Deep-Sea Microbes Reveal a Stunning Protein Engineering Secret Hidden at Ocean Vents

Scientists have uncovered an elegant piece of natural engineering hidden thousands of meters below the ocean’s surface, inside one of the most extreme environments on Earth. A deep-sea microbe known as Pyrodictium abyssi—a heat-loving archaeon that thrives near hydrothermal vents—uses microscopic protein tubes to physically link cells together into a remarkably stable community. Until recently, no one fully understood how these delicate-looking structures could survive such punishing conditions. Now, a new study has revealed exactly how they are built, why they are so strong, and why they matter far beyond microbiology.

Life in One of Earth’s Harshest Environments

Pyrodictium abyssi is not your average microbe. It belongs to Archaea, the so-called third domain of life, separate from bacteria and eukaryotes. This organism lives in deep-sea hydrothermal vents, environments characterized by temperatures above the boiling point of water, crushing pressure, total darkness, and a complete absence of oxygen.

Despite these conditions, Pyrodictium abyssi not only survives but forms tightly connected communities. Its cells are linked by a dense network of hair-thin protein tubes called cannulae, creating a kind of biological mesh that holds the population together. These tubes are not optional features—this species always forms them, suggesting they offer a major evolutionary advantage.

The Mystery of Cannulae

Cannulae have fascinated scientists since Pyrodictium abyssi was first isolated in 1991 by German microbiologist Karl Stetter. These structures extend from the surface of one cell to another, forming a physical network that can span entire microbial colonies. However, for decades, researchers did not understand how these tubes formed or how they remained intact under such extreme conditions.

The new study, published in Nature Communications, finally answers those questions. The research was led by scientists from Emory University, the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, and Vrije Universiteit Brussel in Belgium, with contributions from institutions in Canada and Germany.

Seeing the Invisible With Cryo-EM

A major breakthrough came from advances in cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), a technique that allows scientists to visualize biological structures at near-atomic resolution. Over the past decade, cryo-EM has undergone what researchers call a “resolution revolution,” making it possible to see individual protein molecules in unprecedented detail.

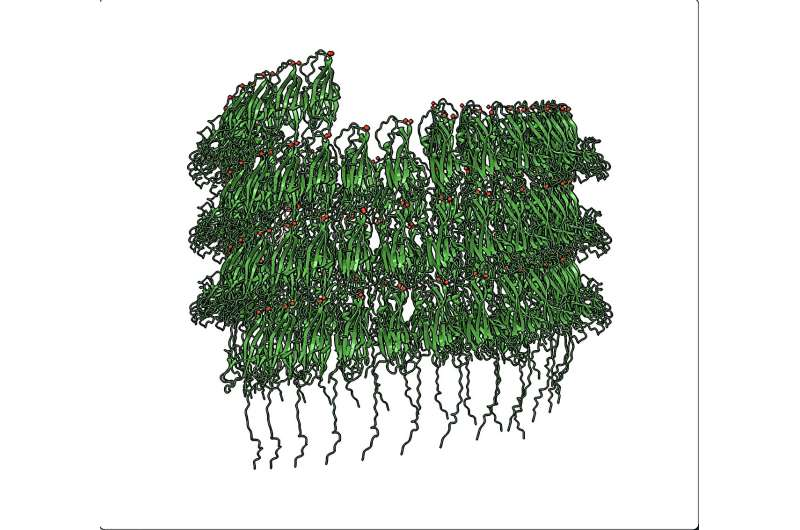

Using cryo-EM, the research team captured high-resolution 3D images of cannulae extracted directly from Pyrodictium abyssi. These images revealed that cannulae are composed of repeating protein units arranged with striking precision, forming long, hollow tubes with fluted edges reminiscent of classical architectural columns.

A Surprisingly Simple Assembly Process

One of the most striking discoveries is how simple the cannulae assembly process is. Unlike many cellular structures that require complex machinery to build, these protein tubes assemble without any chaperones, motors, or cellular scaffolding.

The key trigger is calcium. When calcium ions are present, individual protein molecules begin linking together through a process known as donor strand complementation. In simple terms, part of one protein inserts itself into a neighboring protein, locking them together. This process repeats over and over, forming a growing tube.

Each new protein added to the structure helps stabilize the next one, creating a domino effect. Calcium ions remain embedded within the structure, acting like molecular mortar that strengthens the entire assembly. The result is a tube that is both beautifully ordered and extraordinarily strong.

