Classical Indian Dance Is Teaching Robots How to Use Their Hands Better

Researchers at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) have found an unexpected source of inspiration for improving how robots move their hands: classical Indian dance. By studying the highly precise hand gestures used in Bharatanatyam, one of India’s oldest classical dance forms, scientists have identified new ways to teach robots more flexible, dexterous, and human-like hand movements. The findings also have promising implications for physical therapy, rehabilitation, and prosthetics.

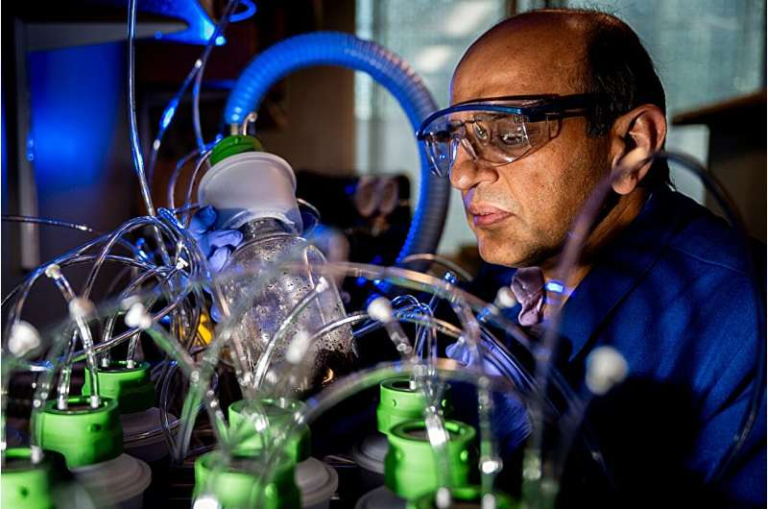

The research was led by Ramana Vinjamuri, a professor at UMBC, and published in the journal Scientific Reports in 2025. At its core, the study explores how structured, artistic hand movements can outperform everyday human grasps when it comes to teaching robots how to move their fingers and joints efficiently.

Understanding the Idea of Hand Movement “Alphabets”

For more than a decade, Vinjamuri’s lab has been studying how the human brain controls complex hand motions. The central concept behind this work is something called kinematic synergies. In simple terms, kinematic synergies describe how the brain groups multiple joint movements together so we can perform complex tasks without consciously controlling every single finger joint.

Instead of thinking of hand movement as hundreds of independent actions, the brain uses a smaller set of building blocks, or synergies, that combine in different ways. Vinjamuri often compares this to language: even though English has hundreds of thousands of words, they are all formed from just 26 letters. Similarly, a wide variety of hand movements can be reconstructed from a limited number of synergies.

Early work in this field focused mostly on natural hand grasps—movements like holding a bottle, picking up a bead, or gripping everyday objects. While effective for basic tasks, these movements may not fully capture the range of flexibility the human hand is capable of.

Why Bharatanatyam Mudras Caught Researchers’ Attention

The turning point came in 2023, when Vinjamuri attended a scientific conference on the brain at the Indian Institute of Technology Mandi, held in the foothills of the Himalayas. During discussions on how ancient Indian traditions could inform modern scientific problems, he began thinking about mudras—the symbolic hand gestures used in Indian classical dance.

In Bharatanatyam, mudras are not casual movements. They are highly precise, deliberate, and expressive, used to tell stories, convey emotions, and represent objects or ideas. Dancers train for years to master these gestures, often maintaining remarkable flexibility and control well into old age.

This sparked an important question for the research team: if these gestures represent a form of “super-healthy” movement, could they provide a richer alphabet of hand motions than the ones derived from everyday human grasps?

Comparing Natural Grasps and Dance Gestures

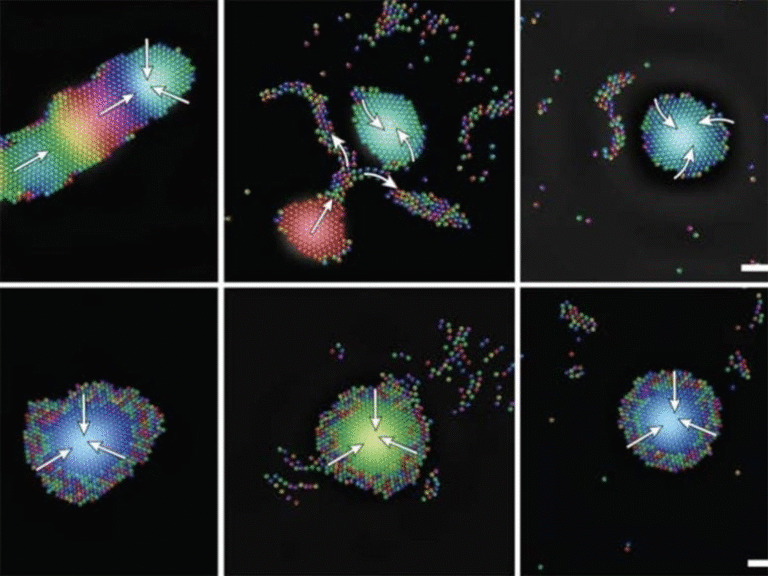

To test this idea, the UMBC team analyzed two distinct datasets. The first consisted of 30 natural hand grasps, covering a range of object sizes from large water bottles to tiny beads. Using mathematical techniques to extract kinematic synergies, the researchers found that six synergies were enough to explain nearly 99% of the variation in these natural movements.

