Gene Therapy Takes a Major Leap Forward as Scientists Learn to Guide Jumping DNA to Fix Faulty Genes

For decades, gene therapy has held the promise of correcting diseases at their genetic roots, but one major challenge has always stood in the way: how to safely and precisely insert healthy genes into human DNA. A new breakthrough from researchers at the University of Hawaiʻi is now bringing that vision much closer to reality. By harnessing and guiding so-called jumping DNA, scientists have demonstrated a highly accurate method for delivering therapeutic genes exactly where they are needed, with unprecedented efficiency.

At the center of this research is Dr. Jesse Owens, a Cell and Molecular Biology researcher at the John A. Burns School of Medicine (JABSOM). His work builds on a radical idea first proposed more than half a century ago: that DNA is not always fixed in place, but can move around within the genome. This phenomenon, once considered strange and disruptive, is now being transformed into a powerful medical tool.

Understanding Jumping DNA and Transposons

Jumping DNA refers to genetic elements known as transposons. These are segments of DNA capable of cutting themselves out of one location in the genome and inserting themselves into another. Transposons were first discovered in corn by geneticist Barbara McClintock, a finding so groundbreaking that it eventually earned her a Nobel Prize.

For years, transposons were dismissed as “selfish DNA” because of their ability to move randomly and sometimes disrupt important genes. However, scientists later realized that this very ability could be repurposed. If transposons could be controlled, they might become ideal delivery vehicles for therapeutic genes.

Dr. Owens and his team have spent nearly two decades working toward that goal. Their latest study, published in the journal Nucleic Acids Research, demonstrates a major advance in controlling where transposons land in human cells.

Moving Beyond Random Gene Insertion

Early transposon-based gene therapy approaches suffered from a critical flaw: lack of precision. The DNA would insert itself randomly into the genome, raising the risk of disrupting essential genes or activating cancer-related pathways. This randomness made clinical use unsafe.

