Spending Less on Food Can Lead to Healthier Diets With a Much Smaller Climate Footprint

Eating well is often seen as a luxury—something that costs more money and, in many cases, comes with a higher environmental price tag. A major new global study challenges that belief in a very direct way. According to this research, healthy diets can actually be cheaper and produce far fewer greenhouse gas emissions than what most people currently eat, and in many cases, spending less money is a surprisingly effective way to eat more sustainably.

The study, published in Nature Food in 2025, brings together data on food prices, nutrition, availability, and climate impact from nearly every country in the world. Its findings have important implications not just for individuals trying to eat better, but also for governments and organizations working to cut emissions without worsening food insecurity.

A Global Study With a Simple but Powerful Question

The research was led by scientists from the Gerald J. and Dorothy R. Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University, along with international collaborators. Their core question was straightforward: What foods can meet basic nutritional needs at the lowest possible cost and with the lowest possible greenhouse gas emissions?

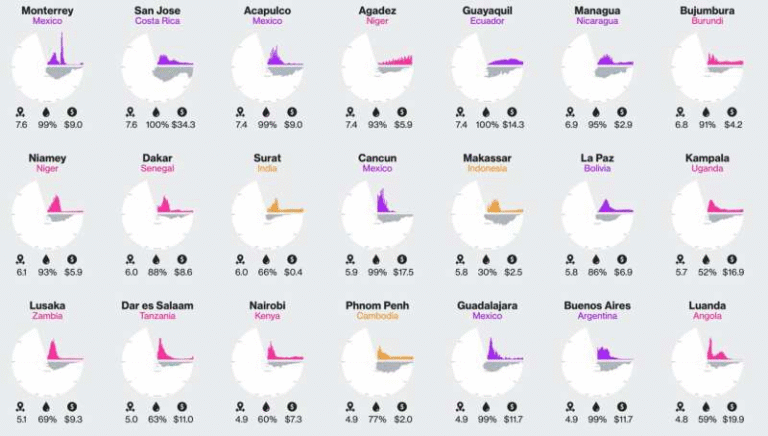

To answer this, the researchers examined 171 countries using data from 2021. They focused on foods that are locally available, rather than idealized global diets that may not reflect what people can actually buy in their own countries.

The team analyzed three major aspects of each food item:

- Price and availability in each country

- How commonly the food is consumed within national diets

- Average greenhouse gas emissions associated with producing that food

Using this information, they created several different diet scenarios and compared them to what people typically eat today.

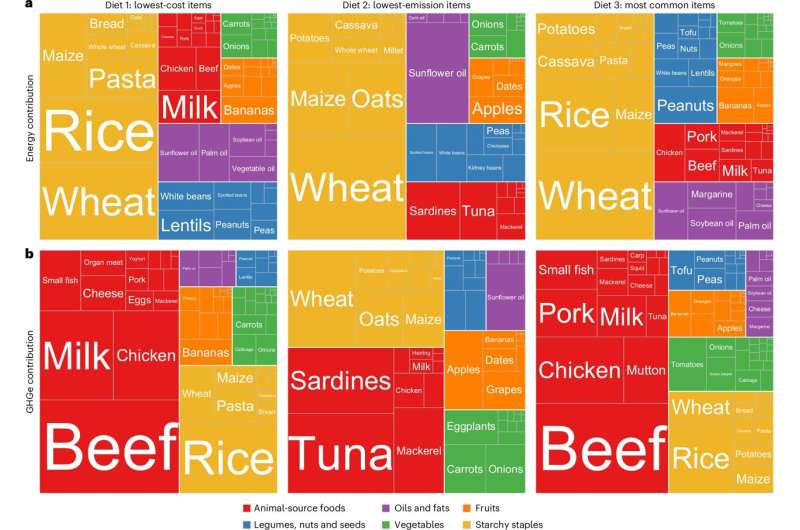

Understanding the Five Diet Scenarios

The researchers modeled five versions of healthy diets, all of which met established nutritional requirements based on the Healthy Diet Basket framework used by the United Nations and national governments.

