Disabling a Single Stress Gene Helps Protect Pancreatic Cells From Type 1 Diabetes in Mice

Scientists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison have uncovered an intriguing new way to protect the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas from destruction in Type 1 diabetes. Instead of targeting the immune system directly, the researchers focused on the pancreatic beta cells themselves—and the results suggest a completely different way of thinking about how this disease might be prevented or delayed.

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease in which immune cells mistakenly attack and destroy beta cells in the pancreas. These beta cells are responsible for producing insulin, the hormone that regulates blood sugar levels. Once enough of these cells are lost, the body can no longer control glucose effectively, leading to lifelong dependence on insulin therapy. Historically, most research and treatments have tried to calm or suppress the immune system to stop this attack. This new study asks a different question: why are beta cells targeted in the first place?

A closer look at cellular stress inside beta cells

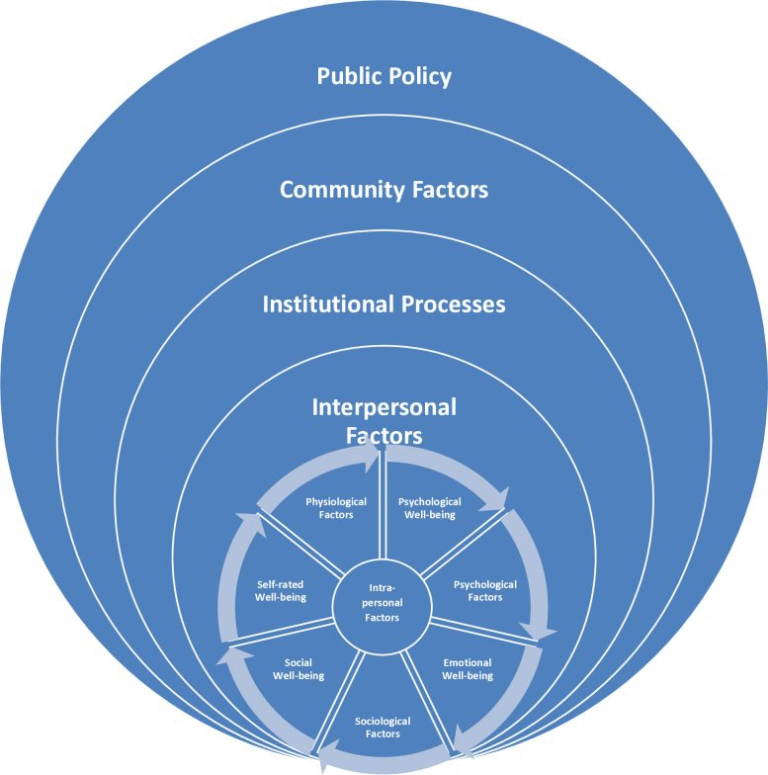

The research centers on a gene called Xbp1, which plays a key role in a cellular system known as the stress response. Cells constantly experience stress from inflammation, environmental toxins, and the buildup of misfolded proteins. To survive, they rely on protective pathways inside a structure called the endoplasmic reticulum, where proteins are folded and processed.

XBP1 is part of the unfolded protein response, a network of signals that helps cells cope when protein production becomes overwhelming. Beta cells are particularly vulnerable to this kind of stress because they produce large amounts of insulin. When stress pathways become overactive, they can change how cells behave—and possibly how the immune system perceives them.

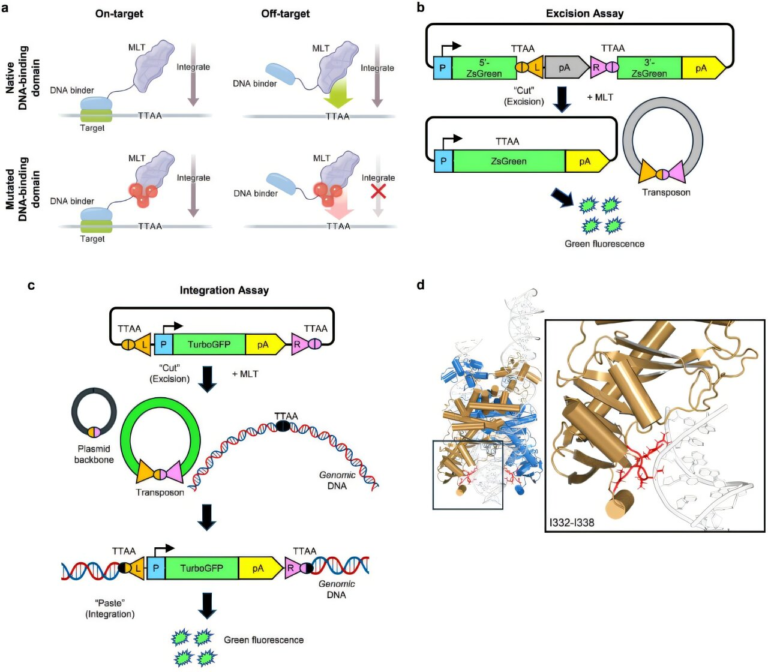

Previous work from the same research group showed that removing another stress sensor, IRE1α, from beta cells could also prevent diabetes in mice. The new study builds on that foundation by examining what happens when Xbp1 is specifically deleted in beta cells.

