Scientists Discover a New Nuclear Island Where Long-Trusted Magic Numbers Stop Working

For decades, nuclear physicists have relied on a surprisingly tidy idea: atomic nuclei follow a shell structure, much like electrons in atoms, and certain numbers of protons or neutrons — known as magic numbers — create especially stable, spherical nuclei. But every so often, nature refuses to follow the rules. In a recent breakthrough, scientists have uncovered a completely new region of nuclear behavior where these magic numbers collapse in an unexpected place: a nucleus with equal numbers of protons and neutrons.

This discovery introduces what researchers now call an isospin-symmetric Island of Inversion, a finding that reshapes how scientists think about nuclear structure and the forces that hold matter together.

What Are Islands of Inversion?

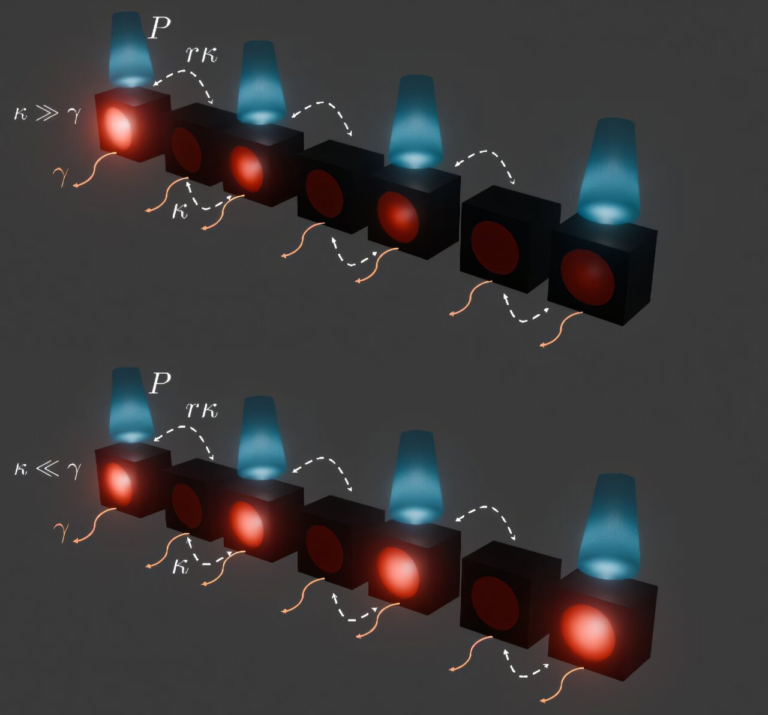

In nuclear physics, an Island of Inversion refers to a region on the nuclear chart where the normal shell structure breaks down. Instead of neatly filling energy levels, protons and neutrons jump across large energy gaps, producing nuclei that are highly deformed rather than spherical.

Until now, every known Island of Inversion shared one thing in common: they occurred in neutron-rich, highly unstable nuclei that are far from the nuclei found naturally on Earth. Famous examples include:

- Beryllium-12 at neutron number N = 8

- Magnesium-32 at N = 20

- Chromium-64 at N = 40

These nuclei defied expectations by showing strong collective motion and deformation where none was predicted. What scientists did not expect was to find similar behavior in a nucleus sitting right on the N = Z line, where the number of protons equals the number of neutrons.

Why Proton–Neutron Symmetry Matters

Nuclei with equal numbers of protons and neutrons occupy a special place in nuclear physics. This symmetry enhances proton–neutron interactions and plays a key role in understanding the strong nuclear force. However, such nuclei are extremely difficult to produce in laboratories, especially when they are heavy and short-lived.

Because of these experimental challenges, the N = Z region has remained less explored compared to neutron-rich territories. The new discovery shows that this region still holds major surprises.

The Focus on Molybdenum Isotopes

The international research team focused on two specific isotopes:

- Molybdenum-84 (Mo-84) with Z = 42 and N = 42

- Molybdenum-86 (Mo-86) with Z = 42 and N = 44

At first glance, these nuclei are nearly identical, differing by just two neutrons. Yet the experiments revealed that their internal structures are dramatically different.

