Solar Wind Storms May Explain the Long-Standing Mystery of Uranus’s Extreme Radiation Belts

For nearly four decades, scientists have puzzled over a strange and unexpected discovery made during NASA’s Voyager 2 flyby of Uranus in 1986. The spacecraft detected exceptionally intense electron radiation belts around the ice giant—far stronger than scientists had predicted based on what was known about planetary magnetospheres elsewhere in the solar system. Now, new research suggests that this mystery may finally have a convincing explanation, and it points directly to the powerful influence of solar wind storms.

Researchers from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) believe that Uranus was experiencing an unusual and intense space weather event at the exact time Voyager 2 passed by. According to their analysis, this event could have temporarily supercharged Uranus’s radiation belts, creating conditions that made the planet appear far more extreme than it normally is.

What Voyager 2 Found at Uranus

When Voyager 2 reached Uranus in January 1986, it delivered humanity’s first and so far only close-up look at the planet’s magnetic environment. One of the most surprising findings was the presence of a powerful electron radiation belt that exceeded expectations by a wide margin. Based on comparisons with Earth, Jupiter, and Saturn, scientists expected Uranus’s radiation belts to be relatively modest. Instead, Voyager 2 measured electron energy levels that were essentially off the charts.

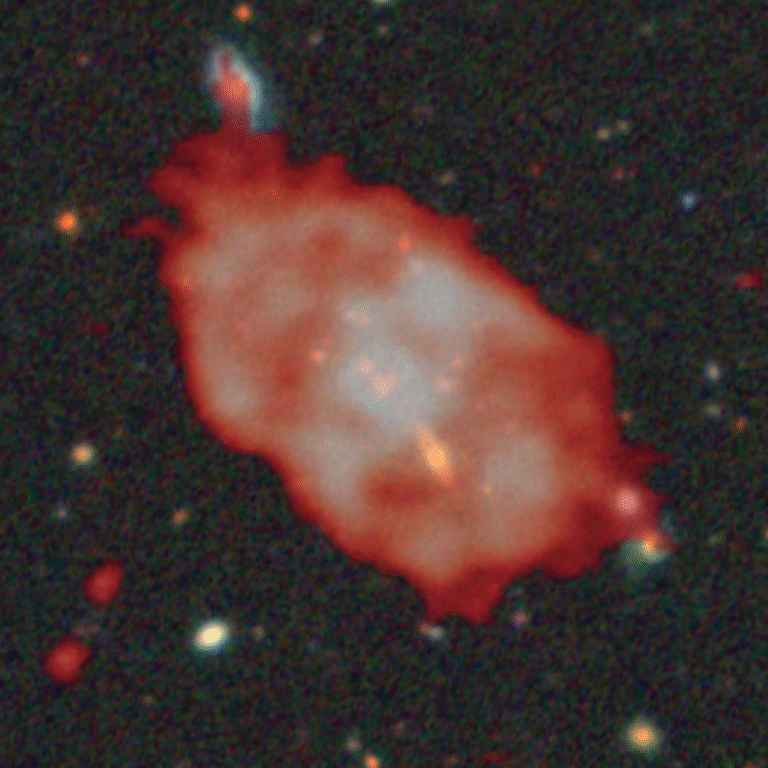

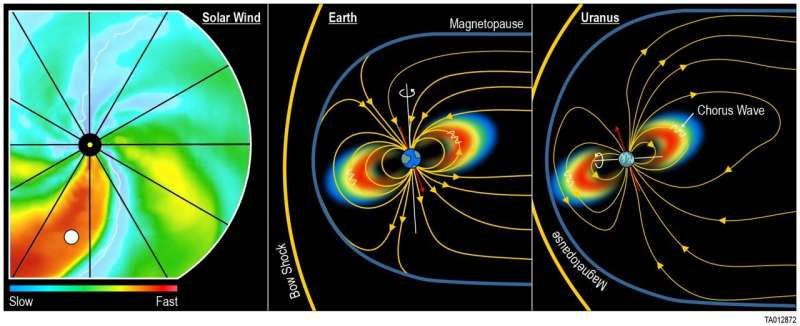

This posed a serious problem for planetary scientists. Uranus is unlike any other planet in the solar system. Its magnetic field is highly tilted relative to its rotation axis and offset from the planet’s center. It also rotates on its side, creating an unusually complex magnetosphere. While these odd characteristics explained some unusual behavior, they did not fully account for the extreme radiation environment detected by Voyager 2.

For years, researchers debated whether Uranus naturally maintains such intense radiation belts or whether Voyager 2 had encountered something unusual.

A Fresh Look Using Modern Space Weather Science

The new SwRI study takes advantage of decades of progress in understanding Earth’s radiation belts. Since the 1980s, scientists have gathered extensive data on how solar wind disturbances interact with Earth’s magnetosphere, especially during major solar storms.

