MIT’s New Aerial Microrobot Can Fly as Fast and Agile as a Bumblebee

Tiny flying robots have long promised big possibilities, from helping locate survivors after earthquakes to exploring places too dangerous or too small for humans and conventional drones. But until recently, one major limitation held them back: they simply couldn’t fly like real insects. They were slow, fragile, and limited to smooth, cautious movements. That gap has now narrowed dramatically.

Researchers at MIT have designed an insect-scale aerial microrobot that can fly with speed, acceleration, and agility comparable to a bumblebee. Thanks to a new AI-driven control system, the robot can perform aggressive aerial maneuvers, including repeated flips, rapid turns, and sharp body tilts, while staying remarkably stable. This work marks a major step forward for bio-inspired robotics and shows that tiny flying machines can finally begin to match the performance of their natural counterparts.

A Tiny Robot with Big Ambitions

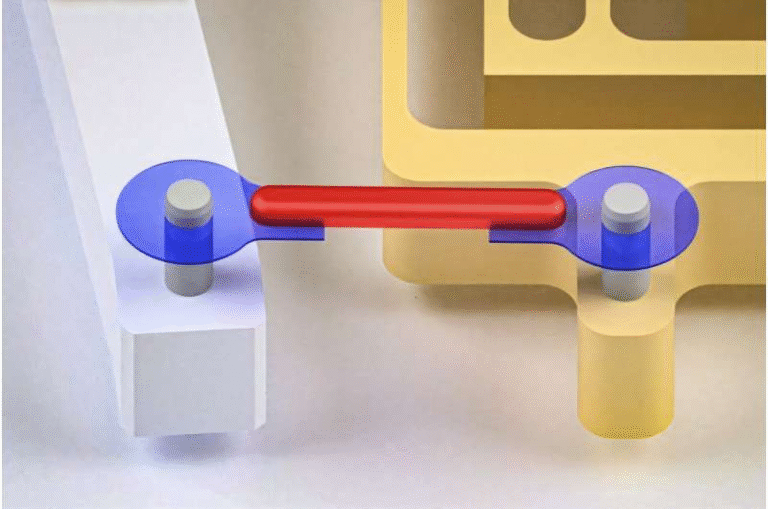

The microrobot developed by MIT’s Soft and Micro Robotics Laboratory is incredibly small. Roughly the size of a microcassette and weighing less than a paperclip, it belongs to a class of machines often referred to as robotic insects. These devices are designed to mimic how real insects fly, using flapping wings rather than spinning rotors like quadcopters.

For more than five years, the research group led by Kevin Chen, associate professor in MIT’s Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, has been refining these robotic insects. The latest version is more durable than earlier designs and uses larger flapping wings, allowing for more powerful and agile motion. The wings are driven by soft, artificial muscles that can flap at extremely high speeds, generating lift and thrust in a way that closely resembles insect flight.

While the hardware had steadily improved, the robot’s controller, essentially its brain, became the main bottleneck. Earlier controllers were hand-tuned by humans, which limited how fast and aggressively the robot could fly. To truly unlock insect-like performance, the team needed a fundamentally new approach to control.

Why Control Is the Hardest Part of Insect-Scale Flight

Flying at such a small scale is incredibly challenging. Insect-scale robots operate in a world dominated by complex aerodynamics, rapid wingbeats, and constant disturbances such as air currents. Even tiny errors in control can cause a crash.

Traditional high-performance controllers can handle complex maneuvers, but they are computationally expensive. Running such controllers in real time on a tiny robot with limited computing power is not practical. This is where the MIT team made a breakthrough by combining advanced control theory with modern AI techniques.

To solve the problem, Chen’s group collaborated with Jonathan P. How, professor in MIT’s Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics and a principal investigator in the Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems. Together, they designed a two-step control framework that balances performance, robustness, and efficiency.

The Two-Step AI Control System

The new control system begins with a model-predictive controller, or MPC. This type of controller uses a detailed mathematical model of the robot’s dynamics to predict future motion and plan an optimal sequence of actions. The MPC can account for physical constraints, such as limits on force and torque, which is essential for avoiding collisions and maintaining stability during aggressive maneuvers.

Using this controller, the robot can plan gymnastic flight paths, including continuous flips, rapid turns, and sharp pitching motions. For example, performing multiple flips in a row requires extremely precise control. If small errors accumulate, the robot would quickly lose stability and crash. The MPC ensures that each maneuver sets up the correct conditions for the next one.

However, while the MPC is powerful, it is also too slow to run directly on the robot in real time. To overcome this, the researchers used the MPC as an expert teacher. They generated carefully selected training data and used a process called imitation learning to train a deep-learning policy.

This AI policy effectively compresses the intelligence of the MPC into a lightweight model that can run extremely fast. During flight, the policy takes in the robot’s position and orientation and outputs real-time control commands, such as thrust and torque. The result is a controller that is both robust and computationally efficient, making real-time aggressive flight possible.

Record-Breaking Performance at Insect Scale

The performance gains achieved with this new control system are striking. Compared to the researchers’ previous best microrobot demonstrations, the new robot achieved a 447 percent increase in speed and a 255 percent increase in acceleration. These numbers bring the robot’s flight capabilities much closer to those of real insects.

In experiments, the robot successfully completed 10 consecutive somersaults in just 11 seconds, a feat that would have been unthinkable for earlier microrobots. Even more impressively, it stayed within 4 to 5 centimeters of its planned trajectory throughout these aggressive maneuvers.

The robot also demonstrated saccade-like movements, a flight behavior commonly observed in insects. During a saccade, an insect pitches aggressively, accelerates rapidly to a new position, and then pitches back to stop. This motion helps insects stabilize their vision and orient themselves in complex environments. Replicating this behavior in a robot opens the door to future onboard vision and sensing systems.

All of this performance was achieved even in the presence of wind disturbances exceeding one meter per second, fabrication imperfections, and even complications such as the robot’s power tether twisting during flight.

Why This Matters Beyond the Lab

This research has important implications far beyond a single robot. In the long term, insect-scale aerial robots could be deployed in scenarios where larger drones struggle. These include search-and-rescue missions, inspection of collapsed buildings, and exploration of confined or cluttered environments.

The ability to fly quickly and aggressively is especially important in real-world settings, where robots must react to unexpected obstacles and disturbances. By showing that soft microrobots can achieve both speed and precision, this work challenges the assumption that tiny robots must be slow and cautious.

While the current system relies on an external computer for control, the researchers believe that simplified versions of the AI policy could eventually run onboard future microrobots. Adding cameras, sensors, and onboard autonomy is a major focus of ongoing research, as is enabling multiple microrobots to coordinate and avoid collisions.

A Step Toward Insect-Level Flight

This work signals a broader shift in how researchers approach microrobotic control. Rather than choosing between high performance and efficiency, the MIT team has shown that it is possible to achieve both at the same time using a smart combination of physics-based modeling and AI.

By bringing robotic flight closer to the natural abilities of insects, this research opens up exciting possibilities for the future of autonomous, insect-scale machines. The gap between biology and robotics is narrowing, and tiny flying robots are starting to prove that they can keep up with nature.

Research paper:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aea8716