How the Experiments Were Done

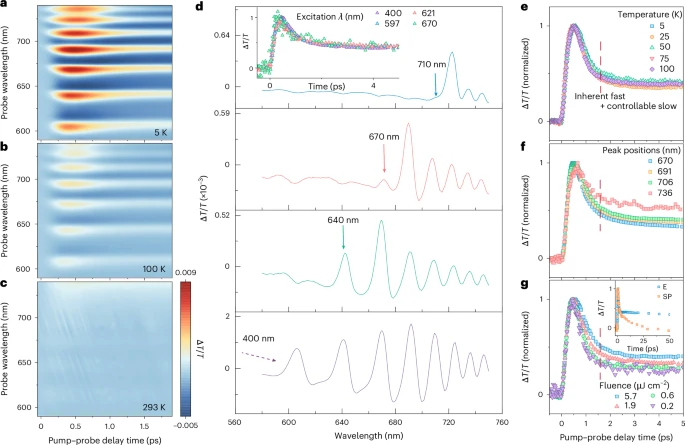

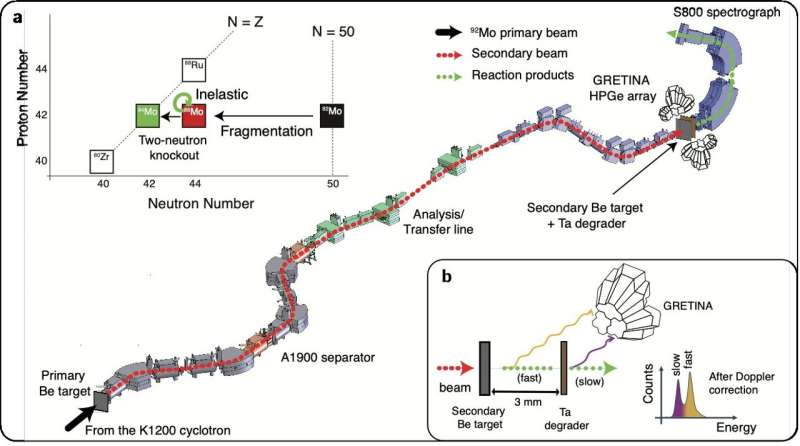

The experiments were carried out using rare-isotope beams at Michigan State University. Researchers began by accelerating Mo-92 ions and smashing them into a beryllium target. This violent collision produced a wide variety of nuclear fragments.

An A1900 fragment separator was used to isolate fast-moving Mo-86 nuclei. These nuclei then struck a second target, where some were excited and others were transformed into Mo-84 by removing two neutrons.

As the excited nuclei relaxed back to their ground states, they emitted gamma rays. These gamma rays carry precise information about the internal motion and shape of the nucleus.

To capture this information, the team used:

- GRETINA, a high-resolution gamma-ray tracking detector

- TRIPLEX, an advanced device capable of measuring nuclear lifetimes lasting only trillionths of a second

The experimental data were then compared with GEANT4 Monte Carlo simulations, allowing the scientists to extract extremely precise lifetimes of excited states and deduce the degree of nuclear deformation.

A Stark Contrast Between Mo-84 and Mo-86

The results were striking. Mo-84 displayed an exceptionally large degree of collective motion, meaning many protons and neutrons were acting together rather than independently. This behavior is a hallmark of strong nuclear deformation.

In nuclear physics terms, Mo-84 undergoes a massive 8-particle–8-hole excitation. In this process, eight nucleons jump across a major shell gap into higher-energy orbitals, leaving behind eight vacancies. The more nucleons involved in such coordinated motion, the more distorted the nuclear shape becomes.

In contrast, Mo-86 showed only modest 4-particle–4-hole excitations. As a result, it remained much closer to a normal, less deformed structure.

This sharp difference confirms that Mo-84 sits inside a newly discovered Island of Inversion, while Mo-86 lies just outside it — despite the two isotopes being separated by only two neutrons.

The Role of Three-Nucleon Forces

One of the most important theoretical outcomes of this study is the role of three-nucleon forces. Traditional nuclear models often focus on interactions between pairs of nucleons. However, the calculations showed that two-nucleon forces alone cannot reproduce the observed structure of Mo-84.

Only when three nucleons interacting simultaneously are included in the models does the strong deformation of Mo-84 emerge. This provides powerful new evidence that three-body forces are essential for accurately describing certain regions of the nuclear chart.

Why This Discovery Is a Big Deal

This is the first known Island of Inversion discovered in a proton–neutron symmetric nucleus. That alone makes it a landmark result. But the implications go further:

- It challenges long-standing assumptions about where structural inversions can occur

- It expands the known nuclear landscape into regions once thought to be well understood

- It provides a new testing ground for advanced nuclear theories and force models

In short, even in parts of the nuclear chart that look familiar and symmetric, nature still finds ways to surprise us.

A Broader Look at Nuclear Shell Structure

The nuclear shell model has been one of the most successful frameworks in physics, explaining why certain nuclei are especially stable and why others decay quickly. Discoveries like this remind scientists that the model is not universal and that shell structures can evolve depending on proton–neutron balance, shell gaps, and many-body interactions.

Islands of Inversion serve as natural laboratories for studying how collective motion, deformation, and nuclear forces emerge from the complex behavior of many interacting particles.

What Comes Next?

This discovery opens the door to exploring whether other isospin-symmetric nuclei may also host unexpected structural inversions. As rare-isotope facilities become more powerful and detectors more precise, researchers expect to uncover additional surprises along the N = Z line.

Each new finding helps refine nuclear models that are essential not only for basic science, but also for understanding astrophysical processes, such as how heavy elements form in stars and stellar explosions.

Research Paper:

Abrupt structural transition in exotic molybdenum isotopes unveils an isospin-symmetric island of inversion

Nature Communications (2025)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65621-2