Scientists Have Mapped Mars’ Ancient River Drainage Systems for the First Time

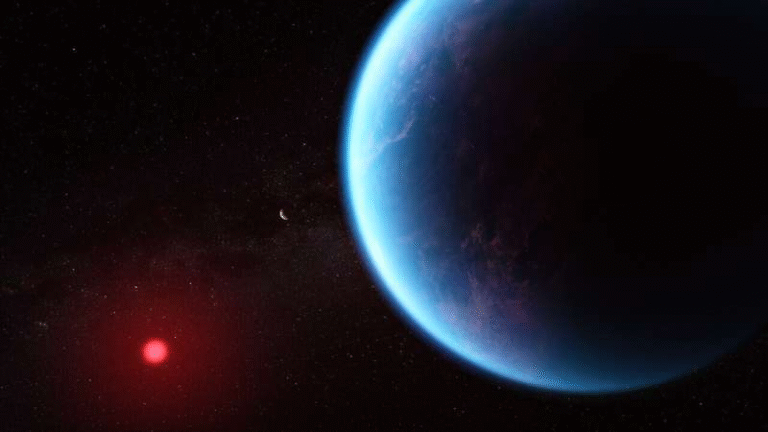

Scientists have long known that water once flowed across Mars, carving valleys, filling craters, and shaping the planet’s surface billions of years ago. What they did not fully understand—until now—was how organized those rivers really were. A new study from researchers at The University of Texas at Austin has finally provided the first planet-wide map of large river drainage systems on Mars, revealing a surprisingly structured and interconnected ancient landscape that could have been one of the most promising environments for life on the Red Planet.

A wetter Mars shaped by rain and flowing rivers

Billions of years ago, Mars looked very different from the cold, dry world we see today. Scientists believe that rainfall once occurred across the planet, allowing water to collect in valleys and rivers. These rivers flowed downhill, sometimes filling entire craters before spilling over their rims, and were eventually funneled into larger canyons. Some of that water may have traveled long distances, possibly even reaching a large ancient ocean thought to have existed in Mars’ northern lowlands.

On Earth, regions shaped by major river systems—such as the Amazon River basin—are among the most biologically rich places on the planet. They concentrate water, nutrients, and sediment, creating ideal conditions for life. Researchers believe that similar river systems on ancient Mars could have served as potential cradles for life when liquid water was stable on the surface.

Identifying Mars’ large river basins

The new study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, represents the first systematic, global identification of large river drainage systems on Mars. The research was led by Abdallah S. Zaki, a postdoctoral fellow at UT Austin, along with Timothy A. Goudge, an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences.

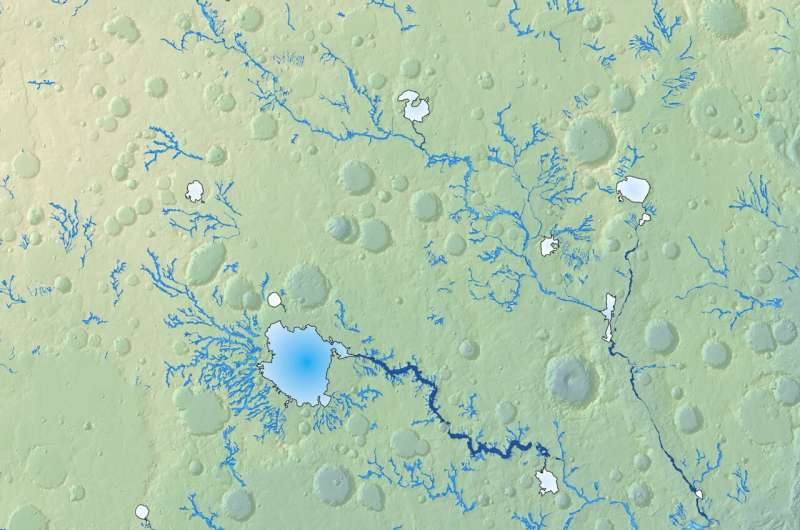

Instead of focusing on individual valleys or channels, the researchers took a broader approach. They combined previously published datasets that mapped Martian valley networks, ancient lakes, rivers, canyons, and sediment deposits. By piecing these features together, they were able to outline complete drainage systems and measure their total areas.

