Deep-Sea Mining Test Linked to a 37% Drop in Seafloor Animals Raises Fresh Environmental Questions

A major new scientific study has delivered one of the clearest pictures yet of how deep-sea mining affects life on the ocean floor—and the results are hard to ignore. Researchers found that a test involving a modern deep-sea mining machine led to a 37% decrease in the abundance of animals living in the sediment directly disturbed by the machine. This makes the project the largest and most detailed investigation so far into how industrial-scale deep-sea mining impacts seafloor ecosystems.

The research focused on a region targeted for future seabed mining and aimed to do something scientists have struggled with for decades: separate the effects of mining from the deep sea’s own natural ups and downs. To achieve this, the team collected baseline biodiversity data, tracked natural changes over time, and then measured what happened after a mining test took place.

Where the Study Took Place and Why It Matters

The study was carried out in the Clarion–Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a vast abyssal region of the Pacific Ocean that lies about 4 kilometers below the sea surface. This area is of intense global interest because it contains enormous quantities of polymetallic nodules—potato-sized mineral deposits rich in metals such as manganese, nickel, cobalt, and copper. These metals are considered important for batteries, renewable energy technologies, and electric vehicles.

At the same time, the CCZ is home to an unexpectedly rich and poorly understood ecosystem. Much of the life here grows slowly, reproduces infrequently, and may take decades—or longer—to recover from disturbance. That makes understanding mining impacts especially urgent as commercial operations move closer to reality.

