers to identify drugs and their breakdown products directly from samples such as blood, urine, breast milk, skin swabs, food, and even environmental water. Instead of guessing what a person might have taken, scientists can now see what is actually there.

Why Tracking Drug Exposure Is So Difficult

Drug exposure is far more complex than a list of prescriptions in a medical chart. Patients may unintentionally omit medications, especially non-prescription drugs. Others may not realize that chemicals from food, pesticides, or environmental sources can show up in their bodies. These hidden exposures matter because drugs can have unexpected effects on biology, interact with one another, and influence disease progression or treatment outcomes.

Missing this information can limit how accurately doctors and researchers interpret health data. That gap is exactly what the GNPS Drug Library aims to close.

How the GNPS Drug Library Works

The foundation of this tool is mass spectrometry, a technique that measures molecules based on their mass and electrical charge. When drugs are analyzed using mass spectrometry, they break apart in predictable ways, creating unique chemical patterns often described as chemical fingerprints.

To build the GNPS Drug Library, researchers collected and cataloged these fingerprints for thousands of drugs, along with their metabolites and related compounds. Each entry in the library includes detailed information about:

- Whether the drug is prescription-based, over-the-counter, or from another source

- The class of medication it belongs to

- Its medical use

- How it works in the body

When an unknown biological sample is analyzed, its chemical signals are compared against this library. Matches reveal which drugs or drug byproducts are present, often uncovering exposures that never appear in medical records.

Testing the Library in Real Patient Samples

To evaluate how well the GNPS Drug Library works in practice, the research team applied it to a wide range of real-world samples using a technique called untargeted metabolomics. Unlike targeted tests that look for specific compounds, untargeted metabolomics scans for thousands of molecules at once, making it ideal for detecting unexpected drug exposures.

The results were striking.

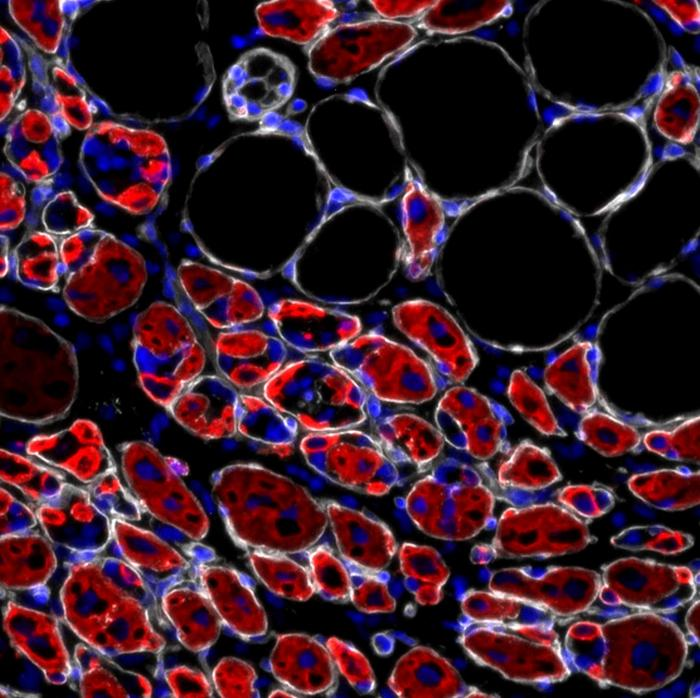

Samples from people with inflammatory bowel disease, Kawasaki disease, and dental cavities frequently showed antibiotics, aligning with standard treatments for those conditions. Similarly, skin swabs from individuals with psoriasis often contained antifungal drugs, reflecting common therapies used to manage skin lesions.

These findings demonstrated that the library could accurately reflect real medication use based purely on chemical evidence.

Insights from the American Gut Project

One of the most extensive tests of the GNPS Drug Library involved samples from nearly 2,000 participants in the American Gut Project, a large international study examining gut microbiome diversity across the United States, Europe, and Australia.

Using the library, researchers detected 75 distinct drugs across these samples. The drugs identified closely matched the most commonly prescribed medication classes in each region, confirming that the system was capturing realistic exposure patterns.

The analysis also revealed notable population-level trends. Participants from the United States carried more detectable drugs per individual than those from Europe or Australia. Differences by sex were also observed: painkillers were more commonly detected in females, while erectile-dysfunction drugs appeared primarily in males.

These findings highlight how drug exposure patterns vary across populations and how chemical analysis can reveal trends that might otherwise remain hidden.

Drug Exposure and Complex Diseases

The GNPS Drug Library also proved valuable for understanding medication use in people with complex, multi-condition health profiles.

In samples from individuals with Alzheimer’s disease, researchers detected cardiovascular and psychiatric medications. This aligns with the reality that Alzheimer’s patients often receive treatment for heart conditions, mood disorders, and other co-existing illnesses.

Similarly, samples from people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) showed not only antiviral medications, but also drugs related to cardiovascular health and mental health. This reflects the higher prevalence of heart disease and depression among HIV patients and demonstrates how the library can capture a fuller picture of medical treatment.

In the HIV study, researchers were even able to link certain antiviral drugs to specific changes in gut-derived molecules, offering direct evidence that medications can reshape the gut microbiome.

Understanding Drugs and the Gut Microbiome

One of the most exciting implications of this work is its relevance to microbiome research. Many drugs interact with gut microbes, altering their composition and metabolic output. These microbial changes can influence immunity, inflammation, and overall health.

By accurately identifying drug exposures, the GNPS Drug Library allows researchers to better understand how medications affect the microbiome and, in turn, how those microbial changes might influence disease outcomes or treatment responses.

Environmental and Food-Related Drug Exposure

The research team also explored non-clinical applications of the library by analyzing more than 3,000 food products. This testing revealed antibiotics in meat products and a pesticide in vegetables that is also used in human medicine.

These findings highlight the potential for hidden environmental drug exposure through food and water. The researchers believe the GNPS Drug Library could be used to monitor reclaimed water, snow, and other environmental samples to better understand how pharmaceutical compounds circulate beyond clinical settings.

Making the Tool Accessible

A key strength of the GNPS Drug Library is its user-friendly online data analysis app. Researchers without specialized pharmacy training can upload their datasets and, with a single click, receive detailed information about which drugs are present, along with visual figures and plots.

This accessibility opens the door for broader use in clinical research, public health, environmental science, and nutrition studies.

Implications for Precision Medicine

By revealing how individuals metabolize medications differently, the GNPS Drug Library could help explain why patients respond unevenly to the same treatment. Understanding real drug exposure may eventually support more personalized and optimized drug therapies, bringing precision medicine closer to everyday clinical practice.

The library is designed to grow over time, and the research team is exploring the use of large language models and generative artificial intelligence to help curate and expand the dataset in the future.

Research Paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65993-5