How Citrin Deficiency Reveals a Surprising Link Between Sweet Aversion and Fatty Liver Disease

Scientists at City of Hope National Medical Center have uncovered a fascinating and unexpected connection between a rare genetic disorder and two seemingly unrelated traits: fat buildup in the liver and a strong aversion to sweets and alcohol. The condition at the center of this discovery is citrin deficiency (CD), a disorder that disrupts how the liver converts nutrients into usable energy. The findings, published in Nature Metabolism, not only deepen scientific understanding of this rare disease but also offer fresh insights into fatty liver disease, a condition affecting more than 1 billion people worldwide.

At the heart of this research is a simple but powerful idea: studying rare metabolic disorders can reveal fundamental biological mechanisms that also operate in much more common diseases.

What Is Citrin Deficiency and Why Does It Matter?

Citrin deficiency is a rare inherited metabolic disorder caused by mutations in the SLC25A13 gene. This gene encodes a protein called citrin, which plays a crucial role in the liver’s ability to shuttle molecules involved in energy production between different parts of the cell. When citrin doesn’t work properly, the liver struggles to efficiently convert food into energy.

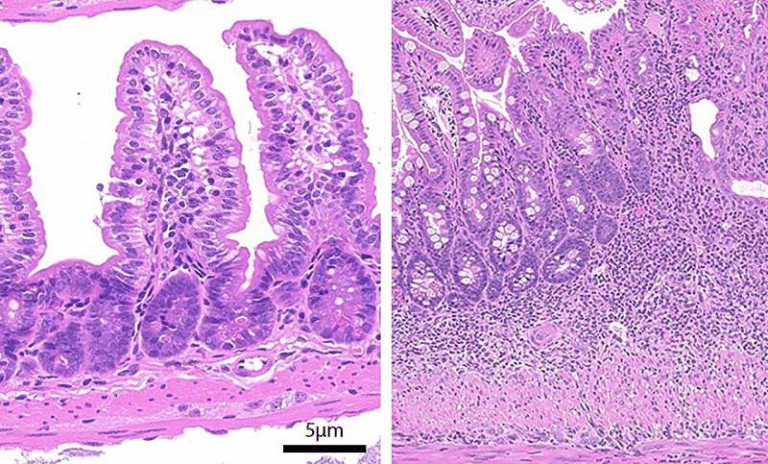

One of the most puzzling aspects of CD is its clinical profile. Most people with citrin deficiency are lean, yet they frequently develop metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly known as fatty liver disease. Even more intriguingly, people with CD often share a natural dislike for sweets and alcohol, something that stands in stark contrast to typical metabolic disorders linked to obesity.

These odd patterns caught the attention of Charles Brenner, Ph.D., an internationally recognized biochemist and the Alfred E. Mann Family Foundation Chair in Diabetes and Cancer Metabolism at City of Hope. Brenner and his team saw CD as a unique opportunity to understand why the liver sometimes chooses to store fat instead of burning it, even in people who are not overweight.

Lean Fatty Liver Disease: A Hidden Global Problem

Fatty liver disease is usually associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. However, hundreds of millions of lean individuals worldwide also have fatty liver disease, often without knowing it. This “lean MASLD” has been poorly understood, largely because it does not fit the classic metabolic risk profile.

By studying citrin deficiency, researchers were able to model a condition where fatty liver develops without obesity, helping to separate the effects of excess body fat from the liver’s own metabolic decision-making. This approach mirrors how rare genetic forms of cancer have historically helped scientists uncover mechanisms that apply to much broader populations.

The Central Discovery: G3P Changes the Liver’s Behavior

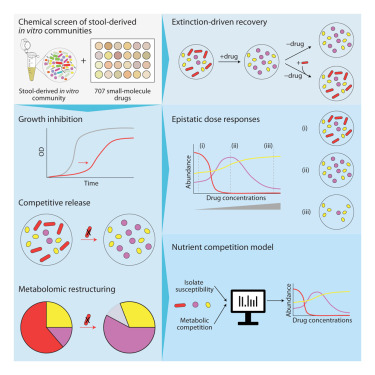

The research team identified a small but critical molecule at the center of the process: glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P). In healthy metabolism, G3P is a normal intermediate involved in energy production and fat metabolism. In citrin deficiency, however, impaired energy pathways cause G3P to accumulate inside liver cells.

