NASA Is Running Powerful Moon Landing Tests to Understand How Rocket Plumes Affect Lunar Soil

NASA has begun an ambitious new series of experiments designed to answer a critical question for future Moon missions: what really happens when a spacecraft’s rocket engines blast into the lunar surface during landing and liftoff? The answer matters far more than it might sound. Rocket exhaust doesn’t just disappear into space—it slams into lunar soil, sending dust, rocks, and debris flying at high speeds, potentially threatening landers, scientific instruments, and even astronauts.

To tackle this problem head-on, NASA researchers have launched a long-term plume-surface interaction test campaign at the agency’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. These tests are a key part of the Artemis program, which aims to return humans to the Moon and eventually use lunar missions as a stepping stone toward Mars.

Why Rocket Plumes and Lunar Dust Are a Serious Problem

When a spacecraft lands on the Moon, it doesn’t touch down gently. Its engines fire directly at the ground to slow its descent. On Earth, atmosphere and gravity help tame the chaos. On the Moon, there’s no atmosphere and gravity is much weaker, meaning dust and soil particles can be blasted outward at extreme speeds and over long distances.

This flying debris—known as ejecta—can sandblast landers, damage nearby payloads, coat sensitive instruments, and pose risks to astronauts working on the surface. As NASA plans more frequent and more complex Moon missions, including permanent infrastructure, understanding these physics is essential.

Inside NASA’s Massive Vacuum Chamber

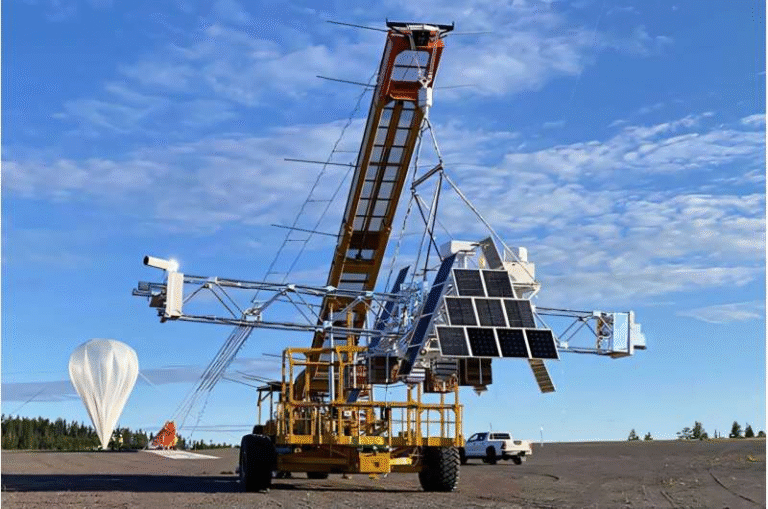

To recreate lunar conditions as accurately as possible, NASA is conducting these tests inside a 60-foot-wide spherical vacuum chamber, one of the largest of its kind. Inside the chamber, researchers can simulate the near-vacuum environment of the Moon and carefully control every variable, from engine thrust to soil composition.

According to the NASA team, this is the most complex plume-surface interaction test series ever attempted inside a vacuum chamber. The goal is not just to observe what happens, but to generate high-quality data that can be used to improve computer models and directly influence spacecraft design.

Two Propulsion Systems, Two Phases of Testing

The campaign is split into two major phases, each using a different propulsion system to simulate spacecraft engine plumes.

The first phase uses an ethane plume simulation system. This system was designed by NASA’s Stennis Space Center in Mississippi and built and operated by Purdue University in Indiana. It can generate up to 100 pounds of thrust, roughly equivalent to the force needed to lift a 100-pound person. While it heats up significantly, it does not burn fuel, making it ideal for controlled early testing.

The second phase is even closer to a real rocket engine. Researchers will use a 14-inch, 3D-printed hybrid rocket motor developed at Utah State University and recently tested at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama. This motor produces around 35 pounds of thrust and combines solid propellant with a stream of gaseous oxygen to create a hot, high-energy exhaust plume. While smaller than an actual lunar lander engine, it captures many of the same physical effects.

Simulating the Moon’s Harsh Surface

Both propulsion systems are fired into a specially prepared container of simulated lunar soil. The bin measures about six and a half feet in diameter and one foot deep and is filled with a regolith simulant known as Black Point-1. This material was chosen because it has jagged, cohesive properties similar to real lunar regolith, making it particularly challenging and realistic.

By testing at different engine heights above the surface, NASA can study a wide range of landing scenarios—from small robotic landers to large human-rated spacecraft.

Advanced Instruments Capture Every Detail

Each test lasts only about six seconds, but an impressive array of instruments captures what happens during that brief window. High-speed cameras, including versions of the specialized imaging system used during Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost Mission-1 landing, record the interaction between the plume and the surface in extreme detail.

Researchers measure:

- Crater formation and erosion

- Speed and direction of ejected particles

- Shape and behavior of the exhaust plume

- How debris interacts with nearby structures

This data will help scientists understand not just what happens, but why it happens—an essential step toward improving predictive models.

Supporting Artemis and Commercial Moon Landers

One of the most important outcomes of this campaign is its value to NASA’s commercial partners. Companies developing human landing systems for Artemis missions, starting with Artemis III, will be able to use this data to refine their designs and improve safety margins.

As NASA prepares to land astronauts near previously unexplored regions of the Moon, including the south polar area, understanding plume effects becomes even more critical. The Moon’s surface isn’t uniform, and different soil properties can dramatically change how debris behaves during landing.

Designed for the Moon—and Beyond

Although the current focus is the Moon, this test setup was designed with flexibility in mind. The lunar soil simulant can be replaced with a Mars-like material, and the vacuum chamber’s pressure can be adjusted to simulate the thin Martian atmosphere rather than a near-total vacuum.

This means the same facility could one day help prepare for human missions to Mars, where plume-surface interaction will also be a major challenge, especially for large, heavy landers.

Why Plume-Surface Interaction Research Matters

Plume-surface interaction is one of the less glamorous but most critical areas of spaceflight engineering. Past missions have shown that dust can interfere with sensors, degrade solar panels, and reduce the lifespan of surface hardware. As NASA moves toward long-term exploration and sustained lunar presence, these issues become mission-critical rather than theoretical.

By combining ground testing, advanced imaging, and computational modeling, NASA is building a much clearer picture of how spacecraft and planetary surfaces interact under extreme conditions.

Looking Ahead

This test campaign will continue through the spring of 2026, involving multiple NASA centers, universities, and commercial partners. The sheer volume of data expected from these tests is described by researchers as a “treasure trove” that will influence spacecraft design for years to come.

For now, the Moon remains the primary focus—but the lessons learned here will shape how humans land on other worlds in the future.

Research reference:

https://www.mdpi.com/2226-4310/11/6/439