The most important scenarios included:

- A lowest-cost healthy diet, built entirely from the cheapest foods that meet nutritional needs

- A lowest-emissions healthy diet, designed to minimize climate impact regardless of price

- A most commonly consumed healthy diet, based on foods people already eat most often

- Three additional variations that blended commonly eaten foods with healthier or cheaper options

This approach allowed the researchers to compare affordability, emissions, and real-world eating patterns side by side.

The Numbers That Changed the Conversation

When the researchers compared the diets, the results were striking.

In 2021, a healthy diet made from the most commonly consumed foods emitted an average of 2.44 kilograms of CO₂-equivalent emissions per person per day and cost about $9.96 per day globally.

In contrast:

- The lowest-emissions healthy diet produced just 0.67 kilograms of emissions and cost $6.95 per day

- The lowest-cost healthy diet cost only $3.68 per day and emitted 1.65 kilograms of emissions

- A blended diet combining common foods with lower-cost healthy choices cost around $6.33 per day and emitted 1.86 kilograms of emissions

In every case, these alternatives were both cheaper and more climate-friendly than the typical healthy diet people currently follow.

Why Cheaper Foods Often Mean Lower Emissions

One of the study’s most important findings is that, within most food groups, less expensive foods tend to generate fewer greenhouse gas emissions. This happens for several reasons.

Cheaper foods often require:

- Less intensive energy use

- Fewer synthetic inputs like fertilizers

- Less land-use change

As a result, simply choosing the lower-priced option within a food group—such as beans instead of premium processed plant foods—can significantly reduce a diet’s climate impact.

This pattern held true across most food categories, including fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds, oils, and fats.

Where Tradeoffs Start to Appear

While cheaper usually means greener, the study identified important exceptions, especially at the extreme low-cost or low-emissions ends of the spectrum.

Animal-Sourced Foods

Among animal-based foods, milk often emerged as the least expensive option and had much lower emissions than beef and other meats. However, some small fish, such as sardines and mackerel, showed even lower emissions per calorie, though they were slightly more expensive than milk.

This means that at very low emission targets, the cheapest option is not always the most climate-friendly one.

Starchy Staples

A similar tradeoff appeared among staple grains. Rice is frequently the cheapest staple food in many countries, but it has higher emissions than wheat or corn. The reason is methane released from flooded rice paddies, which significantly increases rice’s climate footprint.

Wheat and corn are often slightly more expensive but generate fewer emissions overall.

What This Means for Consumers

For everyday shoppers, the takeaway is refreshingly simple: frugality can be a guide to sustainability.

Most people can lower their dietary emissions by:

- Choosing less expensive foods within each food group

- Reducing reliance on high-emission meats like beef

- Favoring legumes, grains, milk, and lower-impact fish where available

These choices don’t require specialty products or premium “eco-friendly” labels. They rely on foods that are already widely accessible.

Implications for Policy and Food Systems

The findings also matter at a much larger scale. Governments and international organizations are under pressure to cut food system emissions without increasing hunger or food costs.

This study suggests that climate and nutrition goals do not have to conflict. Policies that:

- Support access to affordable, healthy foods

- Encourage lower-emission staples

- Invest in methane reduction for rice and dairy production

could improve public health while reducing environmental harm.

However, the researchers also note a serious challenge: billions of people worldwide still cannot afford even the cheapest healthy diets, highlighting the need for broader economic and food system reforms.

Why This Study Stands Out

What makes this research especially valuable is its global scope and real-world focus. Instead of promoting idealized diets, it works within the constraints of what people can actually buy, in their own countries, at local prices.

It also directly challenges the assumption that climate-friendly eating is a luxury reserved for wealthy consumers. In reality, the study shows that lower-cost diets often align naturally with lower emissions, with only a few key exceptions.

A Clear Message Moving Forward

The overall message is hard to ignore: healthy eating does not have to be expensive, and it does not have to harm the planet. In many cases, spending less on food can deliver better outcomes for both personal health and the climate.

As food prices rise and climate concerns grow, this research provides a practical, evidence-based foundation for rethinking how we approach everyday eating—one grocery choice at a time.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-025-01270-4