Melting Glaciers May Be Quietly Increasing Earthquake Activity in Mountain Regions

Scientists have long suspected that changes on Earth’s surface can influence what happens deep underground. Now, a new study suggests that climate change–driven glacier melt may be directly linked to increased earthquake activity in high mountain regions, offering fresh insight into how a warming planet could reshape seismic hazards.

The research focuses on the Mont Blanc Massif, one of the highest and most complex mountain regions in Europe, located along the border between France and Italy. This area is not only famous for its dramatic peaks and glaciers but is also one of the most seismically active zones in the Alps. By examining years of earthquake data alongside climate-driven changes in snow and ice, researchers have uncovered evidence that melting glaciers may be playing a role in triggering earthquakes beneath the mountains.

A First-of-Its-Kind Observational Link

The study, published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, is the first to present direct observational evidence connecting climate-change-induced glacier melt to increased seismic activity. While scientists have previously noted seasonal patterns in earthquakes and speculated about possible causes, this research goes a step further by tying those patterns specifically to global warming and glacial meltwater.

The research team analyzed 15 years of seismic activity, compiling a detailed catalog of 12,303 earthquakes recorded between 2006 and 2022. Their focus was the Grandes Jorasses, a prominent peak within the Mont Blanc Massif. This region already had a reputation for frequent small earthquakes, making it an ideal natural laboratory for studying how environmental changes might affect seismic behavior.

What stood out in the data was not just the presence of earthquakes, but how their timing and location aligned with glacier melt patterns.

Seasonal Earthquakes and Meltwater Patterns

For years, scientists have observed that the Mont Blanc region experiences more earthquakes in late summer and early autumn, when snow and ice melt reaches its peak, and fewer tremors during winter, when glaciers are frozen solid. This seasonal cycle alone hinted that surface processes might be influencing seismic activity.

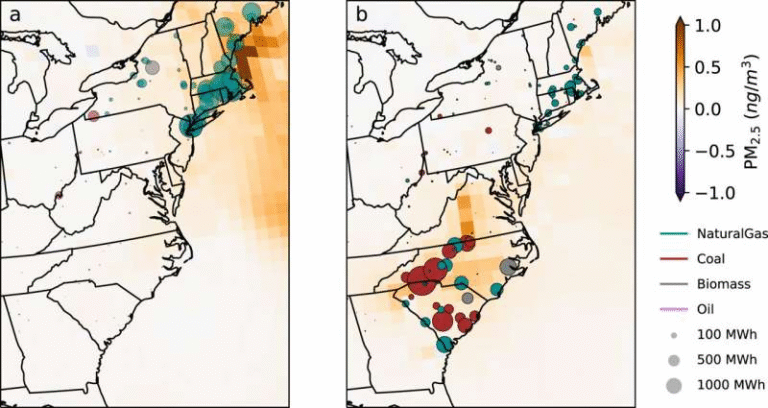

The new study confirms and expands on this idea. The earthquakes were found to cluster along a known shear zone—a fracture zone in the rock—near the Mont Blanc Tunnel, a major transportation link between France and Italy. Measurements of water temperature, conductivity, and isotopic composition in this area point to a strong presence of young surface meltwater, meaning water that recently originated from melting snow and glaciers.

In simple terms, the places where meltwater flows underground most efficiently are also the places where earthquakes occur most frequently.

How Meltwater Can Trigger Earthquakes

The underlying mechanism proposed by the researchers centers on pore pressure—the pressure exerted by fluids trapped within the tiny spaces in rock.

When glaciers melt, large volumes of water flow across the surface. Some of this water doesn’t just run downhill into rivers; it seeps into cracks, fractures, and porous rock beneath the glacier. As this meltwater moves downward through the Earth’s crust, it fills microscopic pores and fractures, increasing pressure along fault zones.

Faults are surfaces where blocks of rock slide past one another. Many faults contain gouge, a soft, crushed material formed as rocks grind together. When fluids enter this material, they can reduce friction, making it easier for faults to slip. Even small changes in stress or pressure can be enough to trigger an earthquake, especially in regions where faults are already close to failure.

The study suggests that climate-driven meltwater is altering underground stress conditions, effectively nudging faults into motion.

The 2015 Heat Wave as a Turning Point

One of the most striking findings relates to a major heat wave in 2015. That year, the Mont Blanc region experienced unusually high temperatures, leading to exceptionally intense glacier melt.

Following this event, the earthquake catalog shows a clear and sustained increase in seismic activity, both in the number of earthquakes and in their magnitude. Importantly, this wasn’t just a short-lived spike. Elevated seismic activity continued in the years after 2015, suggesting a lasting change in the system.

To better understand this shift, the researchers turned to numerical modeling. Their models showed that from 2015 onward, higher-altitude regions of the Mont Blanc Massif and nearby Swiss Alps experienced increased earthquake activity. These areas had previously remained frozen for much of the year, but warming temperatures allowed meltwater to penetrate regions that had once been sealed by ice and permafrost.

A Delayed Underground Response

Another key discovery was the presence of a time delay between surface melting and earthquake occurrence.

Shallow earthquakes tended to correlate with meltwater runoff from the previous year, while deeper earthquakes aligned with runoff from two years earlier. This delay makes sense when considering how long it takes water to travel through rock and influence pressures at depth.

In other words, today’s glacier melt may be contributing to earthquakes months or even years later, highlighting the long-term geological consequences of ongoing climate change.

Skepticism and Scientific Debate

Not all scientists are fully convinced, and the study acknowledges existing uncertainties. Some seismologists question whether surface meltwater can consistently reach depths where significant fault movement occurs. Meltwater begins at the surface, and the Earth’s crust is complex, with many barriers that can limit fluid flow.

Still, even skeptical experts agree that changes in stress regimes can trigger faults under the right conditions. The growing body of observational evidence from the Mont Blanc region suggests that, at least in some geological settings, glacier melt is capable of influencing seismic activity.

What This Means for Mountain Communities

The implications extend far beyond the Alps. Glaciers around the world are melting at unprecedented rates, from the Himalayas to the Andes and the Rockies. Many of these regions are already tectonically active and home to vulnerable mountain communities.

If glacier melt does increase seismic hazard, even modestly, it could mean more frequent small earthquakes and a higher likelihood of damaging events in some regions. While the earthquakes observed in this study were mostly small, they offer a warning sign of how interconnected Earth’s systems truly are.

Experts emphasize the importance of careful monitoring. Mapping the locations and depths of small earthquakes can help identify which faults are becoming active, potentially improving earthquake preparedness and risk assessments in glaciated regions.

The Bigger Picture: Climate Change and the Solid Earth

This research adds to a growing understanding that climate change doesn’t just affect the atmosphere, oceans, and ecosystems—it also interacts with the solid Earth. Changes in ice load, water distribution, and temperature can subtly reshape stress patterns in the crust.

While climate change is unlikely to cause large, catastrophic earthquakes on its own, it may act as a trigger or amplifier in regions already prone to seismic activity. As glaciers continue to retreat, scientists expect these interactions to become more visible and better understood.

Looking Ahead

The findings from the Mont Blanc Massif open the door to new research questions. How widespread is this phenomenon? Which geological settings are most vulnerable? And how should seismic hazard models account for a warming climate?

As global temperatures rise and glaciers shrink, the answers to these questions will become increasingly important. What happens on the surface of our planet, it turns out, can echo deep beneath our feet.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2025.119372