JWST Takes a Deep Look at Omega Centauri in the Search for an Elusive Intermediate-Mass Black Hole

Astronomers have long suspected that a mysterious type of black hole may be hiding in plain sight within our own galaxy, and now the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has taken a major step toward testing that idea. The focus of this latest investigation is Omega Centauri, the largest globular cluster in the Milky Way and the most famous candidate for hosting an intermediate-mass black hole (IMBH). Using JWST’s powerful infrared instruments, researchers set out to look for signs that such a black hole is quietly feeding on surrounding material. What they found did not deliver a dramatic confirmation, but it did significantly narrow the possibilities and push the search into more precise territory.

What Makes Intermediate-Mass Black Holes So Important?

Black holes are usually divided into two well-established categories. On one end are stellar-mass black holes, formed when massive stars collapse, typically weighing a few to a few dozen times the mass of the Sun. On the other extreme are supermassive black holes, containing millions or even billions of solar masses and residing at the centers of galaxies, including the Milky Way.

Between these two groups lies a puzzling gap. Intermediate-mass black holes, expected to weigh anywhere from about 100 to tens of thousands of solar masses, have been predicted by theory but remain frustratingly difficult to confirm. If they exist, they could represent a crucial missing link, explaining how supermassive black holes grow and evolve over cosmic time. Despite numerous candidates, none have yet gained universal acceptance.

Why Omega Centauri Is a Prime Target

Omega Centauri, often abbreviated as Omega Cen, is no ordinary globular cluster. Located roughly 17,000 light-years from Earth, it was once thought to be a single star when viewed with the naked eye. Modern observations have revealed a densely packed system containing around 10 million stars.

Astronomers suspect that Omega Centauri may actually be the remnant core of a dwarf galaxy that was torn apart and absorbed by the Milky Way billions of years ago. If true, it would make sense for it to host a central black hole larger than what is typically expected in a globular cluster. This idea has made Omega Centauri the most closely studied IMBH candidate in our galaxy.

Clues From Stars Moving Too Fast

Black holes themselves cannot be seen directly. Instead, astronomers infer their presence by observing how nearby stars behave under extreme gravity. In the case of Omega Centauri, earlier studies used data from the Hubble Space Telescope to track stellar motions with remarkable precision.

In 2024, researchers analyzed more than 500 Hubble images and measured the velocities of about 1.4 million stars in the cluster. Among them, seven stars near the cluster’s center stood out. These stars were moving so fast that their velocities exceeded the cluster’s escape velocity, yet they remained gravitationally bound. The most straightforward explanation is that a massive unseen object is anchoring them in place.

From these stellar motions, scientists estimated that the central object, if it is a black hole, could have a mass between 39,000 and 47,000 solar masses, with an extreme lower limit of 8,200 solar masses. That firmly places it in the intermediate-mass category.

Turning to JWST for Direct Evidence

While stellar dynamics provide strong indirect evidence, astronomers also look for electromagnetic signals produced when black holes accrete matter. As gas and dust spiral inward, they heat up and emit radiation that telescopes can detect. For this reason, black hole searches often focus on radio, X-ray, and infrared emissions.

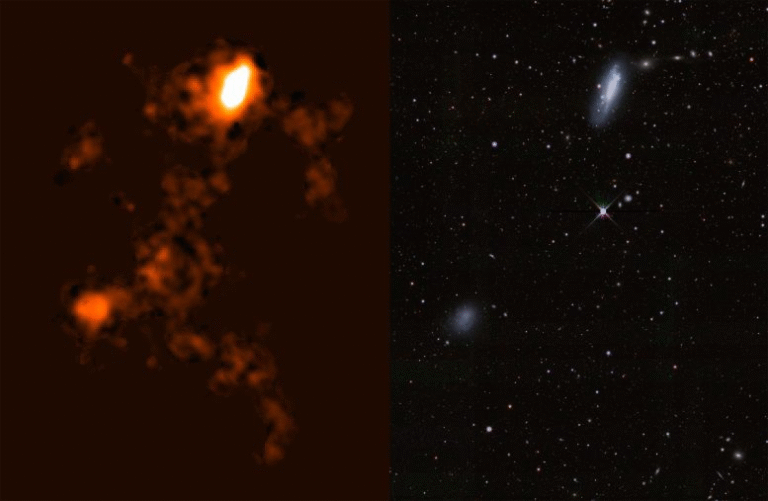

The new study, titled “The Intermediate Mass Black Hole in Omega Centauri: Constraints on Accretion from JWST,” uses data from JWST’s NIRCam and MIRI instruments, collected during observations in 2024. The research team, led by Steven Chen of George Washington University, examined the cluster’s crowded core to see whether any infrared sources could be attributed to an accreting IMBH.

What JWST Found—and Didn’t Find

JWST’s observations were extraordinarily deep and detailed, but they did not reveal a clear, isolated infrared source that could be confidently identified as a feeding black hole. In such a dense stellar environment, this is not entirely surprising. The center of Omega Centauri is packed with stars, sometimes numbering tens of thousands per cubic light-year, making it difficult to separate a faint black hole signal from overlapping starlight.

Although no definitive accretion signature was detected, the absence of strong infrared emission allowed researchers to rule out some possibilities. Specifically, the JWST data exclude the previously suggested lower-mass limit of 8,200 solar masses under standard assumptions about how efficiently black holes accrete matter. The observations instead point toward a mass closer to 20,000 solar masses, assuming very low accretion rates.

In simple terms, if an IMBH exists in Omega Centauri, it appears to be extremely quiet, consuming very little material and emitting almost no detectable radiation.

Why Non-Detections Still Matter

In astronomy, not finding something can be just as informative as finding it. By placing tighter limits on how massive the black hole could be and how much energy it emits, scientists are gradually narrowing the range of viable explanations.

The study emphasizes that flux limits near the cluster’s core depend heavily on how close a potential black hole lies to bright stars. Additionally, mass estimates depend on the assumed accretion model, which is still uncertain for black holes operating at very low feeding rates. These factors make definitive conclusions difficult, even with JWST’s unprecedented sensitivity.

How JWST Fits Into the Bigger Picture

JWST is uniquely suited to this kind of work because of its infrared vision, which can peer through dust and resolve faint sources better than previous space telescopes. Beyond searching for accretion signatures, JWST can also help refine stellar proper motion measurements over long time baselines when combined with decades of Hubble data.

Future observations could reveal new fast-moving stars that are too faint for earlier instruments to detect. If additional stars show extreme velocities near the cluster’s center, the dynamical case for an IMBH would become even stronger.

What This Means for the Search for IMBHs

The results from Omega Centauri reinforce a broader trend in IMBH research. These objects, if they exist, may often reside in environments where accretion is inefficient, making them nearly invisible electromagnetically. That challenges traditional search methods and forces astronomers to rely more heavily on stellar dynamics and long-term monitoring.

Rather than delivering a dramatic “Eureka” moment, progress in this field appears to be happening through incremental elimination of alternatives. Each new constraint removes another piece of uncertainty, bringing scientists closer to understanding whether intermediate-mass black holes truly bridge the gap between stellar and supermassive giants.

For now, Omega Centauri remains one of the best places to look—and JWST has shown that even silence can speak volumes.

Research paper:

Steven Chen et al., The Intermediate Mass Black Hole in Omega Centauri: Constraints on Accretion from JWST, arXiv (2025).

https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2511.20945