Researchers Develop an Ultra-Thin Brain-Computer Interface Chip That Could Transform How Humans Connect With Computers

Researchers from Columbia University, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, Stanford University, and the University of Pennsylvania have announced a major leap forward in brain-computer interface (BCI) technology. The new system, called the Biological Interface System to Cortex (BISC), is built around a single, ultra-thin silicon chip that rests directly on the surface of the brain. Designed to be minimally invasive yet extraordinarily powerful, BISC aims to dramatically improve how information flows between the human brain and external computers.

At its core, BISC is about solving a long-standing problem in neurotechnology: how to maximize data transfer to and from the brain while minimizing surgical risk and physical bulk inside the body. Traditional BCIs rely on bulky electronics housed in metal canisters implanted in the skull or chest, connected to the brain through wires. These systems take up significant space, require invasive surgery, and are limited in how much data they can transmit. BISC takes a completely different approach.

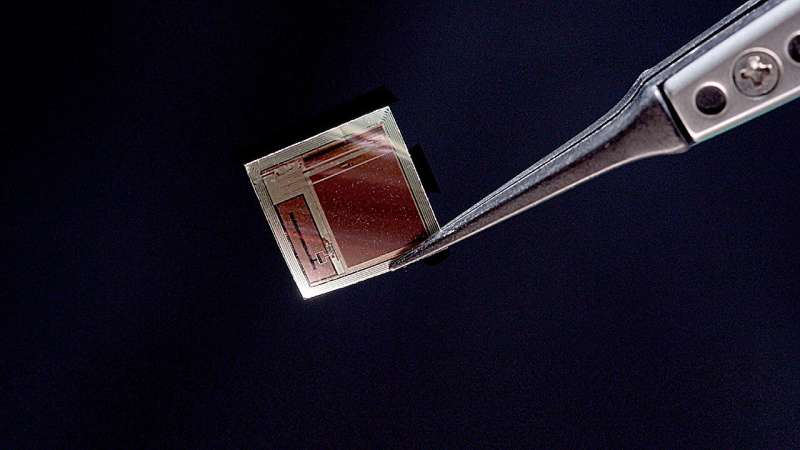

The entire implant is a single complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) integrated circuit, thinned down to just 50 micrometers, roughly the thickness of a human hair. With a total volume of about 3 cubic millimeters, the flexible chip conforms to the brain’s surface and fits neatly into the space between the brain and the skull. Researchers describe it as resting on the brain almost like a piece of wet tissue paper.

A Single Chip That Does Everything

What makes BISC particularly striking is that everything needed for a fully functional brain-computer interface is integrated onto one piece of silicon. The chip includes the circuits required for neural signal recording, electrical stimulation, data conversion, digital control, power management, wireless power delivery, and radio communication. There are no external wires penetrating the brain tissue and no bulky implanted electronics modules elsewhere in the body.

The device functions as a micro-electrocorticography (µECoG) system, meaning it records and stimulates brain activity from the cortical surface rather than penetrating deep into the brain. This approach reduces tissue damage and long-term inflammation while still capturing high-quality neural signals.

In terms of scale, the numbers are impressive. BISC integrates 65,536 electrodes, enabling 1,024 simultaneous recording channels and 16,384 stimulation channels. This density allows researchers to observe and influence neural activity with an unprecedented level of detail across large areas of the brain.

Wireless Power and Data at Unmatched Speeds

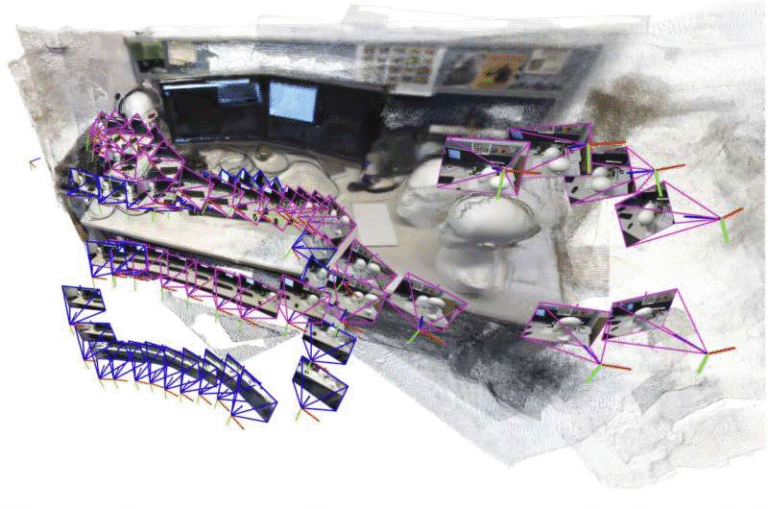

BISC is completely wireless. Power and data are handled through a wearable relay station, which sits outside the body and communicates with the implant using a custom ultrawideband radio link. This link achieves data rates of up to 100 megabits per second, offering at least 100 times higher throughput than existing wireless BCI systems.

