Mammary Glands in Humans and Livestock May Be Unexpected Gateways for Avian Flu

Researchers studying the ongoing global outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) have uncovered a finding that adds a new and important layer to how this virus may spread between animals and potentially to humans. A new scientific study shows that mammary glands in several livestock species — and even in humans — contain biological features that can make them suitable hosts for avian influenza viruses.

This discovery does not mean widespread new infections are occurring, but it does highlight previously underappreciated pathways through which avian flu could move across species. The findings are especially relevant as the current H5N1 outbreak continues to affect poultry, dairy cattle, and a growing list of mammals worldwide.

The Scale of the Ongoing Avian Flu Outbreak

Since 2022, the ongoing outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza has had an enormous global impact. More than 184 million domestic poultry have been affected, making it one of the most destructive avian flu events in recent history.

In spring 2024, the virus made a significant and concerning jump into U.S. dairy cattle, spreading to more than 1,000 milking cow herds. This marked the first time H5N1 was seen spreading efficiently among cattle, raising questions about how the virus was adapting to mammalian hosts.

Why Mammary Glands Matter in Influenza Infection

The new study, led by researchers from Iowa State University (ISU) in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Animal Disease Center, focused on a specific biological factor: sialic acids.

Sialic acids are sugar molecules found on the surface of many animal cells. For influenza viruses, they act as docking stations, allowing the virus to attach to a cell and begin infection. Different influenza viruses prefer different forms of sialic acid, which is one reason some flu strains infect birds while others infect humans.

The researchers examined mammary gland tissue from a wide range of species and found high levels of sialic acid receptors that are compatible with avian influenza viruses.

Livestock Species Found to Have Avian Flu Receptors

The study revealed that mammary glands from multiple domesticated animals contain these influenza-friendly receptors. The species examined included:

- Pigs

- Sheep

- Goats

- Beef cattle

- Alpacas

- Dairy cattle

In all of these animals, mammary gland tissue showed the presence of receptors preferred by avian influenza A viruses. This suggests that the mammary glands themselves could support infection if the virus reaches them.

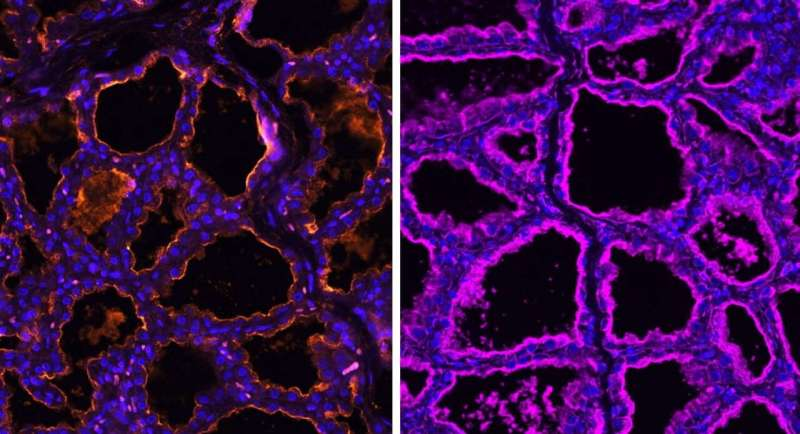

Microscope imaging from the study clearly demonstrated this receptor distribution. In pig mammary tissue, for example, receptors associated with avian influenza appeared alongside receptors typically used by influenza strains that infect mammals.

Human Mammary Tissue Shows Similar Receptors

One of the most striking findings of the study was that human breast tissue also contains the same types of sialic acid receptors. This does not mean human mammary glands are actively spreading avian flu, but it does show that the tissue is biologically capable of binding influenza viruses under the right conditions.

This discovery adds to broader concerns about how influenza viruses adapt as they move between species. The presence of both avian-type and human-type receptors in the same tissue raises questions about viral evolution and reassortment, where different flu strains exchange genetic material.

Lessons from Dairy Cattle and Milk Contamination

The findings build directly on earlier research by many of the same scientists. A previous study showed that dairy cow udders have exceptionally high levels of sialic acid receptors. This helped explain why H5N1 was able to spread so efficiently among dairy herds once it entered cattle populations.

In infected dairy cows, the virus has been detected at high levels in milk. This discovery prompted the U.S. Department of Agriculture to begin nationwide surveillance testing of raw milk samples.

It is important to note that pasteurization kills influenza viruses, making store-bought milk safe to consume. However, the findings raise concerns about the consumption of raw milk, not only from cows but also from other animals such as goats and sheep, whose milk is sometimes consumed unpasteurized.

Milk poses a unique risk because it is transported from farms into communities, potentially allowing the virus to move farther than it could through direct respiratory contact alone.

Why Transmission Risk Is Different with Milk

Respiratory transmission typically requires close contact between infected animals and humans. In contrast, milk can travel long distances and reach many people who have no direct contact with livestock.

If a virus contaminates milk at the source, it creates an entirely different exposure scenario. While no large outbreaks linked to raw milk have been documented so far, researchers emphasize that the potential risk deserves serious attention.

Limited Testing Leaves Gaps in Knowledge

So far, only sporadic cases of H5N1 infection have been reported in the non-dairy livestock species examined in the study. However, these animals are not being widely or routinely tested for avian influenza.

This means infections could be going undetected. Without systematic surveillance, scientists cannot fully assess how often these species may be exposed or infected.

The Bigger Concern: Viral Adaptation

All mammary gland tissues examined in the study contained receptors preferred by both avian influenza and seasonal human influenza viruses. This overlap is what concerns scientists most.

When different influenza viruses infect the same host or tissue, they can potentially mix and evolve, creating new variants with unpredictable characteristics. Historically, H5N1 has had a human fatality rate of around 50%, although the current outbreak has resulted in 71 confirmed human cases and two deaths so far.

Researchers stress that limiting opportunities for the virus to replicate in mammals is crucial to reducing the risk of dangerous adaptations.

Understanding Sialic Acids and Influenza

Sialic acids are not unique to mammary glands. They are found throughout the respiratory, digestive, and reproductive systems of many animals. What makes mammary tissue notable is the density and accessibility of these receptors during lactation.

Lactating tissue is highly active, well-supplied with nutrients, and capable of producing large volumes of fluid — conditions that can be favorable for viral replication if infection occurs.

What This Research Means Going Forward

This study does not suggest immediate danger, but it does highlight important blind spots in how avian influenza surveillance is currently conducted. It reinforces the importance of:

- Monitoring non-poultry livestock

- Continuing raw milk surveillance

- Expanding research into non-respiratory transmission routes

- Preventing unnecessary viral spread to limit evolution

Staying ahead of influenza means understanding not just where infections are happening now, but where they could happen next.

Research Paper Reference

Exploring influenza A virus receptor distribution in the lactating mammary gland of domesticated livestock and in human breast tissue

Journal of Dairy Science (2025)

https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2025-26950