Tracking PFAS Through the Food Web Reveals Why Not All “Forever Chemicals” Behave the Same

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, better known as PFAS, are often described as “forever chemicals” because they resist breaking down in the environment. They show up in water, soil, wildlife, food, and even human blood. Because they are so widespread, scientists already expect to find them almost everywhere they look. What researchers at the University at Buffalo did not expect, however, was to see how dramatically the structure of one specific PFAS changes as it moves through the food web.

Their work shows that not all PFAS isomers behave the same, and that difference could matter far more than current regulations acknowledge.

PFOS and Why Its Isomers Matter

The chemical at the center of this research is perfluorooctanesulfonic acid, commonly known as PFOS. PFOS was once widely used in products such as nonstick cookware, stain-resistant fabrics, and firefighting foams. Although its use has been restricted or phased out in many countries, PFOS persists in the environment and continues to circulate through ecosystems.

PFOS does not exist as a single uniform molecule. Instead, it appears in several isomers, which are molecules that share the same chemical formula but differ in how their atoms are arranged. In the case of PFOS, these arrangements fall into two broad categories: branched isomers and linear isomers.

These structural differences may sound minor, but they strongly influence how PFOS behaves. Branched isomers tend to be compact and spherical, making them more soluble in water. Linear isomers are more elongated, which allows them to bind more easily to proteins and persist longer in living tissue.

Despite these differences, current U.S. and European regulations generally group all PFOS isomers together, treating them as though they pose the same environmental and health risks.

Following PFOS Across the Food Web

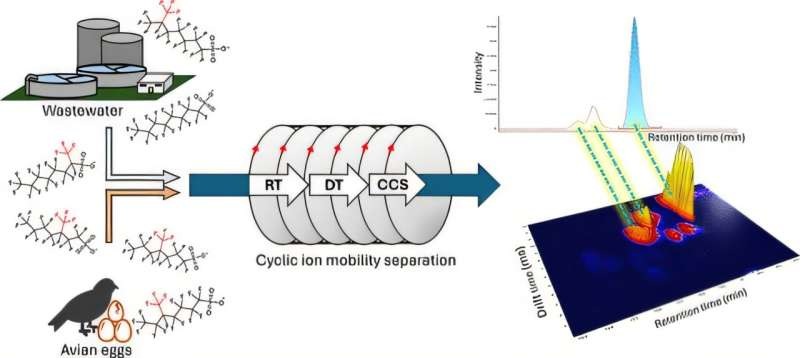

To better understand how PFOS isomers move through the environment, University at Buffalo chemists analyzed samples from water, fish, and bird eggs. The work spanned two related studies, published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry and the Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry.

In wastewater samples and supermarket fish, the researchers found that branched PFOS isomers made up more than half of the total PFOS detected. This result aligns with what scientists expect, since branched isomers dissolve more easily in water and remain mobile in aquatic environments.

The surprise came when the team examined egg yolks from fish-eating birds, specifically double-crested cormorants nesting near Buffalo Harbor. In these eggs, nearly 90% of the PFOS was in the linear form.

This dramatic shift suggests that as PFOS moves from water into fish and then into birds, linear isomers become increasingly dominant, while branched isomers appear to drop out or accumulate less efficiently.

What Fish Can Tell Us About PFAS Exposure

The fish portion of the research focused on seven unfrozen supermarket fish samples, representing both benthic and pelagic species. Benthic fish live and feed near the bottom of rivers, lakes, or oceans, while pelagic fish inhabit open water.

The benthic species included blue catfish, cod, and haddock, while the pelagic group included rainbow trout, salmon, and tilapia.

Using advanced analytical tools, the researchers discovered that benthic fish contained more types of branched PFOS isomers than pelagic fish. In fact, two specific branched PFOS isomers were detected only in benthic species and not in pelagic ones.

Because benthic fish carried both branched and linear isomers, their total PFOS concentrations were significantly higher than those found in pelagic fish. These bottom-dwelling species also tended to contain longer-chain PFAS, such as PFOA (eight carbons) and PFNA (nine carbons), which are known for their persistence and potential toxicity.

