Common Antibiotics Can Quietly Trigger Immune Responses Through Gut Microbiome Metabolites

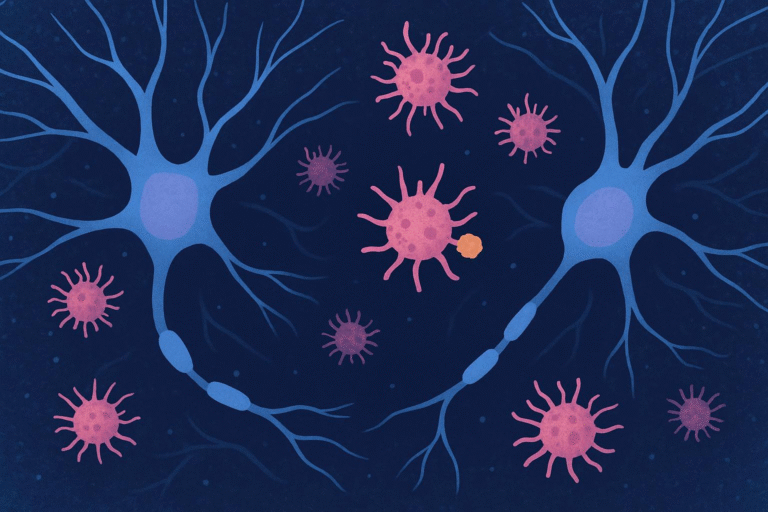

Scientists have long known that the trillions of microbes living in our gut play a major role in digestion, metabolism, and overall health. What is becoming increasingly clear is that these microbes do far more than just help process food. They actively respond to medications we take, sometimes in surprising ways. A new study published in ACS Central Science reveals that commonly prescribed tetracycline antibiotics can prompt gut bacteria to release previously unknown chemical signals that interact directly with the human immune system.

This research adds a new layer to our understanding of how antibiotics affect the body, going well beyond their well-known role in killing or suppressing harmful bacteria.

How Drugs Interact With Gut Microbes

Every day, millions of people take prescription drugs for infections, allergies, high blood pressure, cancer, and many other conditions. While these drugs are designed to act on human cells or invading pathogens, they inevitably come into contact with the gut microbiome, a dense ecosystem of bacteria, fungi, and other microbes living primarily in the large intestine.

Antibiotics are especially impactful because they are meant to target bacteria. However, they often do not distinguish between harmful pathogens and beneficial gut microbes. For years, scientists have suspected that drugs might do more than just kill microbes — they might also change microbial metabolism, altering the compounds bacteria produce and release inside the body.

The new study puts strong evidence behind that idea.

Focusing on a Key Gut Bacterium

The research team, led by chemist Mohammad Seyedsayamdost, focused on one of the most abundant bacterial groups in the human gut: Bacteroides. These bacteria can make up as much as a quarter of the gut microbiome in healthy adults. In particular, the researchers studied Bacteroides dorei, a species already known for its role in immune interactions.

The team had previously shown that exposure to external molecules could awaken “silent” metabolic pathways in marine and soil microbes, causing them to produce compounds that are normally hidden. In this new work, they applied that same concept to human gut bacteria, asking a simple but powerful question: how do gut microbes respond when exposed to FDA-approved drugs?

Testing Hundreds of Prescription Drugs

To find answers, the researchers exposed cultures of Bacteroides dorei to hundreds of FDA-approved medications, including antihistamines, blood pressure drugs, anticancer agents, and antibiotics. They then compared the chemical output of treated bacterial cultures with untreated ones.

Using advanced analytical techniques, the team isolated and identified compounds secreted by the bacteria under each condition. While many drugs caused minor or negligible changes, one class stood out dramatically: tetracycline antibiotics.

Even at low doses, tetracyclines triggered a strong metabolic response in B. dorei, leading the bacteria to produce compounds that had never been characterized before.

Discovery of New Microbial Compounds

The researchers identified two main types of molecules induced by tetracycline exposure:

- Doreamides, a newly named group of compounds discovered in this study

- N-acyladenosines, a class of molecules linked to immune signaling

These compounds were not present, or appeared only at very low levels, in untreated bacterial cultures. Their production increased significantly when B. dorei was exposed to tetracycline antibiotics, suggesting that the drugs acted as metabolic triggers rather than simply as bacterial suppressors.

This finding is important because it shows that antibiotics can actively shape what gut bacteria produce, not just whether they survive.

Effects on the Human Immune System

Finding new bacterial compounds was only part of the story. The researchers then tested what these molecules actually do inside the body.

When human immune cells were exposed to the doreamides and N-acyladenosines, the cells began producing pro-inflammatory cytokines. Cytokines are signaling proteins that help coordinate immune responses, especially during infections. The induced cytokines are known to play roles in activating immune defenses and mobilizing other immune cells.

Even more interesting, the doreamides also stimulated immune cells to produce antimicrobial peptides. These peptides can inhibit the growth of several bacterial strains, including known pathogens. Crucially, they did not inhibit the growth of Bacteroides dorei itself.

This suggests a sophisticated interaction where the bacterium indirectly helps shape its surrounding microbial environment by nudging the host immune system to suppress competing or harmful microbes.

A Secondary Effect of Antibiotic Treatment

Traditionally, antibiotics are thought to influence health primarily by killing bacteria directly. This study shows there is another layer at work.

Low-dose tetracyclines did not simply damage gut microbes. Instead, they caused B. dorei to release immune-active metabolites that can:

- Stimulate immune responses

- Encourage production of antimicrobial peptides

- Potentially reshape the balance of microbes in the gut

This means antibiotics may have indirect effects on immunity and microbial communities through chemical signaling, even when they are not wiping out large numbers of bacteria.

Why This Matters for Human Health

The findings raise intriguing questions about how long-term or low-dose antibiotic use might influence inflammation, immunity, and gut balance. Tetracyclines are commonly prescribed not only for infections but also for conditions like acne and inflammatory diseases, sometimes over extended periods.

If antibiotics consistently trigger immune-modulating compounds from gut bacteria, they could contribute to subtle immune changes over time. These effects might be beneficial in some contexts, such as boosting defense against pathogens, but could also have unintended consequences if immune activation becomes excessive.

Understanding the Gut Microbiome’s Chemical Language

This study highlights how much remains unknown about the chemical dialogue between gut microbes and their human hosts. Many bacterial genes involved in producing bioactive compounds remain silent under standard laboratory conditions. Only when microbes encounter specific triggers — like certain drugs — do these hidden pathways turn on.

This helps explain why the gut microbiome continues to surprise researchers. It is not a static ecosystem, but a dynamic one that responds actively to diet, environment, and medications.

What Comes Next

The researchers emphasize that these findings are an early step. The next phase involves animal studies to determine how these antibiotic-induced metabolites behave in living organisms. Scientists want to know how they influence immunity, inflammation, and microbial balance over time.

There is also interest in whether compounds like the doreamides could have therapeutic potential, either by enhancing antimicrobial defenses or by modulating immune responses in a controlled way.

The Bigger Picture of Drug–Microbe Interactions

This work fits into a growing field known as pharmacomicrobiomics, which studies how drugs and microbes influence each other. As researchers continue to explore this space, it is becoming clear that medications do not act in isolation. They interact with the vast microbial communities inside us, often in unexpected ways.

Understanding these interactions could one day help doctors choose treatments that work more effectively while minimizing unintended side effects on the microbiome and immune system.

Research Paper:

https://doi.org/10.1021/acscentsci.5c00969