MIT Researchers Build an AI-Powered Robot That Designs and Assembles Objects From Simple Text Prompts

Researchers from MIT, along with collaborators from Google DeepMind and Autodesk Research, have developed an AI-driven robotic system that can design and physically build real-world objects based on plain-language instructions from users. Instead of relying on complex computer-aided design (CAD) software, the system allows people to describe what they want using everyday language, such as “make me a chair,” and then refines, designs, and assembles the object automatically.

This work represents a major step toward making physical design and fabrication more accessible, interactive, and sustainable, especially for people without professional engineering or design backgrounds.

Why Traditional CAD Tools Fall Short for Many People

CAD systems are widely used across industries to design everything from furniture to aircraft parts. However, these tools come with a steep learning curve. They require extensive training, precise modeling skills, and an understanding of detailed geometric constraints. As a result, CAD software often feels more suited for final production than for early-stage brainstorming or rapid experimentation.

The MIT-led research team aimed to remove these barriers by creating a system that allows humans to communicate design intent naturally, while AI and robotics handle the complexity of geometry, component placement, and physical assembly.

A Two-Stage AI System That Turns Words Into Objects

The system works through a carefully structured, end-to-end pipeline that combines generative AI, vision-language reasoning, and robotic assembly.

In the first stage, a 3D generative AI model converts the user’s text prompt into a three-dimensional mesh. This mesh captures the overall geometry of the object, such as the shape of a chair or shelf. While text-to-3D models have advanced significantly in recent years, they typically generate monolithic shapes that lack the detailed component information required for physical construction.

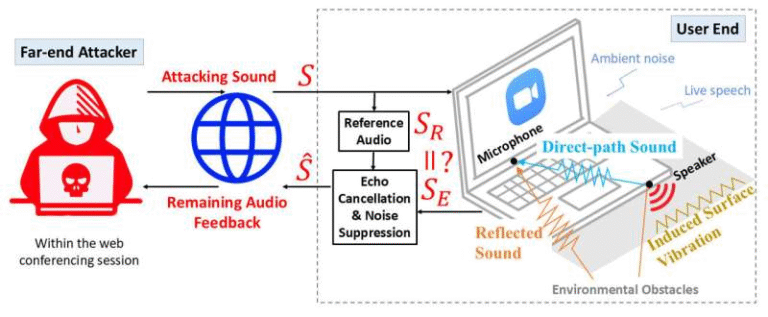

To solve this, the researchers introduced a second AI component: a vision-language model (VLM). This model acts as both the “eyes” and “brain” of the robot. It analyzes the 3D geometry while also reasoning about how objects function in the real world.

The VLM determines how prefabricated components should be arranged to form a usable object. In the current system, these components fall into two categories: structural components, which provide strength and stability, and panel components, which create functional surfaces such as seats, shelves, or backrests.

Understanding Function, Not Just Geometry

One of the most impressive aspects of the system is its ability to reason about function, not just shape. For example, when generating a chair, the VLM can identify which surfaces should support sitting and leaning. It assigns panel components to the seat and backrest while leaving other areas uncovered if they do not serve a functional purpose.

The model accomplishes this by labeling different surfaces of the 3D mesh with semantic descriptors like “seat” or “backrest.” These labels are then used to determine where panels should be placed. This reasoning process is iterative and informed by the vast number of objects the model has encountered during training.

The result is a design that reflects how humans intuitively expect objects to work, rather than one that follows simplistic geometric rules.

Human-in-the-Loop Design Refinement

The system is not fully autonomous, and that is by design. Users remain actively involved throughout the process and can refine the object by providing additional feedback. For instance, a user might say they want panels only on the backrest and not on the seat, or request a different configuration entirely.

This human-AI co-design approach helps narrow the enormous design space and ensures the final object aligns with individual preferences. Rather than attempting to build a single “ideal” model for everyone, the system adapts dynamically to user input.

