Scientists Discover How the Brain Measures Distance Without Relying on Sight

The human brain has an impressive ability to keep track of where we are, even when visual information is missing. Think about walking through your home at night without turning on the lights—you still manage to judge how far you’ve moved and where you are headed. A new neuroscience study has now shed light on how the brain pulls off this seemingly simple but deeply complex task. Researchers have identified a neural mechanism that acts much like a built-in odometer, allowing the brain to measure distance traveled using internal signals rather than external landmarks.

This research was conducted by scientists at the Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience (MPFI) and published in the journal Nature Communications. Their findings offer valuable insight into how the brain performs a process known as path integration, and why this ability is often one of the first to decline in people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Understanding Path Integration and Why It Matters

Path integration is the brain’s ability to keep track of position by continuously monitoring movement—such as steps taken, speed, and turns—rather than relying on sights, sounds, or smells. In everyday life, this ability allows humans and animals to navigate familiar environments even in complete darkness.

Scientists have long known that the hippocampus, a brain region essential for memory and navigation, plays a major role in this process. Traditionally, research has focused on place cells, neurons that become active when an animal is in a specific location. However, most previous studies were conducted in environments filled with sensory cues, making it difficult to determine whether neurons were responding to actual position or to visual landmarks.

The MPFI research team wanted to strip navigation down to its basics and find out how the brain tracks distance when almost all sensory information is removed.

How the Experiment Was Designed

To achieve this, the researchers trained mice to run a specific distance in a gray virtual reality environment that lacked visual landmarks. The mice received a reward only after traveling the correct distance. Because there were no meaningful environmental cues, the animals had to rely entirely on their own movement to judge how far they had gone.

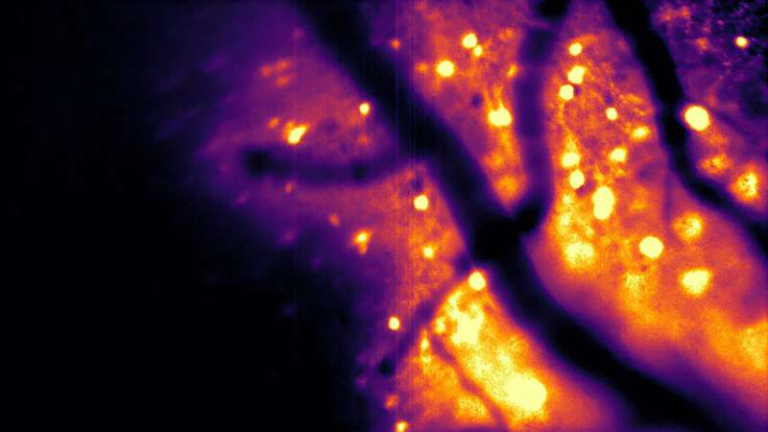

While the mice performed this task, the scientists recorded tiny electrical signals—known as neuronal spikes—from thousands of neurons simultaneously. This allowed the team to observe large-scale activity patterns in the hippocampus as the animals navigated.

The researchers then used computer modeling and data analysis to decode these neural signals and uncover the rules the brain uses to measure distance.

A New Neural Code for Distance

What the scientists found was striking. Instead of most hippocampal neurons representing specific places or moments in time, the majority followed one of two opposing activity patterns that together formed a code for distance.

The first group of neurons showed a sharp increase in activity when the animal started moving. This activity then gradually decreased as the mouse traveled farther. These neurons appeared to mark the start of movement, signaling that distance counting had begun.

The second group displayed the opposite pattern. Their activity dropped when movement began but then steadily increased as the animal continued running. These neurons effectively tracked progress along the route.

Together, these two patterns formed a two-phase neural code:

- A rapid change in activity signaling the onset of movement

- A slower, gradual ramping of activity that represented distance traveled

Importantly, neurons ramped up or down at different rates, allowing the brain to track both short and long distances with precision.

Why This Discovery Is Different From Past Findings

This study marks the first time distance has been shown to be encoded in the hippocampus in a way that is distinct from classic place-based coding. While place cells activate at specific locations, these newly identified neurons encode distance and time continuously through ramping activity.

This discovery expands the understanding of hippocampal function, showing that it uses multiple strategies simultaneously to support navigation and memory. Rather than relying solely on static location markers, the brain also keeps a running tally of movement itself.

What Happens When This System Is Disrupted

To confirm that these neural patterns were essential for navigation, the researchers disrupted the circuits responsible for generating the ramping activity. When this happened, the mice struggled to perform the task correctly. They frequently searched for the reward in the wrong location and showed clear difficulty judging distance.

This demonstrated that the ramping activity patterns were not just correlated with navigation—they were necessary for accurate distance estimation.

Links to Memory and Alzheimer’s Disease

The implications of this research go beyond navigation. The hippocampus is also crucial for forming memories, especially memories that unfold over time. By understanding how the brain tracks distance and duration during movement, scientists gain insight into how moment-to-moment experiences are stitched together into coherent memories.

