Wildfire Smoke Reaching the Upper Atmosphere Could Have a Bigger Impact on Earth’s Climate Than We Thought

Wildfires are no longer just ground-level disasters that burn forests, destroy homes, and degrade air quality. New research shows that some of the most intense fires on Earth are powerful enough to influence the upper layers of the atmosphere, potentially altering how our planet absorbs and releases heat. Scientists now believe this overlooked process could have meaningful consequences for Earth’s climate system, and it’s something current climate models do not fully account for.

How Extreme Wildfires Create Their Own Weather

Certain large and intense wildfires generate so much heat that they form their own thunderstorms, known as pyrocumulonimbus storms. These fire-driven storms act like giant chimneys, pushing massive amounts of smoke high into the sky—sometimes as far as 9 to 10 miles above Earth’s surface. That places the smoke in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere, a region of the atmosphere that is typically calm and thin.

Once smoke reaches this height, it behaves very differently than smoke closer to the ground. Instead of dispersing quickly, these high-altitude smoke plumes can linger for weeks or even months, traveling vast distances and interacting with sunlight in ways scientists are still trying to fully understand.

A Rare Opportunity to Study Fresh High-Altitude Smoke

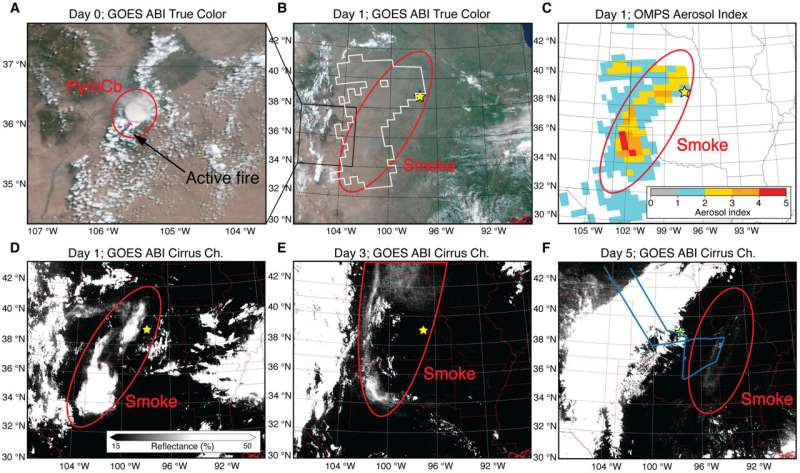

An atmospheric science team from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) took advantage of a rare opportunity to directly observe freshly lofted wildfire smoke. The event occurred after a June 2022 wildfire in New Mexico, which produced a powerful pyrocumulonimbus storm that injected smoke into the uppermost troposphere.

To study this plume, researchers used NASA’s ER-2 high-altitude research aircraft, a specialized plane capable of flying at extreme altitudes. With help from geostationary satellite imagery, the team tracked the smoke plume and flew directly through it just five days after the fire, allowing them to observe the particles while they were still relatively young.

This is significant because most previous measurements of high-altitude wildfire smoke were taken weeks after formation, when the smoke had already aged and changed.

What the Scientists Found Inside the Smoke Plume

Inside the plume, researchers observed something unexpected: unusually large aerosol particles. These smoke particles measured around 500 nanometers in diameter, roughly twice the size of typical wildfire smoke aerosols found at lower altitudes.

To understand why these particles were so large, the team collaborated with modeling experts from Colorado State University. Their analysis showed that efficient particle coagulation—the process where particles collide and stick together—was likely responsible.

In the upper troposphere, air mixes very slowly. This allows smoke particles to remain densely packed for longer periods, increasing the chances that they collide and merge. The result is fewer particles overall, but each one is much larger than normal.

Why Particle Size Matters for Climate

Aerosol particle size plays a crucial role in how smoke affects Earth’s energy balance. Smoke particles can either absorb sunlight, which warms the surrounding air, or scatter sunlight back into space, which has a cooling effect.

The Harvard-led study found that these large, high-altitude smoke particles were especially effective at enhancing radiative cooling. Compared with smaller smoke particles at lower altitudes, the larger aerosols increased outgoing radiation by 30 to 36 percent in that region of the atmosphere.

This is a substantial effect—and one that is not currently included in most climate models.

Why This Matters for Climate Models

Climate models are essential tools for predicting future warming, changes in weather patterns, and long-term climate risks. However, these models typically assume wildfire smoke particles are relatively small and short-lived. The new findings suggest that assumption may be incomplete, especially as wildfires become more frequent and intense worldwide.

By underestimating particle size and persistence at high altitudes, models may also be underestimating wildfire-related cooling effects, as well as missing secondary impacts on atmospheric circulation.

Possible Effects on Weather and Atmospheric Circulation

Beyond temperature changes, high-altitude smoke can also influence atmospheric dynamics. When smoke absorbs sunlight, it can locally heat the surrounding air. This heating has the potential to alter wind patterns, shift jet streams, and influence broader weather systems.

Scientists caution that it is still too early to say exactly how these processes will unfold, but the possibility alone highlights how interconnected wildfires and climate systems have become.

Implications for Ozone and Atmospheric Chemistry

Another area of concern is how wildfire smoke interacts with atmospheric composition, particularly the stratospheric ozone layer, which protects life on Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation. Smoke particles can host chemical reactions on their surfaces, potentially influencing ozone chemistry in ways that are not yet fully understood.

As more smoke reaches higher altitudes, understanding these chemical interactions becomes increasingly important.

Wildfires and Climate Change: A Feedback Loop

Wildfires are both a consequence of climate change and a driver of further climate effects. Rising temperatures, prolonged droughts, and shifting precipitation patterns make forests more flammable. In turn, larger and more intense fires release vast amounts of carbon dioxide, aerosols, and heat into the atmosphere.

The discovery that wildfire smoke can significantly alter Earth’s energy balance at high altitudes adds another layer to this feedback loop. It suggests that fires don’t just affect regional air quality or short-term weather—they may play a role in global climate dynamics.

Why High-Altitude Observations Are So Rare

Directly measuring smoke in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere is extremely challenging. Specialized aircraft, precise satellite tracking, and coordinated research teams are required. That’s why studies like this one are rare—and why their findings carry so much weight.

The ability to capture fresh smoke just days after a fire provides insights that simply aren’t possible with older, more dispersed plumes.

What Comes Next for Researchers

Scientists emphasize that this study represents an important step, not a final answer. More observations are needed across different fires, regions, and seasons to understand how common these large particles are and how long their effects last.

As wildfires continue to intensify globally, incorporating these findings into climate models will be essential for more accurate predictions of Earth’s future climate.

Research Paper Reference:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adw6526