Why Cannulae Are So Tough

Cannulae must endure extreme heat, pressure, and chemical stress. The study showed that their strength comes from several factors working together:

- Tightly interlocked protein strands that resist separation

- Calcium coordination that reinforces connections between proteins

- A structure dominated by beta-sheet folds, which are known for their stability

Together, these features allow cannulae to remain intact in conditions that would destroy most biological materials.

How Scientists Studied Cannulae Without the Microbe

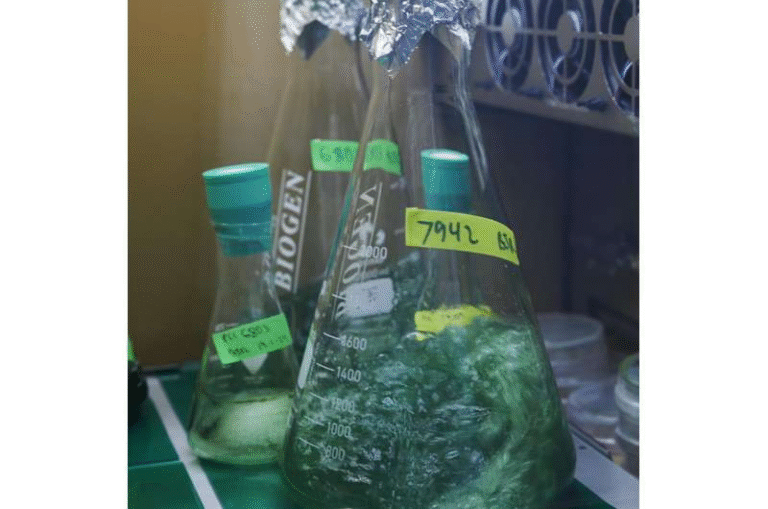

Working directly with Pyrodictium abyssi is extremely challenging. The microbe requires high pressure, hydrogen gas, and oxygen-free conditions to survive. It also produces hydrogen sulfide, a gas that is both toxic and highly corrosive.

To overcome this, researchers took a clever approach. They synthesized the gene that encodes the cannulae protein and inserted it into laboratory strains of E. coli. These bacteria then produced the protein in large quantities, allowing scientists to study cannulae safely and efficiently.

Importantly, when the lab-grown cannulae were compared to those taken from real Pyrodictium abyssi cells, they were found to be structurally identical. This confirmed that the synthetic system accurately replicates the natural one.

A Possible Cellular Transport Network

Beyond their structural role, cannulae may serve as transport highways between cells. High-resolution images revealed helix-shaped material inside some cannulae, hinting that they may carry cargo.

One strong candidate is DNA. The interior of cannulae is positively charged, which would naturally attract negatively charged DNA molecules. While the study did not find enough material to conclusively identify DNA, the evidence suggests that cannulae may enable genetic exchange or communication across the microbial network.

Early Clues About Multicellular Life

The discovery also has evolutionary implications. Pyrodictium abyssi may represent a primitive step toward multicellularity, showing how single-celled organisms can cooperate physically and possibly exchange information. This kind of connectivity could have played a role in the emergence of more complex life forms on early Earth.

Why This Matters for Biotechnology

Cannulae are attracting attention far beyond microbiology. Their combination of strength, simplicity, and self-assembly makes them highly appealing for technological applications. Researchers are exploring their use as:

- Protein-based biomaterials

- Nanoscale delivery systems for drugs

- Encapsulation tubes for charged particles

The team has already demonstrated that cannulae can encase negatively charged gold nanoparticles, which are widely used in biomedical imaging and targeted drug delivery. This opens the door to designing customizable protein tubes for medical and industrial use.

Open Science and Global Collaboration

The researchers deposited the cannulae structure into the Protein Data Bank, an open-access repository used by scientists worldwide. This allowed other teams, including those working with real Pyrodictium abyssi specimens in Belgium, to compare results and confirm the findings.

This open sharing of data helped turn individual efforts into a truly international collaboration, accelerating progress and validation.

A Remarkable Example of Nature’s Engineering

What makes this discovery especially compelling is not just the strength of cannulae, but their elegant simplicity. With just protein building blocks and calcium ions, Pyrodictium abyssi constructs durable structures capable of surviving some of the harshest conditions known.

It is a powerful reminder that nature often solves complex engineering problems with surprisingly minimal tools—and that even the smallest organisms can teach us big lessons about design, resilience, and innovation.

Research paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-64120-8