New Haptic Display Technology Lets You See and Feel 3D Graphics on a Screen

Researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) have developed a new kind of display technology that blurs the line between seeing and touching. This experimental system makes it possible for on-screen graphics to physically rise from a flat surface, allowing users to see and feel dynamic 3D shapes at the same time. Unlike traditional haptic feedback that relies on vibrations or mechanical actuators, this approach directly turns light into touchable motion, opening up new possibilities for interactive screens across many fields.

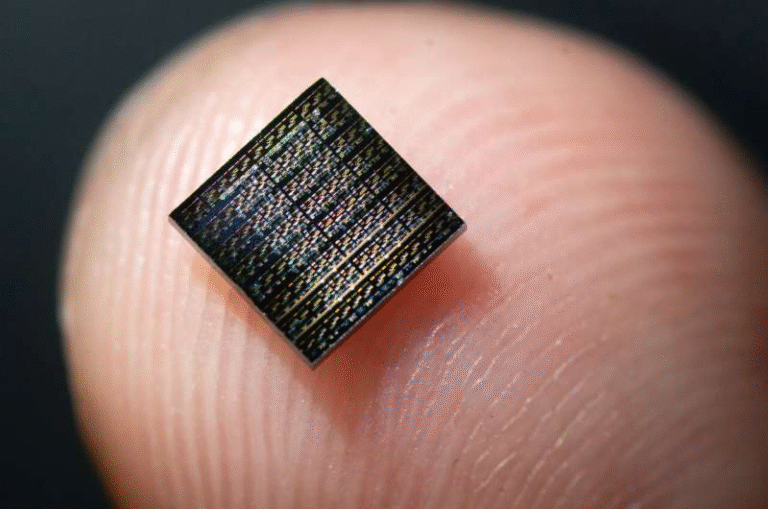

At the center of this breakthrough is a display surface embedded with thousands of tiny, responsive elements known as optotactile pixels. These pixels expand outward when illuminated, forming small bumps that the human finger can clearly detect. When controlled in rapid succession, the pixels create moving shapes, contours, and patterns that behave much like visual animations—except they can also be felt.

How the Technology Works

Each optotactile pixel is about one millimeter in size and contains a carefully engineered internal structure. Inside the pixel is a small, sealed air-filled cavity, topped with a thin suspended graphite film. When a beam of light strikes the pixel, the graphite absorbs the light and heats up very quickly. This heat warms the trapped air beneath it, causing the air to expand.

As the air expands, it pushes the top surface of the pixel outward by as much as one millimeter, creating a noticeable raised bump. When the light turns off, the pixel cools and returns to its flat state. This entire process happens extremely fast, allowing pixels to be activated and deactivated in rapid sequences.

A key feature of the system is that the same light both powers and controls the pixels. Instead of relying on embedded electronics, wires, or mechanical parts inside the display, a low-power scanning laser sweeps across the surface. Each pixel is illuminated for a fraction of a second, enough to trigger the thermal expansion and produce a tactile response.

Because there are no electronics embedded within the display surface itself, the design remains relatively simple, thin, and potentially scalable.

Turning Light Into Touch

The idea behind the technology began in late 2021, when mechanical engineering professor Yon Visell challenged his new PhD student Max Linnander with a deceptively simple question: could light that forms an image also be converted into something people can physically feel?

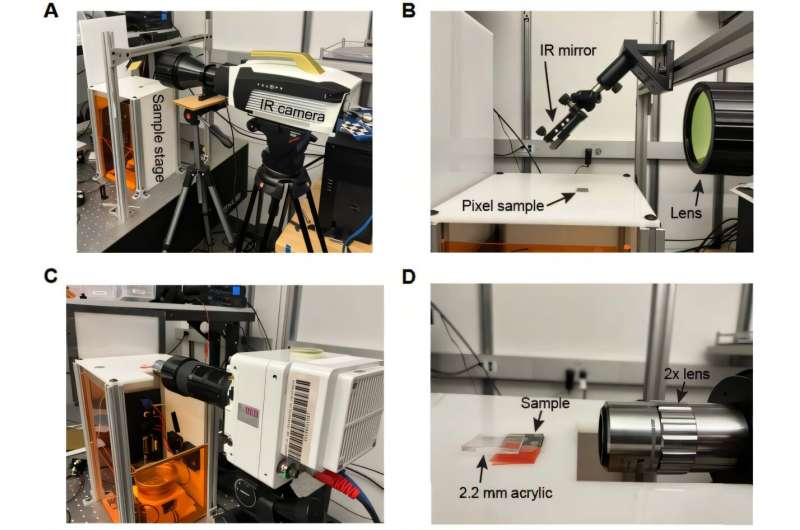

At the time, it was not clear whether the idea was even feasible. The team spent nearly a year developing theoretical models and running computer simulations to understand whether light-driven tactile pixels could work reliably. Once the concept appeared promising, they moved on to building physical prototypes.