They then applied the same analysis to 30 single-hand mudras from Bharatanatyam. Once again, six synergies emerged, accounting for about 94% of the variation in the dance gestures. While slightly lower than the grasp dataset, this still represented a highly efficient breakdown of complex motion.

The most revealing test came next. The team evaluated how well each set of six synergies could be used to reconstruct 15 letters from the American Sign Language (ASL) alphabet, which were not part of the original datasets. The results were clear: mudra-derived synergies significantly outperformed those derived from natural grasps.

This showed that the movement alphabet extracted from dance gestures was more adaptable and expressive, capable of recreating unfamiliar hand shapes with greater accuracy.

What This Means for Robotics

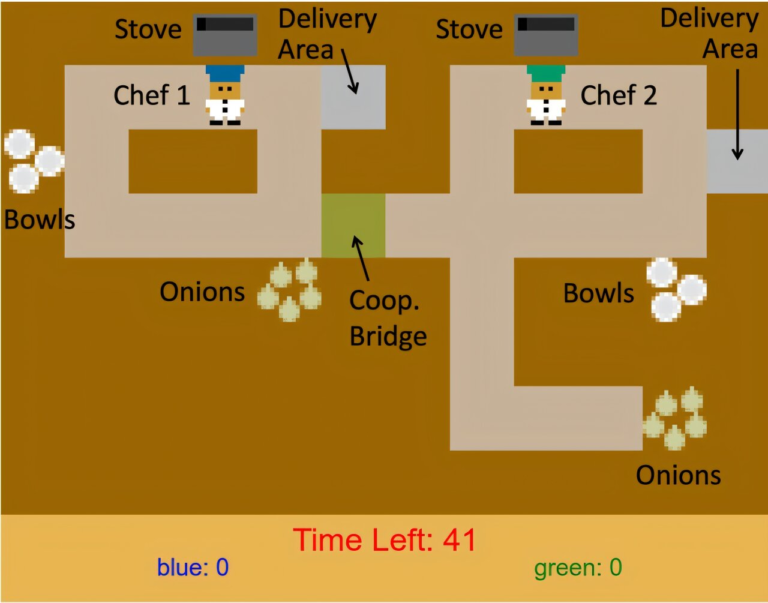

Teaching robots to use their hands has long been a challenge in robotics. Traditional methods often rely on direct imitation or programming each movement individually, which can be inefficient and inflexible. The approach explored in this research shifts the focus toward how humans naturally organize movement in the brain.

The team is now developing ways to teach robots these movement alphabets and how to combine them to form new gestures. They are testing the approach on both a stand-alone robotic hand and a humanoid robot, each with different mechanical constraints. Translating mathematical representations of synergies into physical robotic motion requires careful adaptation, but early results are promising.

One notable aspect of the project is its emphasis on cost-effective implementation. Instead of relying on expensive motion-capture systems, the researchers use a simple camera and software setup to recognize, record, and analyze hand movements. This makes the technology more accessible and scalable.

Potential Applications Beyond Robotics

While robotic hands are an obvious beneficiary, the implications of this research extend further.

In physical therapy and rehabilitation, synergy-based movement models could help design systems that guide patients through exercises more naturally. A virtual coaching platform based on these principles could adapt to individual users and help restore fine motor control after injury or stroke.

The findings also have relevance for prosthetics, where intuitive and flexible control remains a major challenge. By using richer movement alphabets, prosthetic hands could become more responsive and easier for users to control.

There is also potential in human–robot interaction. Robots that can perform expressive hand gestures may communicate more effectively with people, especially in caregiving or educational settings.

Why Dance Offers Unique Insights Into Movement

Dance occupies a unique space between art and biomechanics. Classical forms like Bharatanatyam emphasize precision, repetition, symmetry, and endurance, pushing the human body toward optimized movement patterns. Unlike everyday actions, dance gestures are intentionally structured, making them ideal candidates for studying the upper limits of human dexterity.

From a scientific perspective, these movements provide a valuable dataset of high-quality motor control, offering insights that may not emerge from analyzing routine tasks alone. This study highlights how cultural practices refined over centuries can still contribute meaningfully to modern science and engineering.

A New Way of Thinking About Movement Libraries

Vinjamuri does not believe there is a single, universal “golden alphabet” of hand movements that can do everything. Instead, he envisions building libraries of task-specific movement alphabets. A robot folding laundry might use one set of synergies, while another playing a musical instrument or performing surgery might rely on a different one.

In this framework, dance-derived synergies represent an important addition—especially for tasks requiring high precision and flexibility.

The Bigger Picture

This research sits at the intersection of neuroscience, robotics, cultural tradition, and human health. It demonstrates that innovation does not always come from new technology alone; sometimes, it emerges from looking at ancient practices through a modern scientific lens.

By borrowing from Bharatanatyam, the UMBC team has shown that the future of robotics may be shaped, in part, by the wisdom embedded in human movement traditions.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-25563-7