Cement Quietly Absorbs Millions of Tons of Carbon Dioxide Each Year and Scientists Are Finally Measuring It Properly

Cement is everywhere. It holds together our homes, bridges, roads, sidewalks, and entire cities. It is also one of the largest contributors to global carbon dioxide emissions. But researchers are now drawing attention to a lesser-known side of this material: cement does not just emit CO₂, it also absorbs it over time. A new study from the MIT Concrete Sustainability Hub shows that this quiet, slow process removes millions of tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere every year, and until now, it has not been fully measured at a national scale.

The study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, provides the most detailed, bottom-up analysis so far of how cement-based materials take in carbon dioxide across entire countries. The researchers focused on the United States and Mexico, revealing striking differences in how construction practices influence carbon uptake.

How Cement “Breathes In” Carbon Dioxide

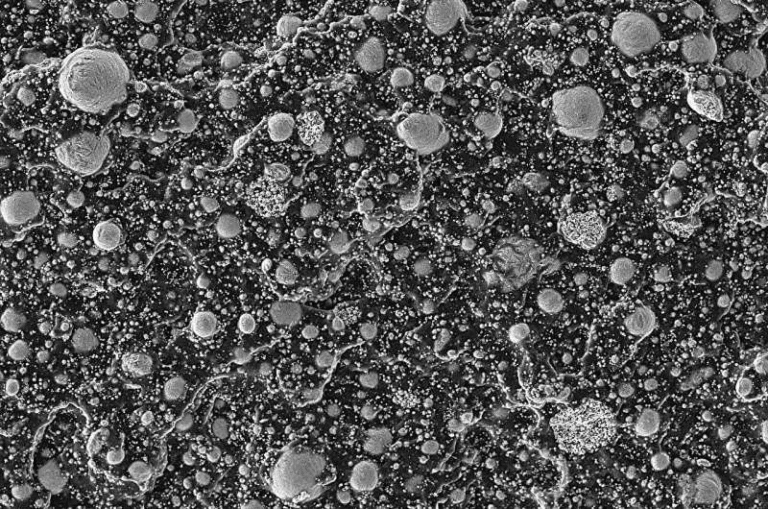

The process behind cement’s carbon absorption is well understood chemically. Cement is a key ingredient in concrete and mortar. Over time, carbon dioxide from the air enters tiny pores in these materials. Once inside, the CO₂ reacts with calcium-rich compounds left over from cement production. This reaction forms calcium carbonate, essentially limestone, which permanently locks the carbon into a stable mineral form.

This process is called carbonation, and scientists have known about it for decades. What has been missing is a reliable way to calculate how much CO₂ this process removes at a large scale, across millions of buildings and infrastructure elements that all behave differently.

A highway pavement in Texas, a concrete apartment building in Mexico City, and a foundation slab buried under snow in Alaska all absorb carbon dioxide at different rates. Factors like climate, geometry, exposure to air, material composition, and age play major roles. This complexity has made national-level estimates extremely difficult.

A New Way to Measure Carbon Uptake at Scale

Instead of trying to simulate every individual structure, the MIT research team took a smarter approach. They developed hundreds of representative “archetypes” that stand in for common cement-based elements such as slabs, walls, pavements, beams, columns, and masonry units.

Each archetype represents a typical design with known dimensions, materials, and exposure conditions. The researchers then modeled how each one absorbs carbon dioxide under different climates and usage scenarios. By combining these models with construction data and building-stock statistics, they were able to estimate carbon uptake across every U.S. state and across Mexico.

This approach allowed the team to calculate not just total carbon uptake, but also why uptake differs from place to place.

What the Numbers Show in the United States

According to the study, cement in U.S. buildings and infrastructure absorbs more than 6.5 million metric tons of CO₂ every year. That number is significant because it represents about 13 percent of the process emissions from U.S. cement manufacturing.

Process emissions come from the chemical reaction that converts limestone into clinker, the key component of cement. These emissions are unavoidable unless alternative chemistries are used. The fact that a measurable portion is naturally reabsorbed over time changes how the overall carbon footprint of cement should be understood.

The researchers found that construction trends play a major role. States with higher rates of recent construction tend to have more actively carbonating cement, because newer surfaces are more exposed and reactive. Older structures still absorb carbon dioxide, but the rate slows as carbonation progresses inward from exposed surfaces.

Why Mexico Absorbs So Much CO₂ with Less Cement

One of the most striking findings comes from Mexico. Even though Mexico uses about half as much cement as the United States, its buildings and infrastructure absorb around 5 million metric tons of CO₂ per year. That means Mexico achieves roughly three-quarters of the U.S. carbon uptake with far less cement consumption.

The reason lies in construction practices. Mexico relies more heavily on mortar, concrete masonry units (CMUs), and lower-strength concrete. Mortar, which is more porous than dense structural concrete, absorbs carbon dioxide up to an order of magnitude faster. Mexico also uses more bagged cement mixed on-site, which leads to material properties that favor carbonation.

As a result, carbon uptake in Mexico offsets about 25 percent of its cement manufacturing emissions, compared to a smaller fraction in the U.S.

The Key Factors That Control Carbon Uptake

The study identified four main drivers of carbon uptake in cement-based materials:

- Type of cement used

- Type of product, such as concrete, mortar, or masonry units

- Geometry of the structure, which affects surface area exposed to air

- Climate and exposure conditions, including temperature and humidity

Even within a single building, different elements can absorb carbon dioxide at rates that vary by as much as five times.

One especially important factor is the ratio of mortar to concrete. Regions that use more mortar see significantly higher carbon uptake relative to emissions, simply because mortar allows CO₂ to move through it more easily.

Opportunities to Increase Carbon Uptake Safely

The researchers emphasize that carbon uptake should not be treated as a free pass for emissions. However, they do point out that uptake can be enhanced without harming performance, especially in elements that do not rely on steel reinforcement.

Design choices can make a real difference. Increasing surface area exposed to air accelerates carbonation. This can be done by avoiding unnecessary surface coverings like paint or tile, or by choosing structural designs such as waffle slabs, which have a higher surface-to-volume ratio.

Another opportunity lies in avoiding over-engineered concrete mixes. Using stronger, denser concrete than required not only increases cement use but also slows carbon uptake. Matching material strength more closely to actual needs can reduce emissions and increase long-term absorption.

That said, caution is needed. Faster carbonation can increase the risk of steel corrosion in reinforced concrete if not properly managed. Any strategy to enhance uptake must balance durability and safety.

Why This Matters for Climate Accounting

One of the most important implications of this research is for national and international carbon inventories. Many current reporting frameworks, including those used globally, rely on simplified assumptions about cement carbonation. According to the researchers, some of these assumptions may overestimate uptake in certain contexts and underestimate it in others.

By providing a detailed, bottom-up methodology, the study offers a path toward more accurate reporting, including potential updates to guidelines used by organizations such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Understanding what existing buildings are already doing to absorb carbon dioxide helps create a more realistic picture of the built environment’s true climate impact.

Cement, Carbon, and the Bigger Picture

Cement production accounts for around 8 percent of global human-caused CO₂ emissions, making it a critical sector for decarbonization. Innovations like low-carbon cements, alternative binders, and carbon capture technologies remain essential.

At the same time, this study shows that cement is already participating in the carbon cycle in meaningful ways. Recognizing and accurately measuring this process does not solve the emissions problem, but it does improve how progress is tracked and how strategies are evaluated.

The approach developed by the MIT team can be applied to other countries by combining building-stock data with cement production statistics. It may also guide future designs that safely maximize carbon uptake while reducing emissions upfront.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2515116122