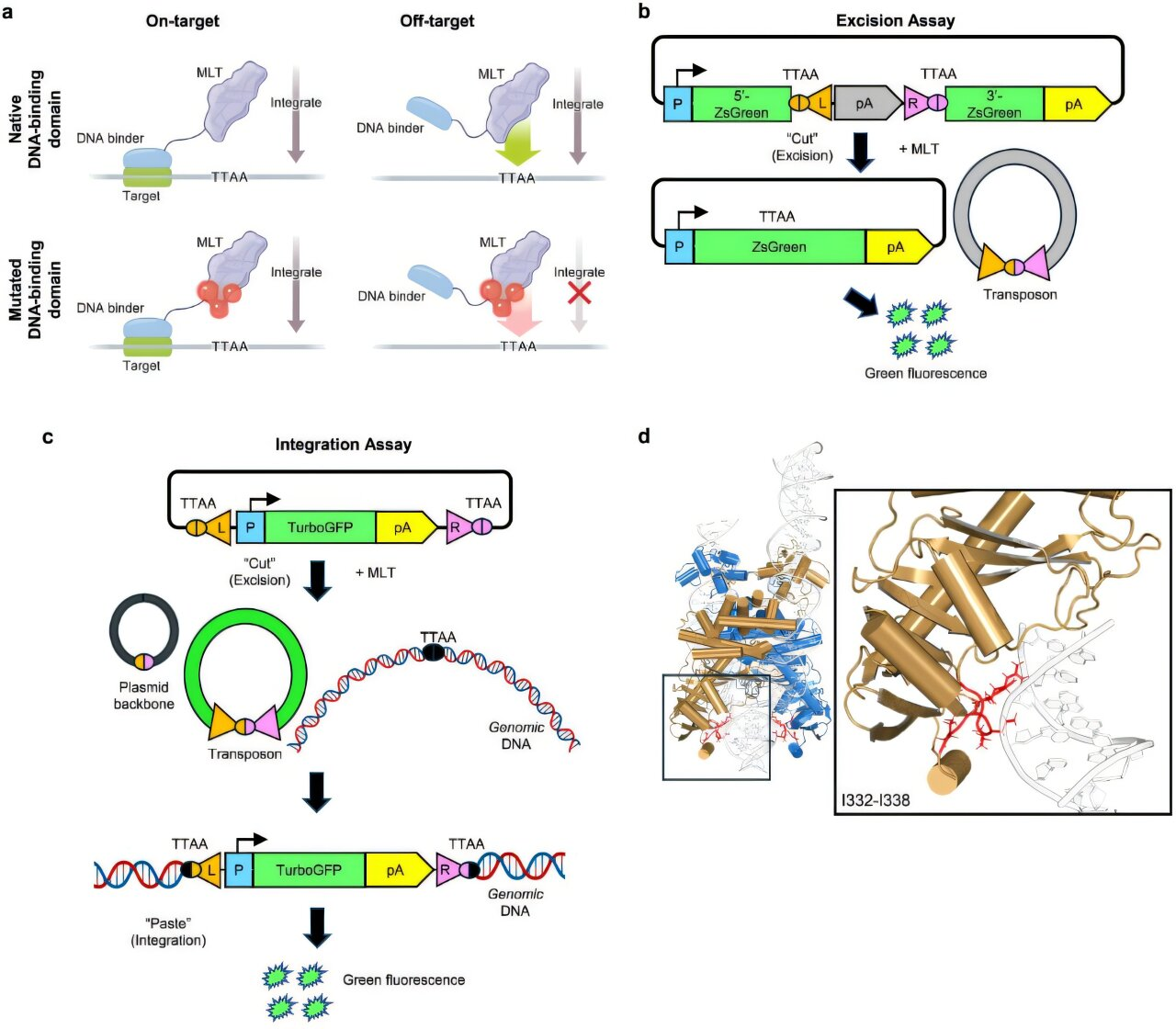

The new research tackles this issue head-on by engineering a site-directed transposase system. A transposase is the enzyme that enables a transposon to move. By modifying specific DNA-binding domains within this enzyme, the research team was able to dramatically reduce off-target insertions and guide the transposon to specific regions of the genome.

These regions, often called genomic safe harbors, are areas of DNA that are open for gene expression but located far away from genes that could trigger cancer or other harmful effects. Targeting these safe harbors is essential for making gene therapy both effective and safe.

Record-Setting Efficiency in Human Cells

One of the most striking results of the study is the level of efficiency achieved. The researchers reported an average of 1.2 successful gene insertions per cell. This is an extraordinary improvement compared to earlier techniques, which often achieved less than 0.1 percent efficiency.

In practical terms, this means that nearly every treated cell successfully received the new gene. Just a few years ago, such results would have been considered unattainable. The improvement represents more than a thousandfold increase over previous generations of transposon-based systems.

Equally important, the team identified specific Exc+Int⁻ DNA-binding domain mutants that minimize unintended integration events. These engineered mutants help ensure that the transposon inserts its genetic cargo only where it is supposed to, keeping off-target activity close to background levels.

Why Avoiding DNA Breaks Matters

Many modern gene-editing techniques, including some CRISPR-based approaches, rely on creating double-strand breaks in DNA. While effective, these breaks can introduce unintended mutations or genomic instability.

The transposon system developed by Owens and his colleagues offers a key advantage: it can insert gene-sized DNA sequences without inducing double-strand breaks. This makes the approach inherently safer and particularly attractive for long-term therapeutic applications.

The system is also capable of inserting relatively large DNA segments, large enough to carry full therapeutic genes rather than partial corrections.

Potential Applications in Genetic Disease

The implications of this work are wide-ranging. One example highlighted by the researchers is hemophilia, a genetic disorder caused by a single defective gene that prevents proper blood clotting. By inserting a corrected version of the gene into a safe harbor region, the body could potentially resume normal protein production, addressing the disease at its source rather than just treating symptoms.

Because the system is highly programmable, it could theoretically be adapted to treat a wide variety of single-gene disorders, many of which currently have limited or no curative treatment options.

A New Tool for Cancer Immunotherapy

Beyond inherited diseases, the research team is also exploring applications in CAR T-cell immunotherapy. This form of cancer treatment involves genetically reprogramming a patient’s own immune cells to recognize and destroy cancer cells.

Precise and efficient gene insertion is critical in CAR T-cell therapy. The new transposon system could allow scientists to insert therapeutic genes into immune cells more reliably and safely than existing methods, potentially improving both effectiveness and accessibility.

How This Fits into the Bigger Picture of Gene Editing

This breakthrough arrives at a time when the field of gene therapy is rapidly evolving. Scientists are exploring multiple strategies to improve precision, safety, and scalability, including CRISPR-associated transposases, prime editing, and other hybrid systems.

What makes this work stand out is its combination of high efficiency, precise targeting, and reduced genomic risk. By avoiding DNA breaks and minimizing off-target effects, the approach addresses several of the most persistent challenges in gene therapy.

Looking Ahead

While the research is still at the laboratory stage, its implications are global. The ability to reliably guide jumping DNA to safe locations in the human genome could reshape how genetic diseases are treated and how cell-based therapies are developed.

Dr. Owens’ work, which began in Hawaiʻi, now sits at the forefront of a field that could impact patients worldwide. Continued development and testing will determine how soon this technology can move toward clinical trials, but the foundation is now firmly in place.

This study marks a clear turning point, showing that jumping DNA is no longer a genetic curiosity, but a powerful and increasingly precise tool for modern medicine.

Research paper reference:

James E. Short et al., “Gene-sized DNA insertion at genomic safe harbors in human cells using a site-directed transposase,” Nucleic Acids Research (2025).

https://academic.oup.com/nar/article/53/22/gkaf1316/8373962