Astronomers Are Finally Watching Stars Explode in Real Time With Unprecedented Detail

Astronomers have reached a milestone that many once thought would remain out of reach: they are now directly imaging stellar explosions as they happen, capturing the earliest moments of novae in extraordinary detail. Using advanced observational techniques, researchers have observed how material is expelled from exploding stars in ways that are far more complex, layered, and dynamic than previously assumed. These findings significantly reshape how scientists understand novae and the powerful physical processes behind them.

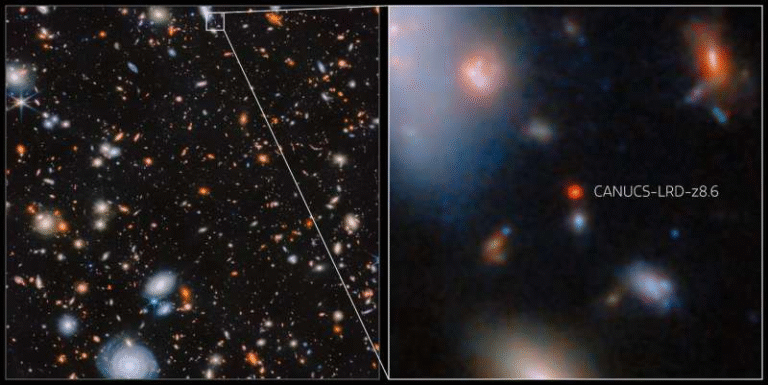

The breakthrough comes from an international research team that used the CHARA Array, a high-resolution optical interferometer operated by Georgia State University and located at the historic Mount Wilson Observatory in California. Their results were published in Nature Astronomy and focus on two novae that erupted in 2021, each behaving in dramatically different ways.

What Exactly Is a Nova?

A nova occurs in a binary star system where a white dwarf—the dense, compact remnant of a dead star—pulls material from a nearby companion star. Over time, this stolen material builds up on the white dwarf’s surface. When conditions become extreme enough, a runaway nuclear reaction ignites, producing a sudden and powerful explosion. Unlike supernovae, novae do not destroy the white dwarf, allowing the process to potentially repeat.

For decades, astronomers believed these explosions were relatively simple: a single, rapid ejection of material expanding outward in all directions. However, the new observations show that this picture is incomplete.

How Interferometry Made This Possible

The key to this discovery is optical interferometry, a technique that combines light from multiple telescopes to achieve the resolution of a much larger instrument. The CHARA Array uses six telescopes arranged along three arms, with their collected light transported through vacuum pipes to a central beam-combining laboratory. This setup allows astronomers to resolve incredibly small details, similar to the technique used to image black holes.

By reacting quickly to newly discovered novae and adjusting observing schedules on short notice, researchers were able to capture images within days of the explosions—something that had never been achieved at this level of clarity.