This feedback-driven loop also gives users a sense of ownership over the final product, even though much of the technical work is handled by AI.

From Digital Design to Physical Assembly

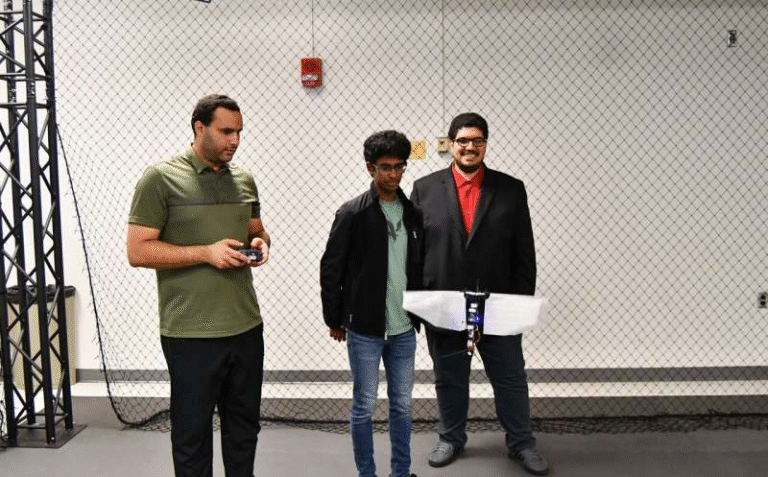

Once the 3D design is finalized, a robotic system takes over and physically assembles the object using the prefabricated components. These components are designed to be modular, meaning they can be disassembled and reused in different configurations.

The researchers demonstrated the system by fabricating real furniture, including chairs and shelves, using only two types of components. Because the parts are reusable, the approach reduces material waste compared to traditional fabrication methods where objects are built once and discarded.

This modularity also opens the door to rapid prototyping, experimentation, and redesign without starting from scratch.

User Study Results Show Strong Preference

To evaluate the quality of the designs, the research team conducted a user study comparing their AI-driven approach with two baseline methods. One baseline placed panels on all upward-facing horizontal surfaces, while the other placed panels randomly.

The results were striking. More than 90 percent of participants preferred the objects created by the AI-driven system. Users consistently found these designs more intuitive, functional, and visually coherent.

The researchers also asked the vision-language model to explain its decisions. These explanations revealed that the model had developed a meaningful understanding of object use, such as recognizing where people sit or lean on a chair.

Applications Beyond Furniture

While the current demonstrations focus on simple furniture, the researchers emphasize that this is only an initial step. The underlying framework could be extended to much more complex objects, including architectural structures, aerospace components, and other engineered systems.

Future versions of the system may incorporate additional prefabricated parts such as hinges, gears, and moving components, enabling the creation of objects with dynamic functionality. The team is also interested in supporting more nuanced prompts, such as specifying materials like glass or metal.

In the longer term, this technology could enable local, on-demand fabrication in homes or small workshops, reducing the need to ship bulky products from centralized factories.

How Vision-Language Models Are Changing Robotics

Vision-language models are becoming a powerful tool in robotics because they combine visual understanding with language-based reasoning. Unlike traditional robotic systems that rely on rigid rules and preprogrammed instructions, VLMs can adapt to new tasks by interpreting context and intent.

In this project, the VLM’s ability to bridge geometry, language, and function is what makes natural-language-driven fabrication possible. This same approach could influence future developments in robotic manipulation, assembly lines, and human-robot collaboration.

Lowering the Barrier to Making Physical Things

At its core, this research is about democratizing design. By allowing people to communicate with machines the same way they communicate with other humans, the system removes many of the technical hurdles that prevent non-experts from turning ideas into physical objects.

The researchers see this work as a foundation for a future where humans and AI systems collaborate fluidly to design and build the world around them, quickly, sustainably, and creatively.

Research Paper:

Text to Robotic Assembly of Multi-Component Objects using 3D Generative AI and Vision Language Models

https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.02162