A Simple Chemical Additive Could Make Carbon Capture Cheaper and Far More Practical for Industry

Capturing carbon dioxide from industrial facilities is widely seen as one of the most important tools for slowing global climate change, especially in sectors where emissions are hard to eliminate entirely. Industries such as cement, petrochemicals, steel, and fertilizer production release massive amounts of CO₂ as part of their core chemical processes. While carbon capture technologies already exist, they are expensive, energy-hungry, and difficult to scale. Now, chemical engineers at MIT have demonstrated a surprisingly simple modification that could dramatically reduce both the cost and energy demand of industrial carbon capture systems.

The key idea is straightforward: add a common chemical called tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane, more commonly known as tris, to a carbonate-based carbon capture solution. This small change allows carbon dioxide to be captured more efficiently and released at much lower temperatures than conventional systems. The result is a method that could work with waste heat, solar thermal energy, or other low-grade heat sources already available at industrial plants.

Why Carbon Capture Matters So Much

Carbon capture involves separating CO₂ from exhaust gases before it enters the atmosphere. Once captured, the carbon dioxide can either be stored underground in geological formations or used as a raw material for other products. Despite decades of research, only about 0.1 percent of global carbon emissions are currently captured and stored or reused.

One major reason for this low adoption rate is the energy penalty. Most commercial systems rely on chemical solvents that require high temperatures to release the captured CO₂ so the solvent can be reused. Generating that heat is expensive and often involves burning additional fossil fuels, which partially undermines the climate benefits.

This is the bottleneck MIT researchers set out to address.

