Self-Healing Nuclear Fuel Could Make Reactors Safer and Cut Down Radioactive Waste

Nuclear power is often described as one of the cleanest large-scale energy sources available today. It produces near-zero carbon emissions during operation, requires far less land than wind or solar, and can deliver reliable power around the clock. Yet despite these advantages, nuclear energy still faces major technical and public acceptance challenges. One of the biggest issues lies deep inside the reactor itself: the fuel degrades over time under intense radiation, creating safety risks and large amounts of long-lived radioactive waste.

A new international research effort may have found a promising way to tackle this problem. Scientists have developed a novel approach to nuclear fuel design that could allow fuel to last longer, remain more stable, and even “heal” itself during operation. If successfully implemented, this technology could significantly improve reactor safety and reduce the amount of nuclear waste produced.

Why Current Nuclear Fuel Struggles Inside Reactors

Most nuclear reactors rely on fuel materials that must endure extreme conditions. Inside a reactor core, fuel is constantly bombarded by radiation from nuclear fission. Over time, this radiation causes the fuel to swell and deform. This is especially true for metallic nuclear fuels, which are attractive for advanced reactors but are prone to structural changes under irradiation.

As the fuel swells, it begins to press against the cladding, the protective outer layer that surrounds each fuel rod. The cladding’s job is crucial: it seals radioactive material inside and prevents fission byproducts from escaping into the reactor coolant. When the fuel presses against it, chemical reactions and mechanical stress can weaken the cladding, making it brittle and more likely to fail. Once cladding performance is compromised, the fuel must be removed from the reactor, even if it still contains usable energy.

This limitation reduces fuel efficiency and contributes to the growing stockpile of spent nuclear fuel, which remains radioactive for thousands of years.

A New Idea: Nanoparticles Inside the Fuel

To address this issue, a team of researchers led in part by Samrat Choudhury, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Mississippi, explored a new strategy: engineering the fuel at the nanoscale.

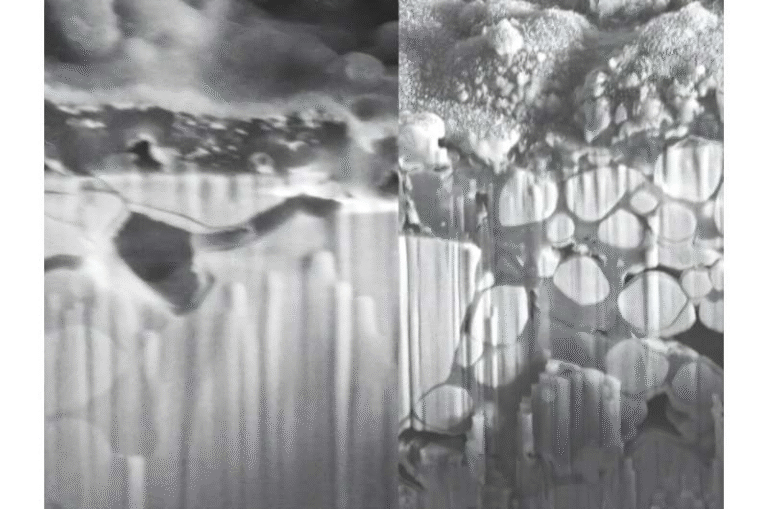

Their research focused on embedding uranium nitride (UN) nanoparticles directly into a metallic nuclear fuel matrix. Uranium nitride is already known in nuclear science for its high uranium density and excellent thermal conductivity, both desirable traits for advanced reactor fuels. But the researchers discovered something even more interesting.

These tiny UN particles can act as traps for fission products, the atoms created when uranium splits during nuclear reactions. Normally, these fission products migrate through the fuel and eventually reach the cladding, where they cause damage. By introducing UN nanoparticles, the researchers created interfaces within the fuel that capture and hold these harmful byproducts before they can spread.

How “Self-Healing” Nuclear Fuel Works

The concept behind this new fuel design is often described as self-healing, though not in the science-fiction sense. Instead, the healing happens at the microscopic level.

When fission occurs, it creates defects in the fuel’s crystal structure, such as vacancies and interstitial atoms. These defects allow fission products to move freely. The interfaces between uranium nitride nanoparticles and the surrounding metallic fuel act as defect sinks, absorbing both structural damage and fission byproducts. This helps maintain the integrity of the fuel over longer periods.

The researchers compared this behavior to oxide-dispersion-strengthened steels, materials already used in extreme environments that rely on tiny particles to stabilize their structure under stress.

Building on Earlier Findings

This 2025 study builds on earlier work published in 2024, where the team demonstrated that forming uranium nitride nanoparticles inside metallic fuel could effectively capture fission gases. In the latest study, the focus shifted to solid fission products and how the nanoparticle interfaces interact with them.

The results showed that these engineered interfaces are highly effective at trapping the particles responsible for fuel degradation. This significantly slows down the processes that normally lead to swelling, cladding damage, and early fuel failure.

Why This Matters for Nuclear Waste

One of the most persistent criticisms of nuclear energy is the amount of radioactive waste it generates. Spent fuel remains hazardous for extremely long periods, and managing it safely is expensive and politically sensitive.

By allowing fuel to stay in the reactor longer and achieve higher burnup, this new approach could reduce the volume of spent fuel produced. Higher burnup means more energy is extracted from the same amount of uranium, improving efficiency and slowing the accumulation of nuclear waste.

Reducing waste doesn’t just ease storage concerns. It also lowers costs and could make nuclear energy more acceptable to the public, which has long been wary of radioactive byproducts.

Impact on Nuclear Energy Adoption

In the United States, nuclear power currently supplies about 20% of electricity, despite its low emissions and reliability. Technical improvements like this could play a role in expanding nuclear energy’s share of the power grid.

Better fuel performance means reactors can operate longer between refueling outages, improve overall efficiency, and reduce long-term risks associated with fuel degradation. These advantages are especially important for next-generation reactors, including small modular reactors and advanced fast reactors, which aim to be safer and more economical than traditional designs.

What Comes Next for This Technology

While the findings are promising, the research is still at an early stage. So far, testing has focused on laboratory conditions and simulations designed to mimic the intense environment inside a reactor. The next critical step is real-world irradiation testing in research reactors.

Such testing requires significant funding, time, and collaboration with industry partners. Nuclear fuel technologies must meet extremely strict safety and regulatory standards before they can be used commercially. Researchers estimate that bringing this type of fuel from the lab to actual power plants could take many years, but they see this work as a vital first step.

Understanding Uranium Nitride as a Fuel Material

Uranium nitride has long attracted interest in nuclear engineering. Compared to the commonly used uranium dioxide fuel, UN offers higher thermal conductivity, which helps remove heat more efficiently from the reactor core. This can improve safety margins and reduce the risk of overheating.

UN also has a higher uranium density, meaning more fuel can be packed into the same volume. These properties make it particularly appealing for advanced reactors designed to operate at higher temperatures or under more demanding conditions.

The challenge has always been stability under irradiation. By combining UN nanoparticles with metallic fuel, researchers may have found a way to unlock the best qualities of both materials.

A Step Toward Safer, More Efficient Nuclear Power

This research highlights how materials science at the nanoscale can address long-standing problems in nuclear energy. By redesigning fuel from the inside out, scientists are finding ways to make reactors safer, more efficient, and more sustainable.

While there is still a long road from laboratory success to commercial use, the idea of self-healing nuclear fuel represents an important shift in how engineers think about reactor materials. If future testing confirms these results, this technology could play a meaningful role in the future of clean energy.

More information about the study can be found in the research paper published in Advanced Materials Interfaces:

https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.202500592