Young Stars Experience Late Growth Spurts That Surprisingly Help Giant Planets Form

Astronomers have long believed that young stars grow steadily and then gradually slow down as they approach maturity. But new research is now challenging that idea, especially for stars that are larger than the Sun. According to a recent study, intermediate-mass stars go through something like an adolescent growth spurt, rapidly gaining mass later in their development. Even more interestingly, this unexpected behavior appears to help gas giant planets like Jupiter form, rather than preventing them.

To understand why this matters, it helps to start with the basics of how stars and planets form.

How Stars and Planets Usually Form

Stars are born inside enormous clouds of cold gas and dust known as molecular clouds. As gravity pulls material inward, a young star begins to take shape at the center. At the same time, leftover gas and dust flatten into a rotating structure called a protoplanetary disk. This disk is the birthplace of planets.

For decades, astronomers have worked with a general model:

- Young stars steadily accrete material from their surrounding disks.

- Over time, radiation from the star pushes some of that material away.

- The disk gradually thins out, the star reaches its final mass, and planet formation slows to a stop.

This model works fairly well for stars similar in mass to the Sun. But when scientists began observing stars that are 1.5 to 4 times more massive, things did not quite add up.

The Puzzle of Intermediate-Mass Stars

Observations of intermediate-mass stars revealed something strange. Instead of slowing down their growth as they aged, these stars appeared to be accreting mass faster later in life. That contradicts standard theory, which predicts that accretion should decline as the disk loses material.

This raised a serious problem. If older stars are accreting more rapidly, their disks would need to start out extremely massive. But disks that are too massive—around 10% or more of the star’s mass—become unstable. They can fragment into clumps and collapse, which actually prevents planets from forming in an orderly way.

So how could these stars both grow rapidly and still allow planets to form?

A Closer Look at Two Types of Young Stars

The new research, titled Evolution of the Accretion Rate of Young Intermediate-mass Stars: Implications for Disk Evolution and Planet Formation, tackled this problem by closely studying two related stellar groups:

- Intermediate-Mass T-Tauri Stars (IMTTSs) – younger, pre-main-sequence stars still in early development.

- Herbig stars – older, hotter stars that IMTTSs evolve into as they approach the main sequence.

By measuring the radiation emitted as material falls onto these stars, researchers were able to calculate how fast each group was growing.

The results were striking.

IMTTSs were found to have accretion rates more than ten times lower than Herbig stars. In some cases, the difference reached a factor of 30. In other words, the stars were growing slowly at first and then suddenly ramping up their growth as they matured.

Why Later Growth Actually Helps Planets Form

At first glance, faster accretion sounds bad for planet formation. After all, if the star is pulling in material more aggressively, wouldn’t that starve the disk?

Counterintuitively, the opposite appears to be true.

Because younger IMTTSs have lower accretion rates, their disks do not need to be extremely massive early on. That keeps them stable and gives planets time to form gradually. Later, when the star evolves into a Herbig star and begins accreting more rapidly, the disk can still survive long enough to support the formation of gas giant planets.

This resolves a long-standing contradiction between observations and theory.

The Role of Heat and Ultraviolet Radiation

So what causes this late-stage growth spurt?

The answer lies in temperature and radiation.

As intermediate-mass stars evolve, their surface temperatures increase dramatically. A star that starts at around 4,900 Kelvin can heat up to more than 9,000 Kelvin as it approaches the main sequence. This temperature increase leads to a massive rise in far-ultraviolet (FUV) radiation.

That FUV radiation plays a crucial role in disk physics.

Magnetism, Ionization, and Faster Accretion

Protoplanetary disks are threaded with magnetic fields, but neutral gas does not interact strongly with magnetism. Ionized gas does.

As FUV radiation increases, it ionizes more gas in the disk. This activates a process known as magnetorotational instability (MRI), which generates turbulence within the disk. That turbulence transports angular momentum outward, allowing gas in the inner regions to fall more easily onto the star.

The result is a higher accretion rate, even though the total disk mass may be declining.

This mechanism provides a physically plausible explanation for why older Herbig stars accrete material faster than their younger counterparts.

Observational Evidence from Modern Telescopes

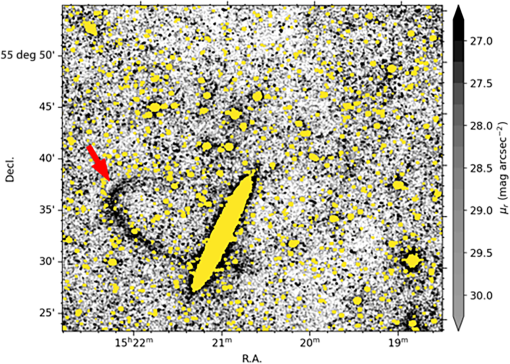

The new model also fits well with what astronomers see through powerful instruments like ALMA and SPHERE on the Very Large Telescope.

Disks around Herbig stars often show spiral arms and complex structures, while disks around IMTTSs usually do not. These spirals were once thought to be caused by gravitational instability or hidden stellar companions. But the new research suggests they may instead be signposts of gas giant planet formation.

In contrast, the calmer disks around younger stars make sense if accretion is still relatively weak at that stage.

Why This Matters for Planet Formation Theory

Gas giant planets are common around intermediate-mass stars, yet classical models struggled to explain how they could form before disks disappeared. This research shows that disks can persist for several million years, even while supporting high accretion rates later on.

That provides enough time for planets like Jupiter to form and grow.

More broadly, the study highlights how stellar radiation feedback plays a central role in shaping disks and planetary systems. It also suggests there may be many young intermediate-mass stars with little or no accretion, quietly waiting before their growth spurt begins.

Expanding Our Understanding of Stellar Evolution

The idea that stars go through an adolescent-like phase may sound surprising, but it builds on well-established physics. Astronomers have known for over a century that hotter stars emit more ultraviolet radiation, and for decades that disk ionization affects accretion.

What this research does is connect those ideas in a new way, showing how they naturally explain observed accretion patterns and planet formation outcomes.

As observations improve and more young stars are studied in detail, this late-stage growth model may become a key piece in understanding how diverse planetary systems emerge across the galaxy.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/ae1a42