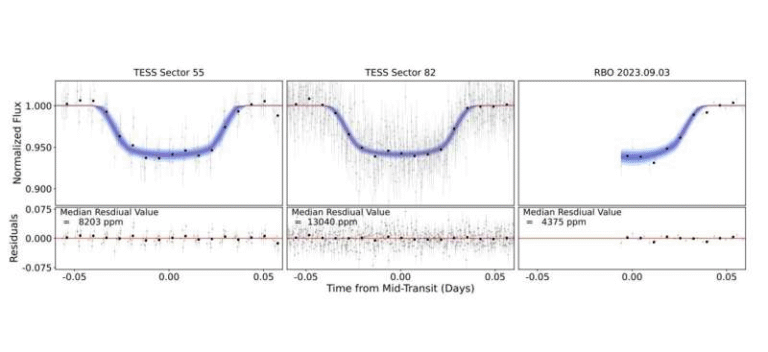

The researchers reexamined Voyager 2’s Uranus data and compared it to modern observations of Earth during strong solar wind events, including a well-documented event that occurred in 2019. That Earth-based event involved a powerful solar wind structure that caused dramatic acceleration of radiation belt electrons.

This comparative approach led the researchers to a compelling conclusion: Voyager 2 likely arrived at Uranus during a major solar wind disturbance.

The Role of Co-Rotating Interaction Regions

At the center of this new explanation is a phenomenon known as a co-rotating interaction region, or CIR. CIRs form when fast-moving streams of solar wind overtake slower-moving streams, creating regions of compressed plasma and enhanced magnetic activity. These structures can persist for long periods and are known to drive intense geomagnetic storms at Earth.

According to the study, a CIR was probably passing through the Uranian system when Voyager 2 made its flyby. This would have dramatically altered Uranus’s magnetosphere, injecting energy and triggering powerful electromagnetic activity.

One particularly important effect of such disturbances is the generation of high-frequency electromagnetic waves, often referred to as chorus waves. These waves are now known to play a crucial role in accelerating electrons within radiation belts.

Rethinking the Behavior of Electromagnetic Waves

Back in 1986, scientists believed that the intense waves observed by Voyager 2 would mainly act to scatter energetic electrons, causing them to collide with Uranus’s atmosphere and be lost from the system. This interpretation made the strong radiation belts even harder to explain.

However, modern research has revealed that under certain conditions, these same waves can do the opposite. Instead of draining energy, they can rapidly accelerate electrons, pushing them to much higher energies and effectively strengthening radiation belts.

The SwRI team argues that this is exactly what happened at Uranus. The solar wind disturbance likely triggered exceptionally strong wave activity, which then pumped energy into the planet’s radiation belts, producing the extreme electron levels Voyager 2 observed.

Evidence from Earth’s Radiation Belts

The researchers point to Earth’s experience in 2019 as a useful comparison. During that event, a solar wind structure similar to a CIR caused one of the most dramatic radiation belt electron acceleration episodes ever recorded. Satellites observed electrons reaching unusually high energies in a very short time.

If Earth’s magnetosphere can respond this dramatically to solar wind disturbances, it is reasonable to think that Uranus—already possessing a uniquely structured magnetic field—could experience even more extreme effects under similar conditions.

This insight suggests that the radiation environment Voyager 2 encountered may not represent Uranus’s typical state, but rather a temporary and highly energized snapshot.

What This Means for Uranus and Beyond

If the new interpretation is correct, it reshapes how scientists think about Uranus’s magnetosphere. Instead of being permanently extreme, the planet’s radiation belts may be highly variable, responding strongly to changes in solar wind conditions.

This also has implications for Neptune, another ice giant with a complex magnetic field that has only been visited once by Voyager 2. Similar solar wind-driven processes could be at work there as well.

More broadly, the findings highlight how space weather can dramatically alter planetary environments, even at vast distances from the Sun.

Why Scientists Want a New Uranus Mission

Despite the progress made with this reanalysis, many questions remain unanswered. Researchers still do not fully understand the precise sequence of physical processes that lead from a solar wind disturbance to intense wave generation and electron acceleration at Uranus.

This uncertainty strengthens the case for a dedicated mission to Uranus, ideally involving an orbiter capable of long-term observations. Such a mission could determine how often extreme radiation events occur, how Uranus’s magnetosphere behaves under quiet conditions, and how its radiation belts evolve over time.

Scientists emphasize that understanding Uranus is not just about one planet. Ice giants are common throughout the galaxy, and insights gained here could help explain the behavior of exoplanetary magnetospheres as well.

A Mystery That May Finally Be Solved

After nearly 40 years, the idea that Voyager 2 caught Uranus during a rare but powerful solar wind storm offers a satisfying and scientifically grounded explanation for one of planetary science’s enduring puzzles. While further exploration is needed to confirm the details, this research shows how revisiting old data with new knowledge can lead to major breakthroughs.

As scientists continue to refine their models and push for future missions, Uranus remains a planet full of surprises—quietly waiting for its next close visitor.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1029/2025GL119311