Cosmic Gas Flows Explain Why the Milky Way Has Two Distinct Chemical Populations

The Milky Way has long puzzled astronomers with one of its most curious traits: stars in our galactic neighborhood fall into two distinct chemical groups, even though they formed in the same galaxy. A new study now offers the clearest explanation yet, showing that this phenomenon is driven not by dramatic galactic collisions, but by the way gas flowed into the Milky Way over billions of years.

This research, published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, provides a detailed look at how galaxies like ours form and evolve, and why their stars carry such surprisingly different chemical fingerprints.

The Mystery of the Milky Way’s Chemical Bimodality

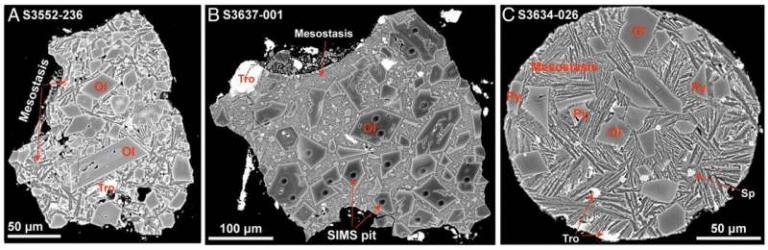

When astronomers analyze stars near the Sun, they often compare the amounts of iron (Fe) and magnesium (Mg) inside them. These two elements are especially useful because they form in different types of supernova explosions and at different times in a galaxy’s history.

What scientists have found is strange: stars cluster into two clear sequences when plotted on a magnesium-to-iron diagram. One group is magnesium-rich and iron-poor, while the other has lower magnesium relative to iron. Even more puzzling, both groups overlap in overall metallicity, meaning they contain similar total amounts of heavy elements.

This pattern, known as chemical bimodality, has been known for years, but its origin has remained controversial.

Simulating Milky Way-Like Galaxies

To tackle this problem, researchers from the Institute of Cosmos Sciences of the University of Barcelona (ICCUB) and the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) turned to advanced cosmological simulations known as the Auriga simulations.

These simulations recreate the formation of galaxies in a virtual universe, following the behavior of dark matter, gas, stars, and chemical enrichment from the early universe to the present day. In this study, scientists examined 30 simulated galaxies that closely resemble the Milky Way in mass and structure.

By tracking how gas flowed into these galaxies and how stars formed over time, the team was able to connect chemical patterns directly to galactic history.

Not All Galaxies Follow the Same Path

One of the most important findings is that chemical bimodality is not inevitable. Some simulated galaxies developed two chemical sequences, while others showed only one. This immediately suggests that the Milky Way’s structure is not a universal template for all spiral galaxies.

In galaxies that did develop bimodality, the researchers identified multiple formation pathways. In some cases, the pattern emerged after bursts of intense star formation followed by quieter periods. In other cases, the key factor was a change in the type of gas flowing into the galaxy from its surroundings.

The takeaway is clear: different evolutionary histories can produce similar chemical outcomes.

The Role of Cosmic Gas Flows

A major conclusion of the study is that metal-poor gas flowing in from outside the galaxy plays a crucial role in shaping the second chemical sequence. This gas comes from the circumgalactic medium (CGM), the vast reservoir of diffuse material surrounding galaxies.

When this relatively pristine gas flows into the galactic disk, it dilutes the existing gas and fuels new star formation. Stars formed during this phase naturally end up with different magnesium and iron ratios, creating a separate chemical population.

This process can happen without any major external disturbance, purely through cosmic gas accretion over time.

Rethinking the Role of Galactic Collisions

For years, many astronomers believed that the Milky Way’s chemical bimodality was caused by a major merger with a smaller galaxy known as Gaia–Sausage–Enceladus (GSE). This ancient collision did leave clear signatures in the Milky Way’s stellar halo.

However, the new simulations show that such a collision is not required to produce chemical bimodality. Some simulated galaxies developed two chemical sequences without experiencing any major merger at all.

This does not mean the GSE event was unimportant, but it suggests that internal processes and gas inflow are far more influential than previously thought when it comes to shaping stellar chemistry.