This buildup turned out to be far more than a metabolic byproduct. The researchers discovered that G3P directly activates a protein called ChREBP (carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein). ChREBP is a transcription factor, meaning it controls which genes are turned on or off in the cell.

When activated by G3P, ChREBP switches on genes that drive fat synthesis in the liver while simultaneously shutting down fat-burning pathways. This explains why fat accumulates in the liver of people with CD, even though they are lean and not overeating.

What surprised scientists most is that G3P had never before been identified as a direct activator of ChREBP. This finding helps resolve a long-standing mystery in metabolism: why both high carbohydrate intake and carbohydrate deprivation, such as during ketogenic diets, can lead to similar stress responses in the liver.

FGF21: The Hormone That Changes Cravings

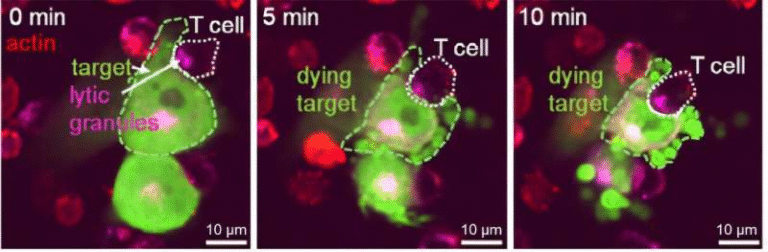

The story doesn’t stop with fat buildup. Activation of ChREBP by G3P also leads to increased production of FGF21 (fibroblast growth factor 21), a hormone released by the liver during metabolic stress.

FGF21 has been known for years to play a role in regulating energy balance, but this study helps clarify its broader effects. Elevated FGF21 levels send signals to the brain that reduce cravings for sweets and alcohol. This provides a clear biological explanation for one of the most distinctive features of citrin deficiency: the strong, often lifelong aversion to sugary foods.

Importantly, FGF21 is not unique to CD. High levels of this hormone are seen in many metabolic states, including fasting, ketogenic diets, and certain liver diseases. By linking G3P accumulation, ChREBP activation, and FGF21 production, the researchers mapped out a unified pathway that explains how the liver responds to different types of metabolic stress.

Why This Matters for MASLD and Public Health

MASLD is a major global health issue, increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and liver cancer. Despite its prevalence, there are currently no widely effective medications that directly target the root metabolic causes of the disease.

This study suggests several promising therapeutic directions:

- Targeting the G3P–ChREBP pathway could help prevent the liver from switching into fat-storage mode.

- Modulating this pathway might also restore fat-burning capacity in the liver.

- FGF21-based therapies, or drugs that mimic its effects, could help reduce cravings for sweets and alcohol while improving metabolic health.

Notably, some pharmaceutical companies are already exploring FGF21 analogs for obesity and metabolic disease. The new findings provide strong mechanistic support for these efforts and suggest that benefits may extend beyond weight loss to liver health and dietary behavior.

Why Rare Diseases Can Unlock Big Discoveries

One of the most important takeaways from this research is the value of studying rare genetic disorders. Citrin deficiency affects a relatively small number of people, but it exposes fundamental rules of liver metabolism that apply far more broadly.

Just as rare inherited cancers helped identify key genes involved in common cancers, CD has revealed why the liver sometimes prioritizes fat storage over energy production in the absence of obesity. This insight could reshape how scientists think about lean metabolic disease, a category that has often been overlooked.

Looking Ahead

The City of Hope team plans to continue exploring how these metabolic pathways can be safely targeted in humans. If successful, future treatments inspired by this work could benefit not only people with citrin deficiency, but also millions living with lean fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrome, or unhealthy dietary cravings driven by underlying metabolic stress.

By turning a rare disorder into a window on common disease, this research brings scientists one step closer to translating metabolic science into real-world health solutions.

Research paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s42255-025-01399-3