Mitochondria May Be the Missing Link Between Mental Health and Brain Function

Psychological stress shows up in many familiar ways. A long, overwhelming year can turn into persistent anxiety. Extended isolation can slowly slide into depression. Old trauma can linger in the background until it interferes with daily life. Scientists have long known that psychological and social experiences shape the brain, but a crucial question has remained unanswered: how do these experiences actually translate into physical changes inside the brain and body?

According to a new review published in Current Directions in Psychological Science, researchers believe they may have found a long-overlooked biological link — mitochondria.

Why mitochondria are now in the mental health spotlight

Mitochondria are usually introduced in school as the powerhouses of the cell, responsible for generating energy. But modern research shows they do much more. Mitochondria are deeply involved in immune signaling, stress responses, inflammation, and neural functioning. Because of this, they are uniquely positioned to respond to environmental and social conditions.

The review, led by psychological scientist Christopher P. Fagundes of Rice University, argues that mitochondria may act as a cellular bridge between psychological experiences and physical health outcomes. In other words, the way stress, loneliness, and trauma affect mental health may begin at the level of mitochondrial function.

Researchers point out that mitochondria are highly sensitive to changes in the body caused by psychosocial stressors. When stress becomes chronic, mitochondria can become less efficient, triggering a cascade of biological effects that extend far beyond energy production.

How stress affects mitochondria

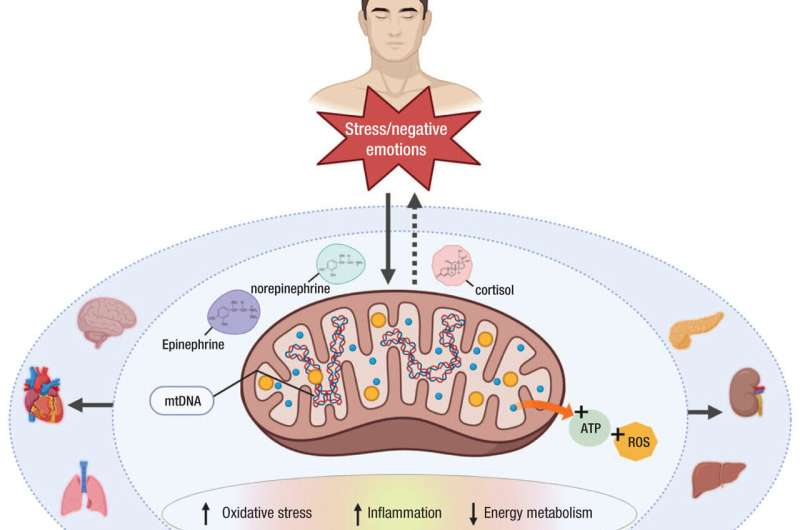

Psychosocial stress activates the body’s neuroendocrine system, releasing stress mediators such as norepinephrine, epinephrine, and cortisol. These chemicals are essential for short-term survival, but when activated repeatedly or over long periods, they can disrupt mitochondrial function.

Altered mitochondrial activity is associated with increased oxidative stress, heightened inflammation, and impaired energy metabolism. These biological changes can affect multiple organs, but the brain is particularly vulnerable.

The brain has an extremely high demand for energy. Neurons rely on mitochondria to fuel neurotransmission, support synaptic plasticity, and maintain healthy communication between brain regions. When mitochondria are underperforming, the brain may struggle to support processes involved in mood regulation, memory, and cognitive flexibility.

Mitochondria and mental health disorders

Alterations in mitochondrial function have been linked to a wide range of mental and neurological conditions, including anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and Alzheimer’s disease. These links extend beyond mental health into physical illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain cancers.

One key area of interest is mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Variations in mtDNA, which plays a critical role in regulating mitochondrial activity, have been associated with a higher risk of anxiety and depression. This suggests that some individuals may be biologically more vulnerable to stress because of differences in mitochondrial functioning.

Researchers emphasize that mitochondria may help explain why two people exposed to similar stressors can have very different psychological outcomes.

The connection between inflammation, stress, and energy

For years, inflammation has been a major focus in mental health research. Elevated inflammatory markers are often found in people with depression, anxiety, and cognitive disorders. However, inflammation alone does not explain why these changes occur.

The new review suggests that mitochondria may be the missing mechanistic link. Chronic stress can gradually reduce mitochondrial efficiency, disrupting the body’s energy balance and increasing inflammatory signaling. This combination may help explain symptoms such as fatigue, brain fog, low motivation, and emotional dysregulation.

Rather than viewing inflammation as the root cause, researchers propose that mitochondrial dysfunction may sit upstream, driving both inflammation and changes in brain signaling.

Potential interventions that support mitochondrial health

While the idea that stress can damage mitochondria sounds concerning, there is encouraging news. Mitochondria are not only vulnerable — they are also responsive to positive interventions.

Among all known strategies, exercise shows the strongest and most consistent benefits. Aerobic and endurance training increase mitochondrial number and improve mitochondrial enzyme activity. This may be one of the biological pathways linking regular physical activity to better mental and physical health.

Other interventions are being explored, though evidence is still emerging. Intensive mindfulness programs have been shown to reduce anxiety while altering certain markers of mitochondrial activity, even when other stress indicators remain unchanged. Psychotherapy has been associated with increases in mitochondrial numbers in individuals with PTSD, although these changes did not directly correlate with symptom improvement.

These findings suggest that while psychological interventions may influence mitochondria, the relationship is complex and not yet fully understood.

Loneliness, social isolation, and mitochondria

Loneliness has become a major public health concern, and researchers believe it may have direct biological consequences. Social isolation is associated with increased stress, reduced physical activity, and heightened inflammation — all factors that can negatively affect mitochondrial health.

A feedback loop may emerge. Loneliness can increase anxiety, which makes social engagement more difficult. Reduced activity and social withdrawal may further weaken mitochondrial function, leading to lower energy levels and reduced resilience. Breaking this cycle becomes increasingly challenging over time.

At present, few studies have directly examined whether improving social support leads to measurable improvements in mitochondrial function. Researchers see this as a promising area for future investigation.

Why this research matters

The idea that mitochondria link psychological experiences to physical health represents a shift in how mental health is studied. Instead of focusing only on symptoms or broad biological markers, scientists are moving toward cell-level explanations.

This approach could lead to new biomarkers for mental health risk, better identification of stress vulnerability, and more targeted interventions. Understanding how mitochondria respond to psychological experiences may also help explain why mental and physical illnesses so often occur together.

Rather than replacing existing theories, mitochondrial research adds another layer of understanding. Inflammation tells researchers that something is happening. Mitochondria may explain why it is happening at the cellular level.

Looking ahead

Researchers emphasize that this field is still developing. More studies are needed to clarify how different stressors affect mitochondrial function, how long these changes last, and which interventions are most effective. There is also growing interest in how mitochondrial health early in life may influence long-term mental health outcomes.

What is clear is that mitochondria are no longer seen as passive energy producers. They are active participants in how the body responds to stress, adapts to social environments, and maintains mental health.

As research continues, mitochondria may become a central focus in understanding — and eventually treating — a wide range of mental and physical disorders.

Research paper:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/09637214251380214