Star Formation History Leaves a Chemical Imprint

Another key result is the tight connection between star formation history and chemical structure. Galaxies that experienced rapid early star formation tend to produce a magnesium-rich population first. Later, as star formation slows or as new gas enters the system, a second, chemically distinct population can emerge.

The shape and separation of the chemical sequences directly reflect how steadily or erratically a galaxy formed stars over cosmic time. In this way, stellar chemistry acts like a fossil record, preserving clues about events that happened billions of years ago.

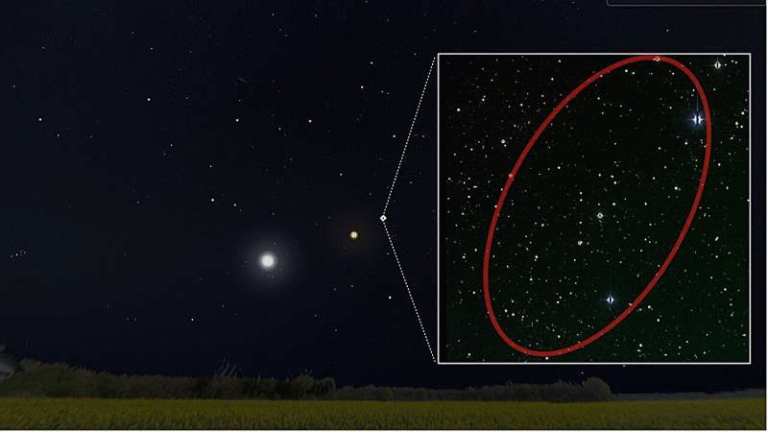

Why Andromeda Looks Different

Interestingly, astronomers have not yet detected clear chemical bimodality in Andromeda, the Milky Way’s nearest large neighbor. The new study offers a possible explanation: Andromeda may simply have followed a different evolutionary path, with smoother gas accretion or a different star formation timeline.

This reinforces the idea that galaxy evolution is diverse, even among systems that look similar today.

What This Means for Future Observations

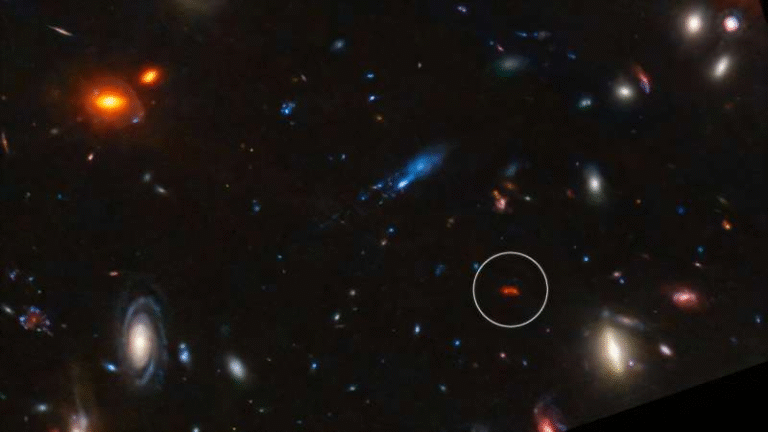

The study also makes predictions that can soon be tested. With observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) already operating, and upcoming missions such as PLATO and Chronos, astronomers will be able to measure stellar ages and chemical compositions with unprecedented precision.

Even more exciting, the next generation of 30-meter-class telescopes will allow researchers to study chemical patterns in external galaxies, not just the Milky Way. This will help confirm whether the diversity seen in simulations truly reflects the real universe.

Understanding Galactic Evolution Through Chemistry

At its core, this research highlights how galactic chemistry is shaped by long-term processes, not just rare catastrophic events. The Milky Way’s double chemical signature emerges from a complex interplay between star formation, supernova explosions, and the steady flow of gas from the cosmic environment.

Rather than being an odd exception, the Milky Way may simply be one example of how different evolutionary routes can lead to similar present-day galaxies.

As astronomers continue to combine detailed observations with powerful simulations, the chemical fingerprints of stars will remain one of the most valuable tools for uncovering the hidden history of our galaxy.

Research paper: https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/545/1/staf1551/8376760