How Pond Depth, Light, and Water Layers Shape Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Small ponds may look quiet and harmless, but new research shows they can play an outsized role in releasing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. A recent scientific study from Cornell University takes a close look at how subtle differences in pond depth, light penetration, and water stratification can dramatically change how much carbon dioxide (CO₂) and methane (CH₄) ponds emit. The findings highlight why ponds, despite often being ignored in climate models, deserve much more attention.

The study focused on two ponds in central New York: Mud Pond and Texas Hollow Pond. At first glance, these ponds appear remarkably similar. They are close in size, located in the same region, and experience similar weather conditions. However, they differ slightly in depth and in how light moves through the water. These small differences turned out to have big consequences for greenhouse gas emissions.

The research was led by Meredith Holgerson, an associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Cornell University. After arriving at Cornell in 2020, Holgerson began searching for ponds that could help answer a long-standing question in freshwater science: why do ponds emit such high levels of greenhouse gases, and what controls those emissions?

By 2021, her team identified Mud Pond and Texas Hollow Pond as ideal natural laboratories. What followed was a detailed, multi-year investigation into how carbon is stored, transformed, and released from these small water bodies.

Why Ponds Matter More Than We Think

Ponds are often overlooked in global carbon budgets. Compared to large lakes or oceans, they cover a relatively small area. However, scientists increasingly recognize ponds as biogeochemical hotspots. This means that, relative to their size, they store large amounts of carbon in their sediments and release significant quantities of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

Both Mud Pond and Texas Hollow Pond fit this pattern. The researchers found that each pond held substantial carbon reserves in its sediments while simultaneously emitting high levels of CO₂ and methane. In fact, the methane bubbling observed in Mud Pond ranks among the highest ever measured in ponds or lakes.

Carbon Dioxide: A Surprising Difference

One of the most striking findings of the study involved carbon dioxide emissions. Texas Hollow Pond is only a little over one meter deeper than Mud Pond. Yet, despite this modest difference, Texas Hollow emitted more than twice as much CO₂ as Mud Pond.

Initially, the researchers expected Mud Pond to release more carbon dioxide. Mud Pond has higher oxygen levels throughout much of the water column, which usually promotes processes that generate CO₂. Instead, the opposite happened.

This unexpected result pointed to the importance of light availability and biological activity. Mud Pond allows sunlight to penetrate deeper into the water, supporting the growth of aquatic plants. These plants actively absorb carbon dioxide during photosynthesis, reducing the amount of CO₂ that escapes into the air.

Methane: When Less Stratification Means More Emissions

Methane emissions told a different and equally surprising story. Methane can escape ponds in two main ways: slowly diffusing from dissolved methane in the water, or rapidly bubbling up from sediments in a process known as ebullition.

The researchers initially hypothesized that stronger water stratification would lead to higher methane emissions. Stratification occurs when water forms distinct layers of different temperatures, often trapping gases in deeper layers.

Texas Hollow Pond showed much stronger stratification than Mud Pond. Yet, Mud Pond produced nearly twice as much methane bubbling from its sediments. Even more unexpected, the amount of methane released through diffusion was nearly identical in both ponds.

This contradicted earlier findings from other pond studies, where stronger stratification typically led to greater methane buildup and release.

Light, Plants, and the Methane Puzzle

To explain these results, the researchers looked beyond stratification alone. Mud Pond’s weaker stratification allows light to reach the bottom, encouraging dense plant growth throughout the pond. While these plants absorb CO₂ when alive, they also create a different problem.

When aquatic plants die, they sink into the sediment. As this organic matter decomposes in low-oxygen conditions, it fuels methane production. The result is an increase in methane bubbles rising from the pond floor.

In contrast, Texas Hollow Pond has low oxygen levels near the bottom, which also supports methane production. However, its strong stratification traps some of that methane in deeper layers, preventing it from escaping into the atmosphere as easily.

A “Goldilocks” Effect in Pond Emissions

The researchers now suspect that the relationship between stratification and greenhouse gas emissions follows a Goldilocks pattern. If stratification is very strong, gases build up but remain trapped. If there is little to no stratification, frequent mixing and higher oxygen levels may reduce methane production. Somewhere in between—where light penetrates, plants grow, and stratification is moderate—methane emissions may peak.

Mud Pond appears to fall into this middle zone, explaining its exceptionally high methane bubbling rates.

Why This Matters for Climate Change

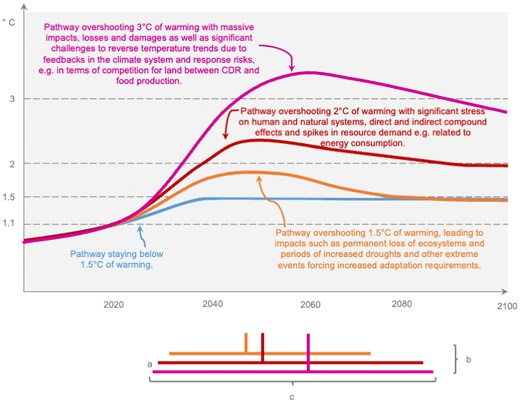

Methane is a particularly powerful greenhouse gas, with a warming potential far greater than carbon dioxide over short timescales. Understanding where and why methane is released is crucial for accurate climate predictions.

Climate change is expected to increase water temperatures, which can strengthen stratification in ponds and lakes. This could alter methane emissions in complex and unpredictable ways. Without understanding these mechanisms, scientists risk underestimating the role of small water bodies in global warming.

What Comes Next

Holgerson’s team is continuing to study these ponds to better understand how disturbances affect emissions. In 2024, they deliberately mixed the waters of Texas Hollow Pond using a generator and circulator, simulating the effects of a summer storm. This experiment aimed to measure how sudden mixing events influence greenhouse gas release.

The researchers are also expanding their work to include 16 additional ponds across New York State. By studying a broader range of pond types, they hope to determine whether the patterns seen in Mud Pond and Texas Hollow Pond are widespread or unique.

Extra Context: Why Freshwater Research Is Evolving

Freshwater ecosystems are gaining attention in climate science because they respond quickly to environmental change. Unlike oceans, ponds and lakes can shift their behavior within seasons or even days. This makes them valuable indicators of how warming temperatures and changing weather patterns influence carbon cycling.

Historically, global climate models have focused on forests, soils, and oceans. Studies like this one show that small freshwater systems deserve a seat at the table.

As scientists continue refining carbon budgets, research on ponds will help close important gaps in our understanding of greenhouse gas emissions. What may look like a quiet pond in the woods could, in reality, be a powerful contributor to atmospheric change.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.70273