Their analysis revealed 19 large clusters of connected valleys, streams, lakes, and sediment pathways. Out of these, 16 clusters formed continuous drainage basins covering 100,000 square kilometers or more. On Earth, this size threshold is what scientists use to define a large drainage basin.

This marks the first time scientists have been able to clearly see how Mars’ rivers were organized at a planetary scale, rather than as scattered, isolated features.

How Mars compares to Earth

Large river basins are far more common on Earth than on Mars. Our planet has 91 drainage basins that exceed 100,000 square kilometers. The largest, the Amazon River basin, spans about 6.2 million square kilometers. Even relatively modest systems, such as Texas’ Colorado River basin, just qualify as large at roughly 103,300 square kilometers.

Mars, by contrast, has far fewer large basins. One major reason is geology. Earth’s surface is constantly reshaped by tectonic activity, which builds mountains, creates valleys, and redirects water flow over time. This complex topography helps rivers merge into massive, interconnected systems.

Mars lacks active plate tectonics. Without mountain-building and crustal recycling, the planet developed fewer opportunities for rivers to link up into vast drainage networks. As a result, most of Mars is covered by a mosaic of smaller drainage systems, rather than continent-spanning river basins.

Why these basins matter for life

Although the large drainage systems identified in the study cover only about 5% of Mars’ ancient terrain, their importance is outsized. The researchers found that these basins account for roughly 42% of all the sediment eroded by rivers on Mars.

That matters because sediment transports nutrients. The longer water flows across rock surfaces, the more chemical interactions take place between water and minerals. These reactions can produce energy sources and chemical gradients—key ingredients for life.

In simple terms, the larger and longer-lasting the river system, the better the chances that habitable conditions could have existed. Even if life never arose on Mars, these environments would have been among the most favorable places for it to try.

While smaller drainage systems may also have been habitable, the researchers argue that the 16 large drainage basins are the most promising targets for future studies of Mars’ ancient habitability.

Implications for future Mars missions

This research has practical implications for the future of Mars exploration. Landing sites for rovers and sample-return missions are chosen carefully, and understanding where sediment accumulated over long distances can help scientists prioritize locations most likely to preserve biosignatures, or signs of past life.

Because sediment can bury and protect chemical and geological evidence for billions of years, these large drainage systems may hold some of the best-preserved records of Mars’ watery past. Identifying where that sediment ultimately ended up will be a key next step.

Researchers emphasize that this work provides a new framework for thinking about Mars—not just as a planet with ancient rivers, but as one that once had organized hydrologic systems similar, in some ways, to those on Earth.

Extra context: how scientists study ancient rivers on Mars

Scientists study Mars’ ancient rivers using data from orbiters such as the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter. High-resolution images reveal valley shapes, channel patterns, and sediment deposits, while elevation data helps determine how water once flowed across the surface.

By analyzing these features, researchers can distinguish between valleys carved by water and those formed by other processes, such as lava flows. Over time, assembling these datasets allows scientists to reconstruct entire river networks, even though the water itself vanished billions of years ago.

Mars’ river valleys are especially valuable because the planet lacks active erosion from vegetation, oceans, and plate tectonics. In many places, ancient features are remarkably well preserved, offering a window into conditions from the planet’s earliest history.

A major step in understanding Mars’ past

This new mapping effort represents a significant leap forward in understanding how Mars once worked as a planet. It shifts the focus from isolated channels to planet-scale drainage systems, helping scientists better understand Mars’ climate, surface evolution, and potential for life.

As future missions continue to explore Mars, these newly identified river basins will likely play a central role in deciding where to look next for answers about the planet’s ancient habitability.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2514527122