This is particularly important for understanding Alzheimer’s disease. One of the earliest symptoms reported by patients is spatial disorientation—getting lost in familiar places or not remembering how they arrived somewhere. The ability to integrate distance and time during movement often deteriorates early in the disease.

By identifying the specific neural mechanisms behind path integration, this research may help explain why these symptoms appear so early and could eventually guide strategies for early detection or intervention.

Additional Context: Distance Coding in the Brain

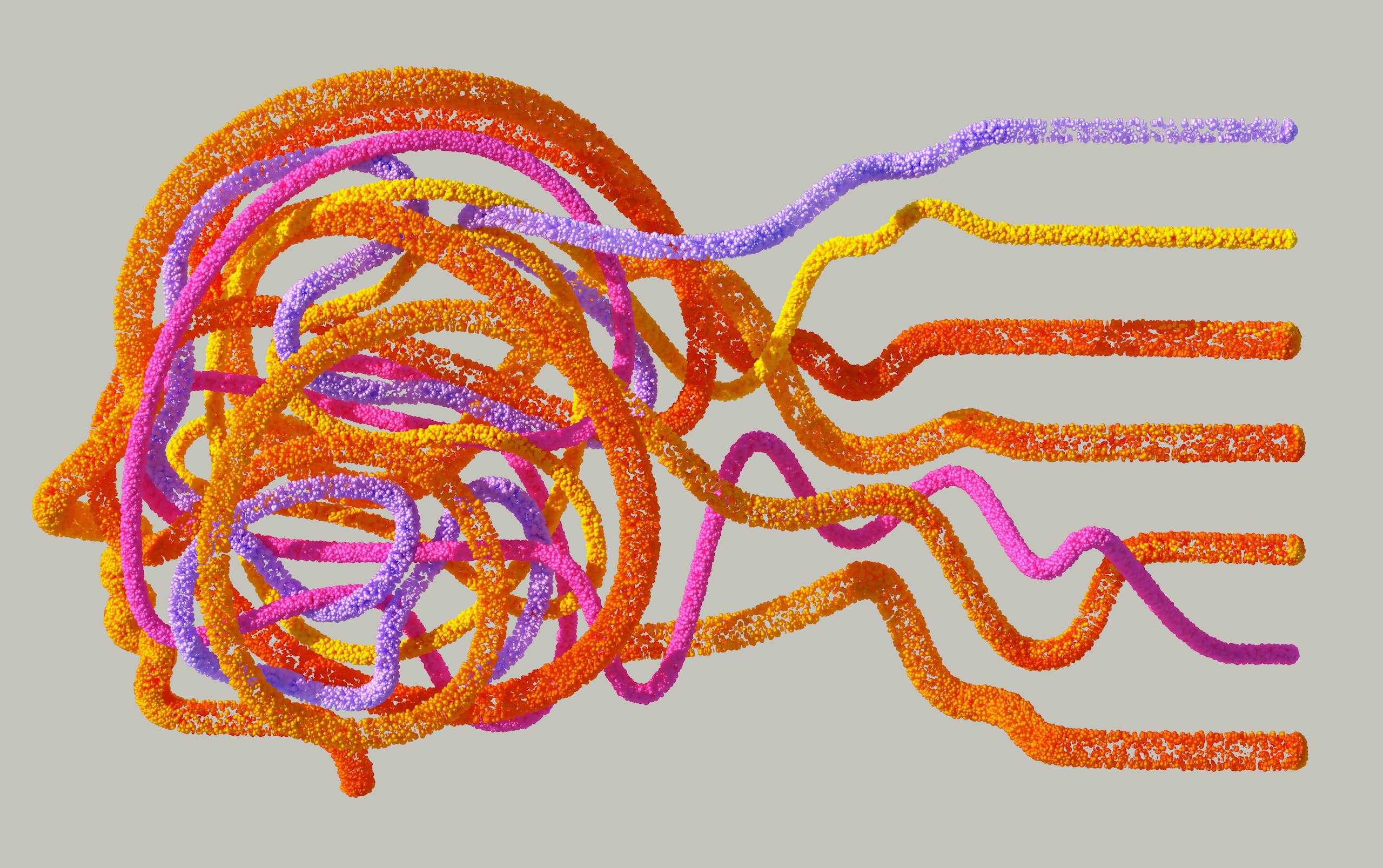

Other studies have shown that distance estimation is not limited to the hippocampus alone. Regions such as the medial entorhinal cortex, which contains grid cells, are also involved in spatial navigation. Grid cells create repeating geometric patterns that help represent space, while hippocampal ramping neurons appear to provide a more dynamic measure of distance and time.

Together, these systems form a multi-layered navigation network, allowing the brain to adapt to environments with or without sensory cues.

Why This Research Is Important

This study provides clear evidence that the brain has an internal system for measuring distance that functions independently of vision. Key takeaways include:

- The brain can track distance using internal movement signals alone

- The hippocampus encodes distance using ramping neural activity

- Disrupting this system leads to navigation errors

- The findings may help explain early cognitive symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease

By revealing how the brain performs this fundamental task, the research opens new avenues for understanding memory, navigation, and neurological disorders.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-67038-3