The First Direct Observation of the Hexatic Phase in Ultra-Thin Two-Dimensional Materials

Scientists have long understood how everyday materials melt. Ice turns into water, metals soften into liquids, and the transition usually happens abruptly. But when materials become extremely thin—so thin they are essentially two-dimensional—the familiar rules of melting no longer apply. A new study from researchers at the University of Vienna has now confirmed this in a striking way, with the first direct observation of the hexatic phase in an atomically thin crystal. This exotic state of matter sits between solid and liquid and has been theorized for decades but never before seen in a real, strongly bonded 2D material.

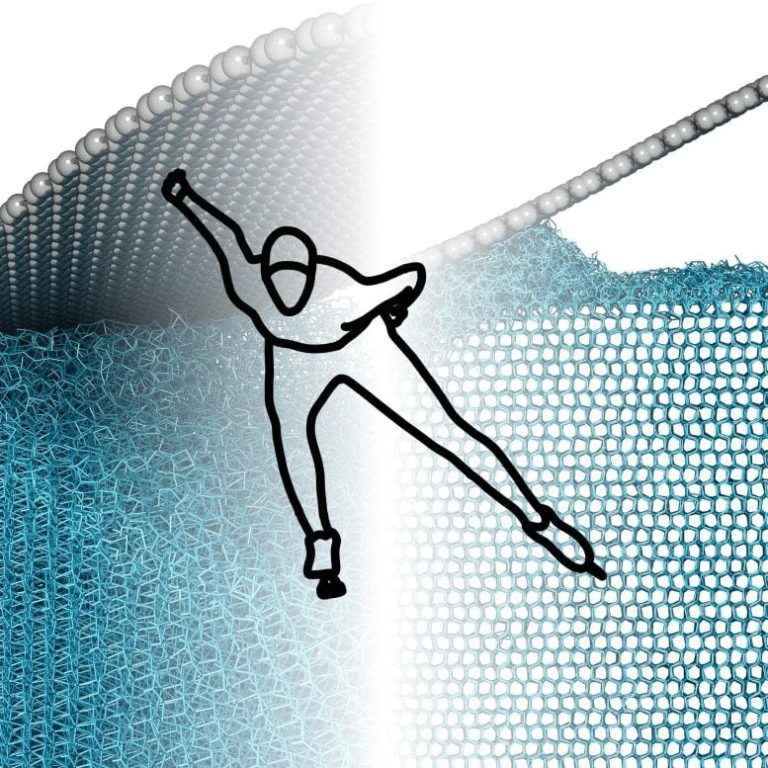

This breakthrough was achieved by directly filming the melting of a single-layer crystal of silver iodide (AgI) at the atomic scale. The findings not only confirm a long-standing prediction in physics but also challenge parts of existing theory, opening a new chapter in the study of how matter behaves in two dimensions.

Why Melting Changes in Two Dimensions

In three-dimensional materials, melting is straightforward. A solid maintains both positional and angular order—atoms are arranged in a regular pattern, and the angles between them are fixed. When melting occurs, both types of order disappear almost simultaneously, resulting in a liquid.

However, theoretical work from the 1970s predicted that in two-dimensional systems, melting could follow a very different path. Instead of a single step, the process could involve an intermediate phase called the hexatic phase. In this state, atoms lose their strict positional order, meaning distances between them become irregular like in a liquid. At the same time, they retain a degree of angular order, especially a six-fold (hexagonal) symmetry, which is characteristic of many crystalline solids.

This hybrid behavior makes the hexatic phase neither fully solid nor fully liquid. While it has been observed in simplified model systems—such as layers of colloidal particles or densely packed plastic spheres—it remained unclear whether it could exist in real, covalently bonded materials. That uncertainty has now been resolved.

Capturing an Elusive State of Matter

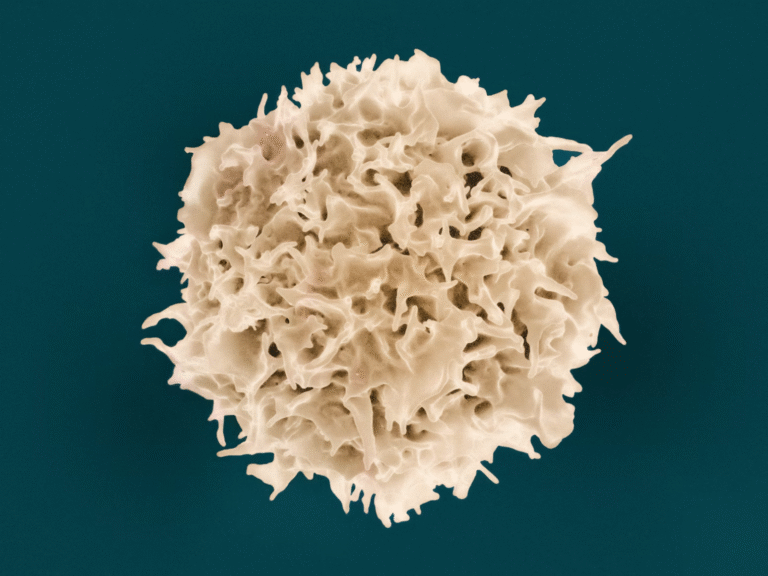

The research team used an innovative experimental setup to observe this fragile process. Atomically thin crystals are notoriously difficult to study because they tend to curl, tear, or degrade under heat. To overcome this, the scientists encapsulated a single layer of silver iodide between two sheets of graphene, creating what they described as a protective “graphene sandwich.” This structure stabilized the crystal while still allowing it to melt freely.