The relay station itself behaves like a standard 802.11 WiFi device, effectively creating a wireless network connection between the brain and any external computer. This design allows neural data to be streamed in real time for processing, analysis, and decoding using modern computing systems.

The high bandwidth is not just a technical milestone. It enables neural signals to be fed directly into machine-learning and deep-learning frameworks, allowing advanced AI models to decode complex brain patterns related to movement, vision, speech, perception, or internal brain states.

A New Computing Architecture for Brain Interfaces

BISC is not just a piece of hardware. It represents an entire computing architecture specifically designed for brain-computer interfaces. The system has its own instruction set and is supported by a custom software stack that manages recording, stimulation, data transmission, and integration with external computing platforms.

This tight integration of hardware and software is essential for scaling BCIs beyond experimental setups. By borrowing manufacturing techniques from the semiconductor industry, the researchers emphasize that BISC can be produced at scale, opening the door to wider research use and, eventually, clinical applications.

From the Lab to the Operating Room

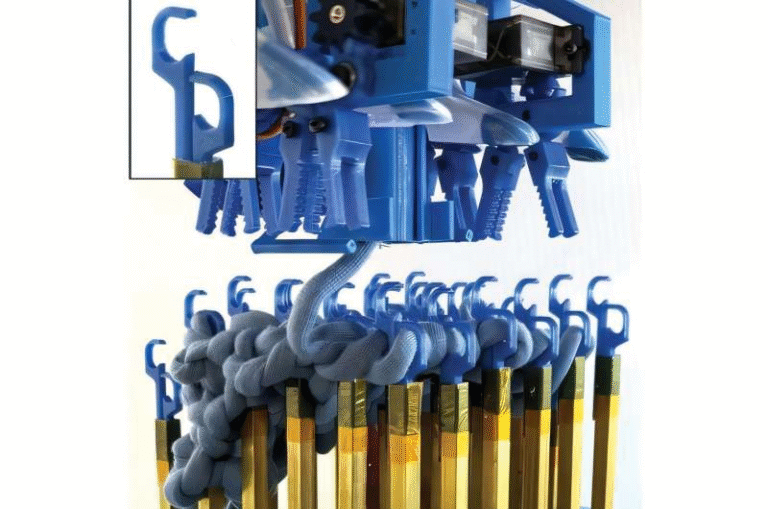

To move the technology toward real-world use, engineers worked closely with neurosurgeons at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Together, they developed surgical methods to implant the paper-thin device safely in preclinical models and tested its signal quality and long-term stability.

The implantation process is designed to be minimally invasive. Surgeons make a small incision in the skull and slide the flexible chip into the subdural space, directly onto the brain’s surface. Because the device does not penetrate brain tissue and does not require wires tethered to the skull, it is expected to reduce tissue reactivity and signal degradation over time.

Short-term intraoperative recordings in human patients are already underway, providing early data on how the device performs in real surgical environments. These studies are an important step toward future long-term implants.

Potential Medical Impact

The researchers see broad potential for BISC in treating and managing neurological conditions. The system could play a role in addressing epilepsy, spinal cord injury, ALS, stroke, paralysis, and blindness. By enabling high-resolution recording and precise stimulation, the technology could help restore motor function, speech, or vision, or assist in managing seizures and other neurological symptoms.

Because BISC allows both reading from and writing to the brain, it supports closed-loop systems where neural activity is continuously monitored and adjusted in real time. This capability is especially important for adaptive neuroprosthetics and responsive therapies.

Collaboration Across Disciplines

The development of BISC reflects a deep collaboration between engineers, neuroscientists, and clinicians. The project brought together Columbia’s expertise in microelectronics, Stanford’s and Penn’s leadership in computational and systems neuroscience, and NewYork-Presbyterian’s surgical innovation. The work was supported by the Neural Engineering Systems Design program of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

Extensive preclinical testing was carried out in both the motor and visual cortices, demonstrating the system’s versatility across different brain regions. Researchers also highlighted the potential for future versions of the platform to interface with other modalities, such as light and sound, further expanding its capabilities.

Commercialization and the Road Ahead

To accelerate translation beyond the lab, members of the research team launched Kampto Neurotech, a spin-off company developing commercial versions of the BISC chip for preclinical research. The company is also raising funds to advance the system toward long-term human use.

In a broader context, BISC arrives at a time of growing interest in brain-computer interfaces, driven by rapid advances in artificial intelligence. High-resolution neural data combined with powerful AI models could lead to more natural and seamless interaction between humans and machines. While clinical applications remain the primary focus, the technology also hints at future possibilities for cognitive augmentation and deeper brain–AI integration.

By shrinking complex electronics into a nearly invisible form factor and dramatically increasing data bandwidth, BISC represents a fundamentally different way of building brain-computer interfaces. It is smaller, safer, faster, and more scalable than previous systems, and it sets a new benchmark for what implantable neurotechnology can achieve.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-025-01509-9