Progress was slow. For months, the lab experiments failed to produce meaningful tactile sensations. Then, in December 2022, Linnander demonstrated a breakthrough prototype consisting of a single optotactile pixel activated by brief flashes from a small diode laser. When touched, the pixel produced a clear tactile pulse each time the light flashed. That moment confirmed that the core idea—feeling light—was achievable.

Dynamic Graphics You Can Feel

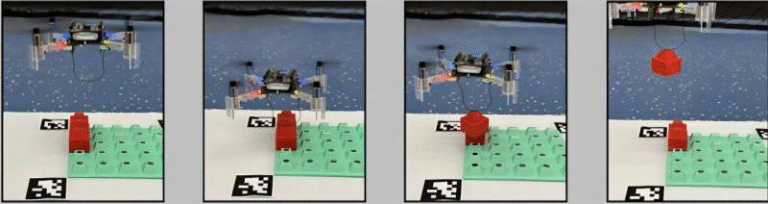

One of the most impressive aspects of the technology is its speed. The pixels respond quickly enough that scanning a laser across the surface creates smooth, continuous tactile animations. Users can feel moving shapes, lines, and characters as the light beam activates pixels in sequence.

The refresh rate is comparable to familiar video displays, meaning the tactile sensations feel continuous rather than choppy or delayed. This makes it possible to render dynamic tactile graphics, not just static bumps.

The UCSB team has already demonstrated display surfaces containing more than 1,500 independently addressable pixels, which is significantly higher than many previously reported tactile displays. According to the researchers, much larger displays are feasible, especially if the system is paired with modern laser video projection technology.

What Users Can Perceive

Beyond engineering the hardware, the researchers also studied how people actually experience these displays. In controlled experiments, participants used their fingertips to explore the surfaces while specific pixels or patterns were activated.

The results showed that users could accurately identify the location of individual pixels with millimeter-level precision. Participants were also able to perceive moving tactile graphics and distinguish different spatial and temporal patterns without difficulty. These findings suggest that the system can deliver a wide range of tactile information, not just simple vibrations or on-off feedback.

The perceptual studies indicate that the display can support complex tactile content, making it suitable for applications that require detailed touch-based interaction.

Why This Is Different From Traditional Haptics

Most existing haptic displays rely on electromechanical actuators, vibration motors, or ultrasonic waves to simulate touch. While effective in some contexts, these approaches often struggle with resolution, scalability, or power efficiency.

The UCSB system stands out because it uses optical addressing, meaning pixels are controlled entirely by light rather than wires or electronic circuits. This reduces mechanical complexity and enables dense arrays of tactile elements without the need for intricate internal hardware.

Interestingly, the concept has historical roots. In the 19th century, inventors including Alexander Graham Bell experimented with focused sunlight to create sound through thermal expansion in air-filled chambers. The UCSB display applies the same physical principle—thermal expansion driven by light—but adapts it to modern digital display technology.

Potential Applications Across Industries

The ability to combine vision and touch on a single surface opens the door to many practical uses.

In automotive interfaces, touchscreens could dynamically form physical buttons or controls when needed, reducing reliance on flat, featureless surfaces. This could improve usability and safety by allowing drivers to feel controls without taking their eyes off the road.

In consumer electronics, phones, tablets, and laptops could offer richer interactions, with tactile feedback that matches on-screen content. Buttons, sliders, or notifications could physically emerge from the display.

In education and accessibility, electronic books could include tangible illustrations, diagrams, or maps that readers can explore by touch. This could be especially valuable for users with visual impairments, providing dynamic tactile content that adapts in real time.

The researchers also envision architectural and mixed-reality applications, such as interactive walls or surfaces that physically respond to digital content, blending the digital and physical worlds in shared spaces.

Challenges and Future Development

Despite its promise, the technology is still at the research and prototype stage. Scaling the displays to very high resolutions, managing heat over long periods of use, and ensuring durability under repeated interaction are all challenges that remain.

Integrating the system into consumer-grade products will require further engineering, particularly to ensure safety, reliability, and cost-effectiveness. However, the underlying concept has now been proven, and the results demonstrate that high-definition visual-haptic displays are technically possible.

A New Way to Interact With Digital Content

At its core, this research introduces a powerful idea: anything you see on a screen could also be something you feel. By transforming projected light into physical motion, the UCSB team has created a new class of displays that challenge long-standing assumptions about how screens work.

As development continues, this optotactile technology could redefine how people interact with digital information, making touch as integral to screens as sight has always been.

Research Paper:

“Tactile Displays Driven by Projected Light” – Science Robotics (2025)

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/scirobotics.adv1383