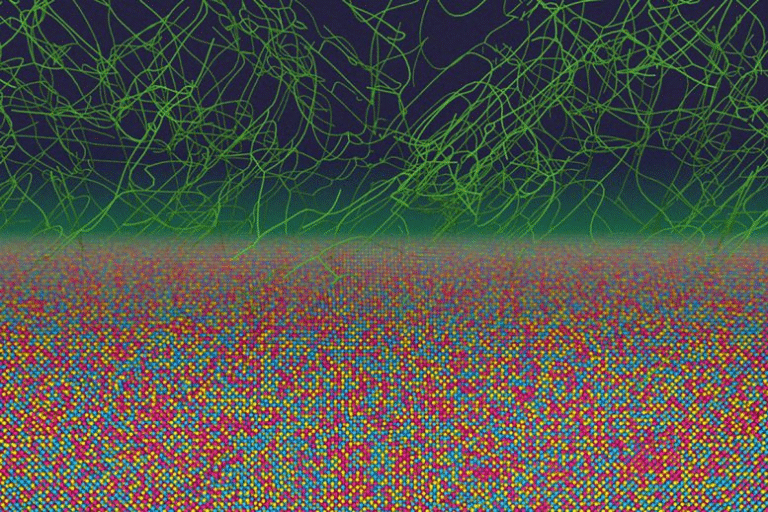

The experiment was conducted inside a state-of-the-art scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) equipped with a high-precision heating stage. Using this setup, the team gradually heated the sample to temperatures exceeding 1,100°C, approaching the melting point of silver iodide. This allowed them to record thousands of high-resolution images showing how individual atoms moved as the crystal transitioned through different phases.

Tracking the motion of so many atoms would have been impossible with traditional analysis methods. To solve this, the researchers turned to neural networks trained on large simulated datasets. These AI tools enabled them to reliably identify atomic positions and follow changes in structure frame by frame, producing a detailed real-time view of melting at the atomic scale.

The Clear Signature of the Hexatic Phase

The analysis revealed something remarkable. Within a narrow temperature window—approximately 25°C below the melting point of silver iodide—the crystal entered a distinct hexatic phase. In this regime, the atomic arrangement lost long-range positional order, but the angular relationships between neighboring atoms remained largely intact.

To confirm that this was truly a hexatic phase and not an experimental artifact, the team also performed electron diffraction measurements. These measurements showed patterns consistent with orientational order but lacking the sharp features associated with a fully crystalline solid. Together with the real-space imaging, this provided strong, independent evidence that the hexatic phase was genuinely present.

This marks the first direct observation of the hexatic phase in an atomically thin, strongly bonded material, resolving a question that has remained open for decades.

A Surprise That Challenges Theory

One of the most intriguing aspects of the study is how the transitions between phases occurred. According to classical theories of two-dimensional melting, both transitions—solid to hexatic and hexatic to liquid—should be continuous, meaning they happen gradually.

What the researchers observed was more complex. The transition from the solid phase to the hexatic phase was indeed continuous, aligning with theoretical expectations. However, the transition from the hexatic phase to the liquid phase was abrupt, resembling the sudden melting seen in three-dimensional materials like ice turning into water.

This unexpected behavior suggests that melting in real two-dimensional crystals is more nuanced than previously thought. It indicates that existing theories may need to be refined to fully account for the role of strong chemical bonding and atomic-scale interactions in 2D systems.

Why Silver Iodide Matters

Silver iodide is not just a convenient test material. It has long been studied for its unusual properties, including its role in cloud seeding and its ionic conductivity at high temperatures. In its bulk form, silver iodide already displays interesting phase behavior, making it an ideal candidate for exploring how melting changes when the material is reduced to a single atomic layer.

By showing that a covalently bonded material like silver iodide can host a hexatic phase, the study demonstrates that this exotic state of matter is not limited to soft or artificial systems. It is a genuine feature of real materials under the right conditions.

The Broader Significance for Materials Science

This discovery has implications that extend well beyond silver iodide. Many emerging technologies rely on two-dimensional materials, from graphene-based electronics to ultra-thin sensors and membranes. Understanding how these materials behave near their melting points is essential for designing devices that can withstand extreme conditions.

The work also highlights the growing importance of advanced microscopy combined with artificial intelligence. Being able to directly observe atomic motion in real time provides insights that are simply inaccessible through indirect measurements alone. As these techniques continue to improve, they are likely to reveal even more unexpected states of matter and transitions at the smallest scales.

What the Hexatic Phase Teaches Us About Matter

At a deeper level, the observation of the hexatic phase reinforces an important idea in physics: dimensionality matters. When materials are confined to two dimensions, they can behave in ways that are fundamentally different from their three-dimensional counterparts. This study provides a vivid, atomic-scale demonstration of that principle.

By confirming the existence of the hexatic phase in a real, strongly bonded 2D crystal—and by revealing surprising features in how it forms and disappears—the researchers have given scientists a new framework for thinking about phase transitions in reduced dimensions.

Research Reference

Hexatic phase in covalent two-dimensional silver iodide, Science (2025)

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adv7915