High Seas Fisheries Management Is Falling Short and a New Global Study Explains Why

Managing the world’s oceans is no small task, especially when it comes to the vast areas that lie beyond national borders. A new scientific analysis has taken a hard look at how global fisheries are being managed on the high seas, and the findings raise serious concerns about the future of marine ecosystems, food security, and international ocean governance.

The study, led by researchers from Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment, concludes that the organizations responsible for regulating fishing across most of the open ocean are not meeting their conservation and sustainability mandates. This comes at a crucial moment, as the United Nations prepares to enforce a landmark treaty aimed at protecting biodiversity in international waters.

What Are the High Seas and Why Do They Matter?

The high seas refer to ocean areas that lie more than 200 nautical miles from national coastlines. These waters make up nearly 65% of the world’s oceans, placing them outside the direct jurisdiction of any single country. Despite their remoteness, they are far from empty.

These regions are home to migratory and ecologically critical species, including tuna, sharks, whales, sea turtles, and many deep-sea fish. Many of these species move across entire ocean basins or migrate between national waters and the high seas, making coordinated international management essential.

The high seas also play a key role in global food systems and economies, particularly through industrial fishing. However, this same industrial activity is also the main driver of biodiversity decline in these waters.

The Role of Regional Fisheries Management Organizations

To manage fishing on the high seas, countries rely on Regional Fisheries Management Organizations, commonly known as RFMOs. These bodies are made up of member nations and are responsible for regulating fishing activities, setting catch limits, and protecting fish stocks within specific ocean regions or for specific species.

Each RFMO typically has:

- A scientific committee that assesses fish stock health

- Decision-making bodies that set binding rules

- A dual mandate to ensure long-term conservation and sustainable use

Despite this structure, concerns about RFMO effectiveness are not new. An independent review published in 2010 famously concluded that RFMOs were “failing the high seas.”

How This New Analysis Was Conducted

The new study builds directly on that earlier review but expands its scope and depth. The research team evaluated 16 different RFMOs using 10 broad management categories, including:

- Sustainable catch targets

- Bycatch management

- Monitoring and enforcement

- Transparency and data availability

- Stakeholder and Indigenous representation

Within these categories, the researchers assessed 100 individual criteria, each worth one point, with partial credit allowed. All evaluations were based on publicly available information, making the assessment transparent and replicable.

The highest possible score was 100.

The Results Are Hard to Ignore

The findings paint a troubling picture. Across all organizations:

- Scores ranged from 29.5 to 61.5

- The average score was just 46, less than half of the total possible points

- No RFMO came close to fully meeting its mandate

Perhaps even more alarming is what the study found about fish populations themselves. On average, 56% of fish stocks targeted within RFMO jurisdictions were classified as overexploited or had declined so severely that they could not naturally rebuild.

In other words, more than half of the managed fish populations are already in serious trouble.

Why Performance Is Lagging Behind

According to the researchers, the problem is not simply a lack of scientific knowledge. Most RFMOs have access to solid science and expert advice. The bigger issue lies in slow decision-making, weak enforcement, and gaps between policy and practice.

Several systemic challenges stand out:

- Delayed responses to scientific warnings about declining stocks

- Insufficient action on bycatch, where non-target species are unintentionally caught

- Limited inclusion of Indigenous and non-governmental stakeholders

- Continued allowance of harmful fishing practices

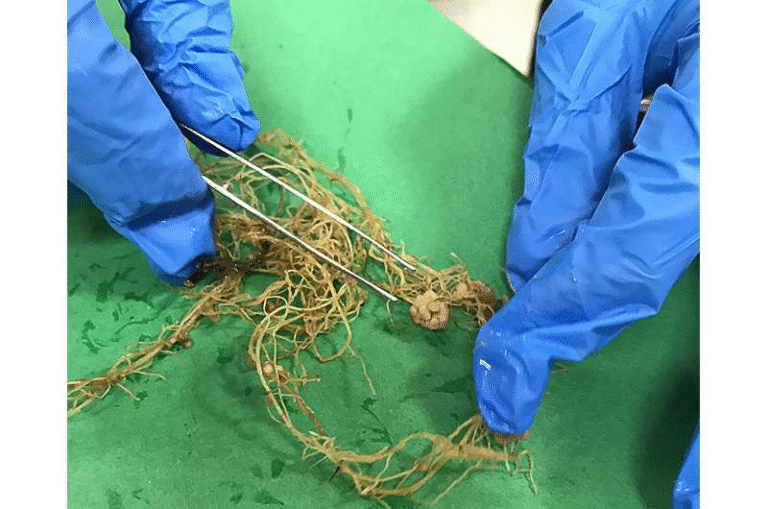

One particularly controversial practice highlighted in the study is transshipment. This involves transferring fish from one vessel to another at sea, often far from oversight. Critics argue that transshipment can enable illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing by allowing illegally caught fish to enter global supply chains unnoticed.

Banning or strictly regulating this practice is identified as one potential step toward better conservation outcomes.

Climate Change Adds More Pressure

While overfishing remains the primary driver of biodiversity loss on the high seas, the study also acknowledges that climate change is becoming an increasingly significant factor.

Warming waters, shifting currents, and ocean acidification are altering fish distributions and migration patterns. Many RFMOs have been slow to incorporate climate considerations into their management frameworks, even though these changes directly affect stock sustainability.

Some progress is being discussed. For example, the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission, which oversees more than half of the world’s tuna catch and includes 26 member nations, recently held discussions on integrating climate change into fisheries management.

Timing Matters: A New UN Treaty Is Coming

The release of this analysis is especially significant given the upcoming enforcement of the United Nations High Seas Treaty, formally known as the agreement on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction.

The treaty is designed to:

- Ensure the conservation and sustainable use of high-seas biodiversity

- Enable the creation of marine protected areas in international waters

- Require legal collaboration with RFMOs

The treaty will come fully into effect on January 17, 2026, and its success will depend heavily on how well RFMOs adapt and cooperate.

The researchers suggest that this treaty could be an opportunity to fill long-standing governance gaps, align conservation goals more closely with science, and prioritize long-term ecosystem health over short-term economic gains.

Why This Matters Beyond the Ocean

High-seas fisheries management is not just an environmental issue. It affects:

- Global food security, particularly for countries dependent on fish protein

- Economic stability for fishing communities

- The health of ocean ecosystems that regulate climate and support biodiversity

When management fails in international waters, the consequences ripple outward, impacting coastal ecosystems and national fisheries as well.

Looking Ahead

Rather than presenting the study as a simple ranking or scorecard, the authors emphasize that their goal is to identify specific areas for improvement. Better monitoring, stronger enforcement, greater transparency, and meaningful inclusion of diverse stakeholders could significantly improve outcomes.

As international attention increasingly turns toward protecting the high seas, this analysis serves as both a warning and a roadmap. The tools to manage these waters more sustainably already exist. The challenge now is finding the political will to use them.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ae1b1e