Nova V1674 Herculis: One of the Fastest on Record

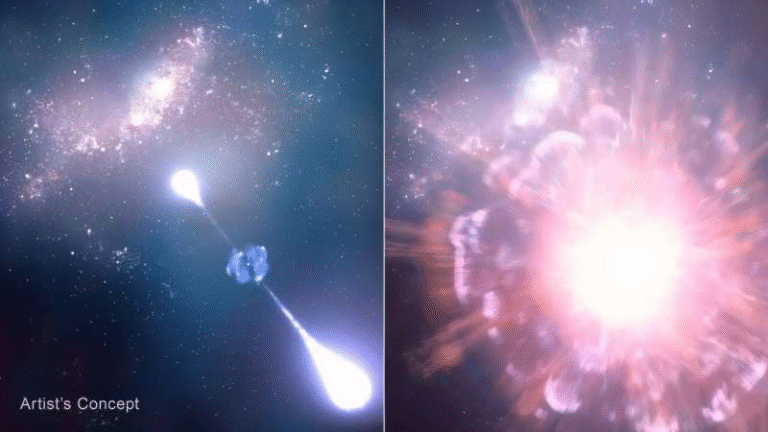

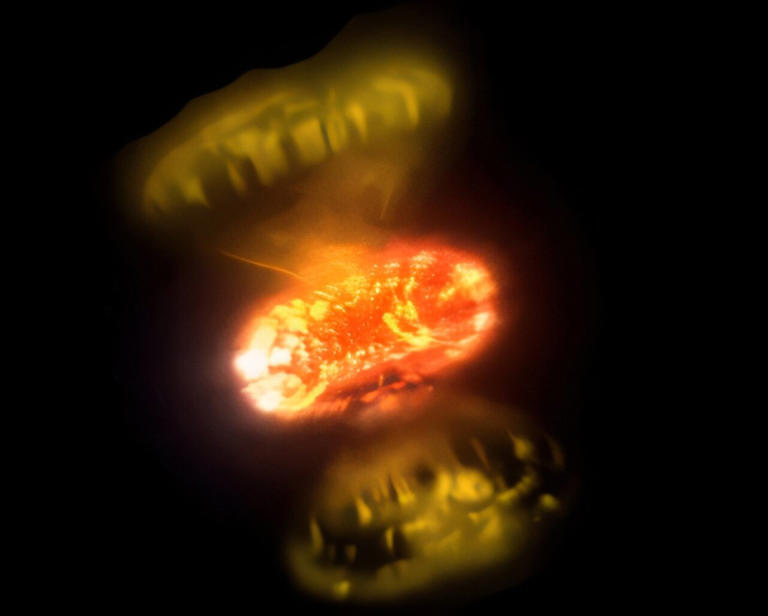

The first object studied was Nova V1674 Herculis, one of the fastest nova eruptions ever observed. It brightened rapidly and faded within just a few days. Images taken approximately 2.2 and 3.2 days after the explosion revealed something entirely unexpected: instead of a single expanding shell, the nova produced two distinct, perpendicular outflows of gas.

These multiple streams of material strongly suggest that the explosion involved interacting ejection events rather than one simple blast. Even more compelling, these structures appeared at the same time NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope detected high-energy gamma rays from the system. This provided direct evidence that gamma-ray emission in novae is produced by shock waves created when different outflows collide.

For years, astronomers suspected such shocks existed, but until now they could only infer them indirectly. These images finally connect the dots between visible ejecta and high-energy radiation.

Nova V1405 Cassiopeiae: A Surprise Delay

The second nova, V1405 Cassiopeiae, followed a very different path. It evolved much more slowly and produced one of the most surprising results of the study. Instead of ejecting its outer layers immediately after the explosion, the system held onto its envelope for more than 50 days.

This delayed ejection had never been directly observed before. When the material was finally expelled, it triggered new shock interactions that again coincided with gamma-ray detections by the Fermi telescope. The finding provides the first clear evidence that some novae experience delayed mass loss, fundamentally challenging the idea that nova eruptions are always quick and impulsive events.

Connecting Images and Spectra

The interferometric images were complemented by spectroscopic observations from major observatories, including Gemini. Spectra track the chemical fingerprints and velocities of ejected gas. As new features appeared in the spectra, they matched the evolving structures seen in the images. This one-to-one correspondence confirmed that astronomers were directly observing how different flows formed, expanded, and collided.

This combination of imaging and spectroscopy offers a far more complete view of nova eruptions than either method alone.

Why Gamma Rays Matter

One of the most important implications of this work is its connection to high-energy astrophysics. In the past 15 years, NASA’s Fermi Large Area Telescope has detected gamma rays from more than 20 novae, establishing these explosions as significant sources of high-energy radiation within our galaxy.

The new observations show exactly how those gamma rays are produced: through shocks formed when fast-moving ejecta crash into slower material. This makes novae valuable natural laboratories for studying shock physics, particle acceleration, and extreme plasma conditions—topics that are relevant far beyond stellar explosions.

Rethinking Nova Eruptions

Taken together, these observations overturn the long-standing assumption that novae are simple, single-stage explosions. Instead, they reveal a wide range of behaviors, including multiple outflows, complex geometries, and delayed envelope release. Each nova appears to follow its own pathway, influenced by factors such as mass transfer rates, binary geometry, and the physical properties of the white dwarf.

This diversity helps explain why novae vary so widely in brightness, duration, and energy output.

Why Novae Are Scientifically Valuable

Novae occupy a unique place in astrophysics. They evolve quickly enough that astronomers can observe major changes over days or weeks, yet they occur close enough to Earth to be studied in detail. This makes them ideal testbeds for understanding nuclear reactions, shock formation, and the interaction between stars in binary systems.

By directly imaging novae in their earliest stages, astronomers can now link theoretical models to real observations with unprecedented confidence.

What Comes Next

Researchers see this work as just the beginning. As interferometric techniques improve and more rapid-response observing campaigns are developed, scientists expect to capture even more novae at critical early moments. Each new observation will help refine models of stellar explosions and improve our understanding of how stars influence their surrounding environments.

Once thought of as relatively simple cosmic fireworks, novae are now emerging as rich, multi-phase events that reveal the inner workings of extreme physics in our galaxy.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02725-1