NASA Has Officially Completed the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope and It’s Almost Ready for Launch

NASA has reached a major milestone with one of its most ambitious space observatories. The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is now fully assembled, marking the end of years of complex engineering and the beginning of its final journey toward launch. The last major step in construction took place on November 25 at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, where technicians successfully joined the telescope’s inner and outer segments inside the agency’s largest clean room.

With construction complete, Roman is moving into its final testing phase. The mission is officially scheduled to launch by May 2027, but teams are confident that it could lift off as early as fall 2026 if everything continues to go smoothly. Once ready, the observatory will travel to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida in the summer of 2026 for launch preparations, before being sent into space aboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket.

A Telescope Built to Answer the Universe’s Biggest Questions

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is designed to be a powerful infrared observatory, capable of surveying enormous portions of the sky with both clarity and speed. Observing from space allows Roman to detect infrared light, which has longer wavelengths than visible light and can travel vast cosmic distances with less interference from dust and gas. This capability gives astronomers a clearer view of distant galaxies, hidden star-forming regions, and planetary systems far beyond our own.

Roman’s wide-field view is one of its defining strengths. While telescopes like Hubble are famous for their detailed images, Roman will combine sharp vision with an exceptionally large field of view, enabling it to map the universe at an unprecedented scale. Scientists expect Roman to dramatically expand our understanding of dark matter, dark energy, galaxy formation, and exoplanets.

Where Roman Will Go and How It Will Get There

After launch, Roman will travel to a stable gravitational location approximately one million miles from Earth, known as the Sun–Earth Lagrange Point L2. This region of space allows the telescope to maintain a consistent orientation relative to the Sun and Earth, which is ideal for long-term observations and thermal stability.

The choice of a Falcon Heavy rocket reflects Roman’s size and complexity. Once deployed, the observatory will begin a carefully planned commissioning period, followed by its five-year primary science mission, during which it will carry out a series of large-scale surveys and targeted observations.

Two Instruments That Power Roman’s Science

Roman carries two primary instruments, each designed to address different scientific goals.

The Wide Field Instrument is the workhorse of the mission. It features a 288-megapixel camera capable of capturing images that cover a patch of sky larger than the apparent size of a full Moon. This instrument alone will allow Roman to collect data hundreds of times faster than the Hubble Space Telescope, ultimately producing around 20,000 terabytes (20 petabytes) of data over the mission’s primary lifetime.

The second instrument is the Coronagraph Instrument, a cutting-edge technology demonstration. Its job is to block out the overwhelming glare of stars so astronomers can directly image faint objects nearby, such as exoplanets and dusty debris disks. Unlike previous direct-imaging efforts that focused mainly on large, young, hot planets, Roman’s coronagraph aims to detect older, colder giant planets in tighter orbits, offering a more complete picture of planetary systems.

The coronagraph will carry out a series of pre-planned observations totaling about three months during the mission’s first year and a half, with the possibility of additional observations later based on feedback from the scientific community.

The Three Core Surveys Driving Roman’s Mission

Roman’s science plan revolves around three major surveys, which together will account for 75% of its primary mission time.

The High-Latitude Wide-Area Survey will image and measure more than one billion galaxies across a vast region of space. By combining imaging and spectroscopy, scientists will study how galaxies formed and evolved over cosmic time, while also mapping the invisible structure of dark matter through its gravitational effects.

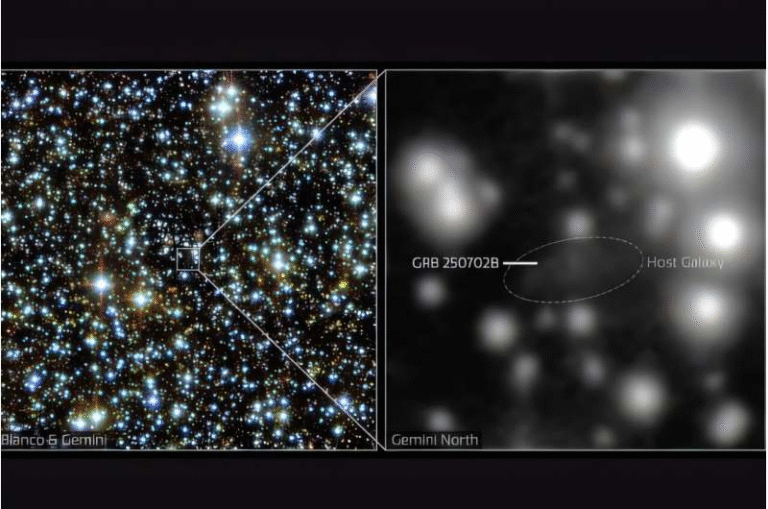

The High-Latitude Time-Domain Survey focuses on change. Roman will repeatedly observe the same areas of the sky to create time-lapse views of cosmic events unfolding over days, months, and years. This approach is especially important for studying dark energy, the mysterious force believed to be driving the accelerating expansion of the universe, and for discovering transient phenomena that may not yet be fully understood.

The Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey looks inward toward the dense heart of the Milky Way. By monitoring hundreds of millions of stars, Roman will search for microlensing events, where the gravity of a foreground object briefly magnifies the light of a background star. These events can reveal exoplanets, rogue planets, and even isolated black holes that would otherwise remain invisible.

A New Era for Exoplanet Discovery

Roman is expected to uncover an astonishing number of worlds beyond our solar system. Over its primary mission, scientists anticipate discovering more than 100,000 exoplanets, including planets located in their stars’ habitable zones and others orbiting far from their parent stars. Microlensing observations will also detect free-floating planets that wander the galaxy without a host star.

In addition to microlensing, the mission’s data will reveal roughly 100,000 transiting planets, expanding our understanding of how planetary systems form and evolve. Together, these discoveries will help answer one of astronomy’s most enduring questions: how common planetary systems like our own really are.

Data for Everyone, Not Just Scientists

One of the defining features of the Roman mission is NASA’s commitment to open science. All of Roman’s data will be made publicly available with no exclusive access period, allowing researchers around the world to analyze observations at the same time. This approach ensures that Roman’s massive data archive can be used for a wide range of investigations, many of which may not even be imagined yet.

In addition to its core surveys, 25% of Roman’s mission time will be allocated to community-driven programs. The first of these, the Galactic Plane Survey, has already been selected, with more to follow based on proposals from astronomers worldwide.

Honoring Nancy Grace Roman’s Legacy

The telescope is named after Dr. Nancy Grace Roman, NASA’s first Chief Astronomer and a key figure in making space-based astronomy a reality. Her vision helped lay the groundwork for missions like Hubble, and Roman continues that legacy by ensuring that vast cosmic datasets are accessible to the entire scientific community.

As Roman moves into final testing, it stands as a symbol of what long-term scientific planning and precision engineering can achieve. Once operational, it is expected to reshape our understanding of the universe, from the nature of dark energy to the abundance of distant worlds, and to provide discoveries that will fuel research for decades to come.

Research reference:

https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.05569