How the Research Was Conducted

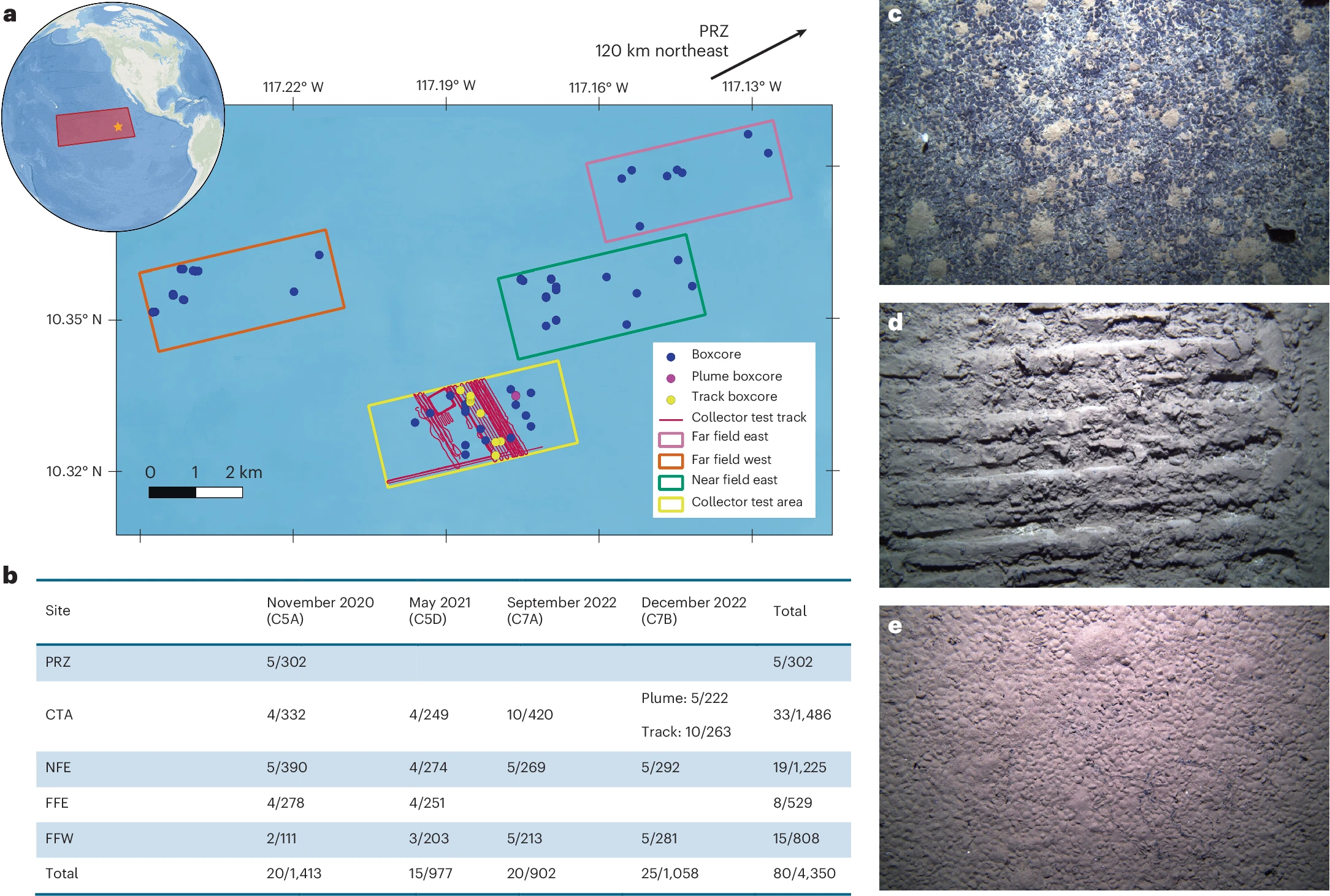

The project was led by scientists from the Deep-Sea Research Lab at the Natural History Museum, with co-leads from the University of Gothenburg and the National Oceanography Centre. The work took five years to complete and involved more than 160 days at sea, followed by three years of detailed laboratory analysis.

To ensure accurate results, researchers carefully designed the study to account for natural variation across space and time. They sampled:

- Control sites that were never disturbed

- Areas directly impacted by the mining machine’s tracks

- Regions affected only by the sediment plume, roughly 400 meters away from the mining path

To precisely sample inside the mining tracks, the team used a Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) guided from a research ship operating far above the seafloor.

What the Scientists Found

Across four expeditions, researchers collected 4,350 macrofaunal animals from sediment samples. Macrofauna are animals visible to the naked eye, typically ranging from 0.3 millimeters to 2 centimeters in size. These included polychaete worms, crustaceans like isopods, amphipods, and tanaids, and mollusks such as snails and clams.

From these samples, scientists identified 788 distinct species, many of which are new to science. DNA analysis played a key role, as most deep-sea species have never been formally described.

The most striking result was the 37% drop in macrofaunal density within the mining tracks. In contrast:

- Animal numbers at control sites either increased or remained stable

- Areas affected only by the sediment plume showed no overall loss in abundance

However, plume-impacted areas did show changes in which species dominated, suggesting subtle but meaningful ecological shifts.

Biodiversity Changes Beyond Animal Numbers

The study didn’t stop at counting animals. It also examined biodiversity in detail. In areas directly disturbed by the mining machine:

- Species richness fell by 32%

- A smaller number of species became more dominant

- Overall community structure became more patchy and variable

Interestingly, when biodiversity was measured using methods that are independent of sample size, overall diversity appeared unchanged. This highlights how different metrics can tell very different stories, and why large, carefully designed studies are so important.

Scientists also noted that communities were more unevenly distributed after the mining test—a pattern consistent with disturbance studies in shallow marine environments and on land.

Accounting for Natural Ocean Changes

One of the most valuable aspects of this research is that it explicitly accounted for strong natural variability in the deep sea. The team suggests that some of this variation may be linked to large-scale climate patterns such as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, which can influence food supply to the deep ocean.

By including long-term control data, the researchers were able to confidently attribute the observed declines in animal abundance and species richness to the mining activity itself—not just natural fluctuations.

Why This Study Is So Important

According to the scientists involved, this research sets a new benchmark for environmental studies related to deep-sea mining. The scale of sampling, the taxonomic detail, and the integration of molecular data make it one of the most comprehensive assessments ever conducted in the CCZ.

The findings provide hard, quantitative evidence that even a single industrial mining test can significantly alter abyssal ecosystems. This information is expected to play a key role in discussions led by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which is responsible for regulating mining activities in international waters.

The Bigger Picture: Deep-Sea Mining and Biodiversity Risk

Deep-sea ecosystems are known for their slow recovery rates. Polymetallic nodules themselves can take millions of years to form, and many animals rely on them as habitat. Removing nodules and disturbing sediments could therefore lead to long-lasting or irreversible ecological changes.

The researchers stress that we still know very little about the biodiversity within the large protected areas designated by the ISA across the CCZ. Without better knowledge of what lives there, it remains difficult to predict how much biodiversity could be lost if mining proceeds at scale.

What Comes Next

The team behind the study emphasizes that this work was done to make vital biodiversity data publicly available. Their goal is to inform everyone involved in deep-sea mining decisions—from regulators and industry to scientists and environmental organizations.

Future research will need to focus on:

- Long-term recovery of disturbed areas

- Biodiversity within protected zones

- Cumulative impacts of repeated mining operations

As interest in deep-sea mining continues to grow, studies like this offer a clearer view of what is truly at stake beneath the waves.

Research paper:

Impacts of an industrial deep-sea mining trial on macrofaunal biodiversity, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2025)

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-025-02911-4