Testing the idea in diabetes-prone mice

To explore this, the researchers used a well-established mouse model that spontaneously develops Type 1 diabetes, closely mimicking the human disease. In these mice, the immune system naturally begins attacking beta cells as the animals age.

The scientists genetically deleted the Xbp1 gene only in insulin-producing beta cells, and crucially, they did this before the immune attack began. What happened next surprised them.

At first, the mice showed signs of diabetes, including elevated blood glucose levels. However, instead of progressing to full-blown disease, the animals gradually recovered. Their blood sugar levels returned to normal, insulin production stabilized, and the mice remained healthy for up to a year, an unusually long time in this aggressive diabetes model.

Even more striking, the mice were protected without suppressing the immune system, something that has been very difficult to achieve in Type 1 diabetes research.

Why immune cells stop attacking

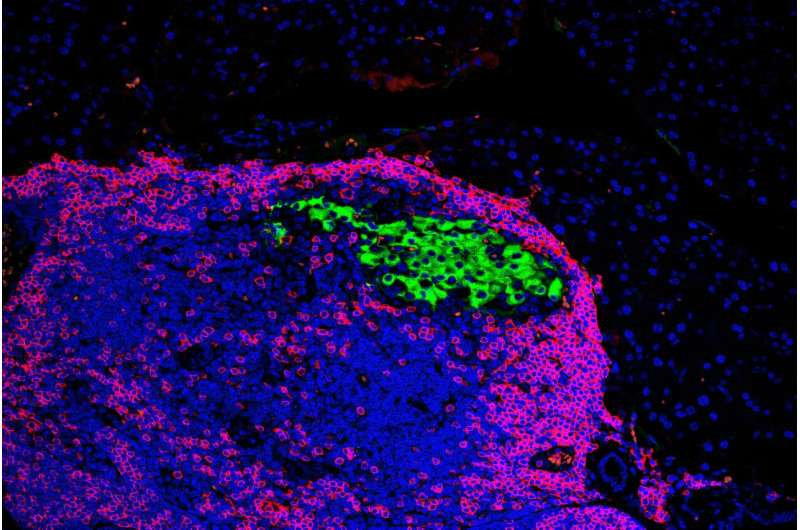

When the team looked more closely at the beta cells lacking Xbp1, they noticed something unusual. These cells temporarily lost their mature beta-cell identity. In simple terms, they stopped looking and behaving like typical insulin-producing cells.

During this phase, the cells expressed fewer of the molecular markers that immune cells use to identify and attack beta cells. As a result, immune cells were less likely to recognize them as targets. This period of reduced visibility appeared to shield the beta cells during the most dangerous phase of immune assault.

Importantly, this change was temporary. Over time, the beta cells regained their mature identity, inflammation in the pancreas decreased, and insulin production recovered. The immune attack did not resume with the same intensity, allowing the cells to survive long-term.

This finding supports a growing idea in diabetes research: beta cells are not just passive victims. Instead, they can actively influence how the immune system responds to them.

Separating the roles of XBP1 and IRE1α

Although XBP1 is normally activated by IRE1α, the study revealed that XBP1 has its own unique functions. The protective effects seen after deleting Xbp1 occurred without altering certain IRE1α-related stress pathways, helping clarify how different components of the stress response contribute to disease.

To make sure the results were reliable, the researchers carefully controlled environmental factors such as housing conditions and diet, which are known to influence diabetes development in mice. They also directly compared mice lacking Xbp1 with mice lacking Ire1α under identical conditions.

Using single-cell sequencing and advanced gene regulatory network analysis, the team identified both shared stress pathways and networks that were specific to Xbp1. Some of these Xbp1-dependent networks had never been described before, highlighting just how complex beta-cell stress biology really is.

A shift in how scientists think about Type 1 diabetes

One of the most important implications of this research is conceptual. For decades, Type 1 diabetes has been viewed almost entirely as a problem of immune dysfunction. This study adds to growing evidence that beta cells themselves play an active role in their own destruction—or survival.

By altering their stress responses and identity, beta cells may influence whether they become immune targets in the first place. That insight opens up new possibilities for intervention that do not rely solely on immune suppression, which often comes with serious side effects.

What this could mean for humans

Although the study was conducted in mice, it was designed with human disease in mind. In people, Type 1 diabetes can often be predicted years before symptoms appear by detecting autoantibodies in the blood. This creates a window of opportunity for early intervention.

The researchers are now asking whether it might be possible to temporarily inhibit XBP1 or related pathways in high-risk individuals to protect beta cells during this early stage. If beta cells could be shielded long enough, it might prevent or delay the onset of diabetes altogether.

To explore this idea, the team is extending its work to lab-grown human pancreatic cells, while continuing animal studies to better understand timing, safety, and long-term effects.

Understanding beta-cell stress beyond diabetes

Beyond Type 1 diabetes, this research also contributes to a broader understanding of cellular stress responses. XBP1 plays roles in immune cells, cancer biology, neurodegenerative diseases, and metabolic disorders. Learning how this gene reshapes cell identity and immune interactions could have implications far beyond diabetes alone.

For now, the findings represent an important step toward rethinking how autoimmune diseases develop—and how they might one day be stopped before irreversible damage occurs.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65635-w