Climate Migration Is More Than Staying or Leaving and Researchers Call This Middle Path Tethered Resilience

Climate change is forcing communities across the world to confront difficult questions about their future. Rising temperatures, stronger storms, recurring floods, coastal erosion, and degrading farmland are reshaping everyday life for millions of people. When faced with these pressures, the conversation often becomes simplified into two choices: stay and adapt or leave and migrate. New research argues that this framing misses a large and important part of reality.

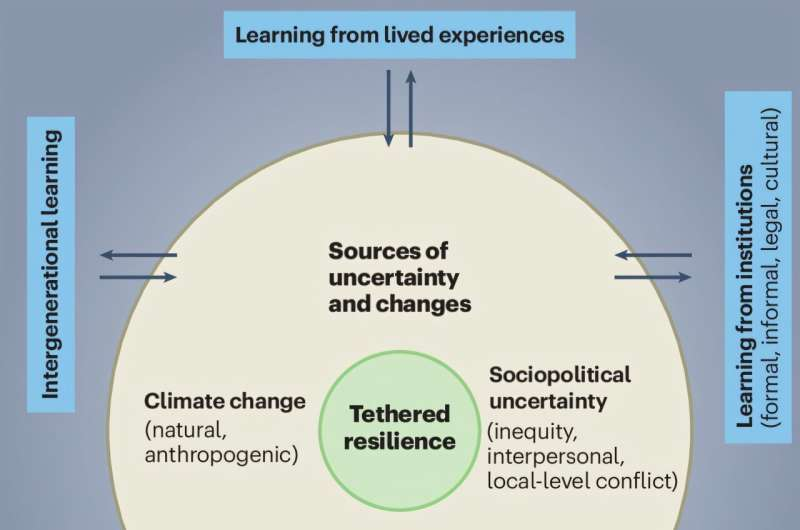

A recent commentary published in Nature Climate Change introduces a third way of understanding how people respond to climate risk. Researchers call this approach tethered resilience, a framework that highlights how people often combine mobility and rootedness rather than choosing one over the other. The study was co-authored by Brianna Castro, an assistant professor of urban sustainability at Yale University, along with an international team of scientists led by human geographer Bishawjit Mallick from the University of Utrecht.

The key message is simple but powerful: many people living in climate-vulnerable areas are not trapped, passive, or failing to adapt. Instead, they are making active, forward-looking decisions shaped by social ties, cultural identity, economic realities, and long-term planning.

Moving Beyond the Stay-or-Go Binary

For years, climate migration has been discussed in binary terms. People were either expected to move away from danger or remain in place and adapt. This perspective often treats migration as the ultimate solution and staying as a sign of vulnerability or lack of options.

The researchers argue that this framing is misleading. In reality, many individuals and families do not see their choices as either permanent relocation or total immobility. Instead, they engage in temporary, seasonal, or generational mobility while maintaining strong connections to their home regions.

This mix of movement and attachment is what the researchers define as tethered resilience. Climate risks matter, but they are often secondary to other factors such as employment opportunities, family responsibilities, cultural heritage, and access to land.

What Exactly Is Tethered Resilience?

Tethered resilience describes a situation where people remain deeply connected to place while still using mobility as a tool to manage risk and plan for the future. Being tethered does not mean being stuck. It means staying connected through identity, family, culture, and livelihood, even if movement becomes part of survival.

The framework emphasizes that people draw on:

- Intergenerational ties, including inherited land and family responsibilities

- Social networks, such as extended families and community groups

- Cultural identity, traditions, and spiritual connections to land

- Economic strategies, including remittances, local enterprises, and seasonal work

In this view, migration is not necessarily a last resort or failure. It can be a strategic choice that exists alongside staying rooted.

Real-World Examples From Around the Globe

The paper grounds its argument in several concrete case studies that show how tethered resilience plays out in different contexts.

In Fiji, families living in climate-vulnerable coastal areas are choosing to stay for now. At the same time, they are planning a generational retreat. Parents remain in place while preparing for their children to eventually move inland and build homes on higher ground. This approach allows families to protect cultural ties to ancestral land while still preparing for future climate impacts.

In Guatemala, climate change has intensified drought and crop failure, especially in rural regions. Younger residents are responding not by leaving immediately, but by supporting local economic initiatives that improve livelihoods. These efforts are seen as a way to strengthen the community so people can continue living there despite environmental stress.

In rural Bangladesh, traditional gender roles often limit women’s mobility. Rather than framing this as immobility or entrapment, the researchers highlight how women are engaging in resilience-building activities such as community farming and home-based enterprises. These strategies help households adapt while maintaining strong local ties.

Across these cases, staying in place is not about denial or lack of awareness. It is about balancing risk, opportunity, and identity.

Four Key Factors Shaping Climate Decisions

The researchers identify four major influences that shape how people respond to climate risk, regardless of whether they move, stay, or do both.

First is the presence of opportunities to blend ancestral practices with innovation. Communities are more likely to adapt successfully when traditional knowledge can be combined with new technologies or methods.

Second are cultural values that prioritize heritage, identity, and continuity. For many people, land is not just an economic asset but a source of meaning and belonging.

Third is the level of government and institutional support. Infrastructure, land rights, access to credit, and adaptation funding all influence whether people can safely remain connected to place.

Fourth are structural inequalities, which disproportionately affect marginalized groups. These inequalities shape who has options, who bears the greatest risk, and whose resilience strategies are recognized or ignored.

Together, these factors show that climate decisions are rarely driven by environmental change alone.

Rethinking Climate Migration Narratives

One of the most important contributions of the study is how it challenges common myths around climate migration. The researchers dispute the idea that climate change is already causing massive, uniform waves of displacement. They also reject the assumption that staying put represents failure or ignorance.

Instead, they show that mobility plus rootedness can function as a deliberate and effective adaptation strategy. This reframing encourages policymakers and researchers to move away from one-size-fits-all solutions.

By recognizing tethered resilience, adaptation becomes a dynamic and proactive process, not a static outcome.

Why This Matters for Policy and Planning

Understanding tethered resilience has significant implications for climate policy. If policymakers assume people will simply relocate, they may overlook investments that support adaptation in place.

The researchers argue for greater attention to social infrastructure, including community networks, education, and local institutions. Supporting the right to stay and adapt is just as important as facilitating safe migration pathways.

Flexible, context-specific solutions are more likely to succeed than rigid relocation plans. When people’s attachment to land, identity, and community is respected, adaptation strategies become more realistic and sustainable.

Broader Context on Climate Mobility

Globally, most climate-affected people move short distances, not across borders. Temporary migration, circular migration, and seasonal work are already common coping strategies in many regions. Tethered resilience helps explain these patterns by showing how movement and stability coexist.

This framework also aligns with growing research in human geography and development studies that emphasizes agency, rather than portraying climate-affected populations as helpless victims.

Looking Ahead

As climate risks continue to grow, understanding how people actually respond becomes increasingly important. Tethered resilience offers a more nuanced lens for examining climate adaptation, one that respects complexity rather than forcing simple categories.

By acknowledging that people adapt in mixed and creative ways, this research opens the door to more humane and effective responses to climate change.

Research paper:

Future-making beyond (im)mobility through tethered resilience, Nature Climate Change (2025)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-025-02506-8