This finding raises concerns for consumers, as it suggests that people who frequently eat bottom-dwelling fish may face higher overall PFAS exposure.

Wastewater vs. Bird Eggs: A Clear Isomer Flip

The second study compared PFOS isomers in municipal wastewater and bird egg yolks. The wastewater samples were collected from a treatment facility in Erie County, while the eggs came from abandoned cormorant nests near Buffalo Harbor.

In wastewater, branched PFOS isomers dominated, accounting for more than half of the total PFOS present. In contrast, the bird eggs showed the opposite pattern, with linear PFOS isomers making up nearly 90%.

Scientists already know that linear isomers tend to accumulate more strongly in tissue than branched ones. However, the extreme skew toward linear PFOS in bird eggs suggests that biological processes may selectively retain or transfer linear forms as PFOS moves up the food chain.

The exact mechanisms behind this shift are still unclear and will require further study. What is clear is that PFOS does not move through ecosystems in a uniform way.

How Scientists Can Even See These Differences

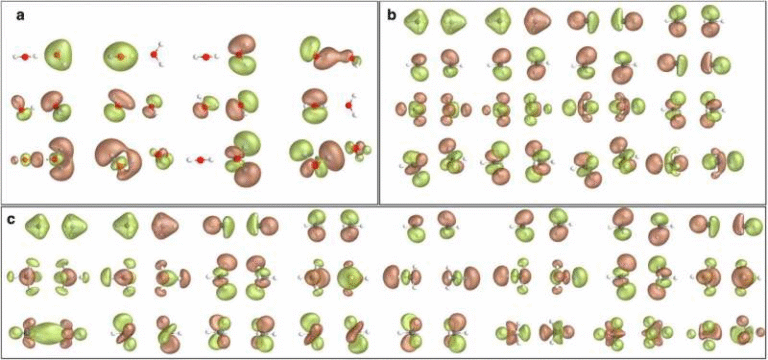

Distinguishing PFOS isomers is not easy. Traditional chemical analyses often cannot separate molecules that share the same mass and formula. To overcome this challenge, the University at Buffalo team used cyclic ion mobility spectrometry, an advanced technique that separates molecules based on shape, not just weight.

In this method, ions travel through a tube filled with an inert gas, such as nitrogen. Compact, spherical molecules move faster, while elongated ones drift more slowly. This difference in drift time allows scientists to distinguish branched PFOS isomers from linear ones with high precision.

Without this technology, the isomer-specific patterns observed in fish, wastewater, and bird eggs would have remained hidden.

Why This Matters for Regulation and Public Health

One of the most important implications of this research is its challenge to current regulatory approaches. By treating all PFOS isomers as a single group, regulations may overlook meaningful differences in bioaccumulation, persistence, and potentially toxicity.

If linear isomers are shown to accumulate more readily in tissues and persist longer in food webs, they may pose a greater long-term risk than branched forms. Understanding these distinctions could eventually support isomer-specific monitoring and regulation, rather than broad chemical categories.

The findings also raise the possibility that chemical design could evolve. If branched structures are shown to bioaccumulate less, future materials could potentially be engineered to favor less persistent molecular shapes.

A Broader Look at PFAS in the Environment

PFAS include thousands of related compounds, many of which are still poorly understood. They are valued for their resistance to heat, water, and oil, but those same properties make them difficult to remove once released into the environment.

Studies increasingly show that PFAS exposure is linked to immune system effects, developmental issues, and certain cancers. As analytical techniques improve, scientists are discovering that structure matters, sometimes in ways that dramatically change how these chemicals interact with living systems.

This research adds another important piece to the puzzle by showing that chemical identity alone is not enough. Molecular shape can determine how a pollutant moves, where it accumulates, and how long it stays.

Research References

PFAS Isomers Matter: Distribution Patterns of Linear and Branched PFOS and PFOA in Consumed Fish Revealed by Cyclic Ion Mobility Separation

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.5c08608

Isomer-Specific Analysis of PFOS in Wastewater and Avian Eggs Enabled by Cyclic Ion Mobility Spectrometry

https://doi.org/10.1021/jasms.5c00219