How Traditional Carbon Capture Works

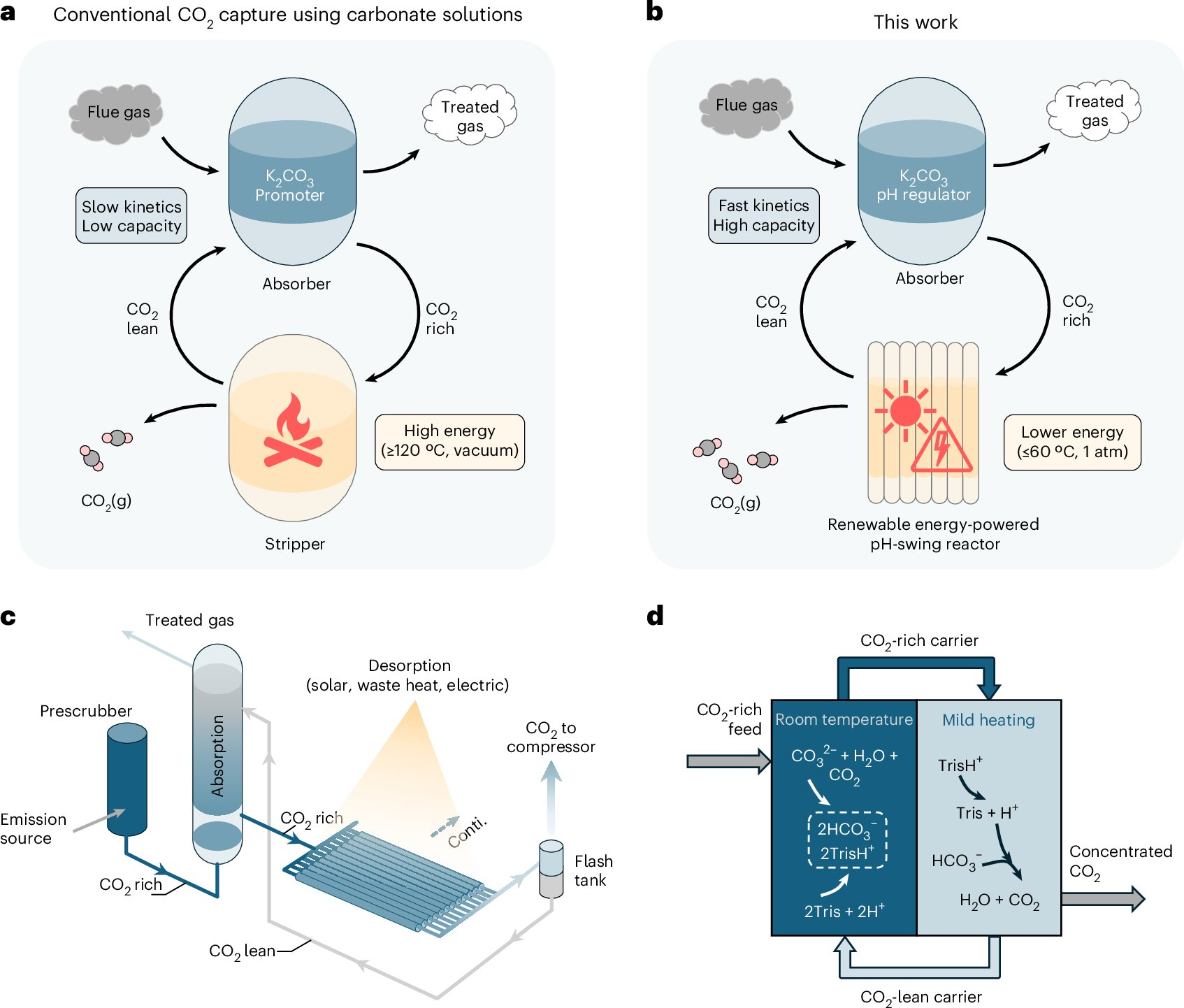

The most common industrial approach uses amine-based solutions. These liquids have a high pH, which allows them to absorb acidic CO₂ from exhaust gases. Another alternative uses carbonate solutions, such as potassium carbonate, which are attractive because they are cheap, chemically stable, and produce negligible emissions themselves.

However, both amines and carbonates suffer from a similar limitation. As CO₂ is absorbed, the pH of the solution drops rapidly. This change in acidity reduces the solution’s ability to continue capturing carbon dioxide. Even more problematic is the regeneration step: releasing the CO₂ typically requires heating the solution to temperatures above 120°C. This step consumes enormous amounts of energy and drives up operating costs.

The Role of Tris in the New System

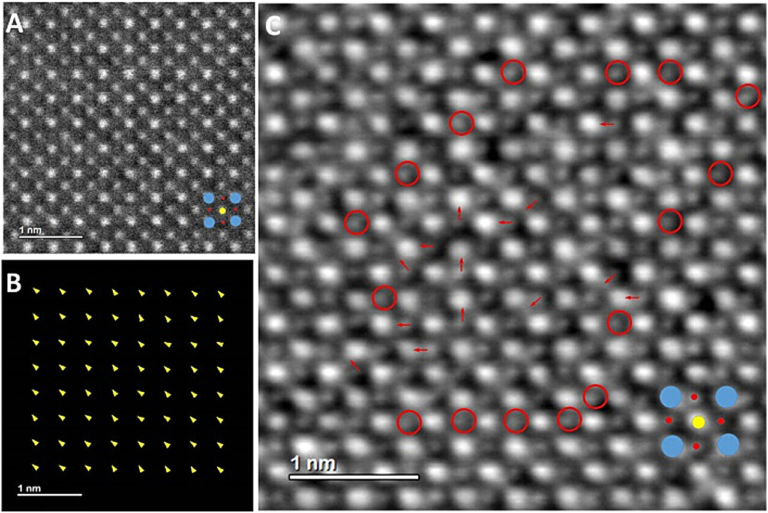

The MIT team discovered that adding tris to a potassium carbonate solution fundamentally changes this behavior. Tris is widely used in laboratory experiments as a pH buffer, meaning it helps stabilize acidity levels. It is also found in everyday products, including some cosmetics and even COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, making it a well-understood and widely available compound.

When CO₂ is absorbed by a carbonate solution, bicarbonate ions form, carrying a negative charge. Positively charged tris molecules balance this charge, preventing the pH from dropping too quickly. As a result, the solution can absorb roughly three times more CO₂ than a carbonate solution without tris.

This alone is a major improvement, but the most striking benefit comes during regeneration.

Releasing CO₂ at Just 60°C

Tris has a second useful property: it is highly sensitive to temperature changes. When the CO₂-rich solution is gently heated to around 60°C (140°F), tris releases protons, causing a rapid drop in pH. This sudden change forces the captured CO₂ to come out of solution as a gas.

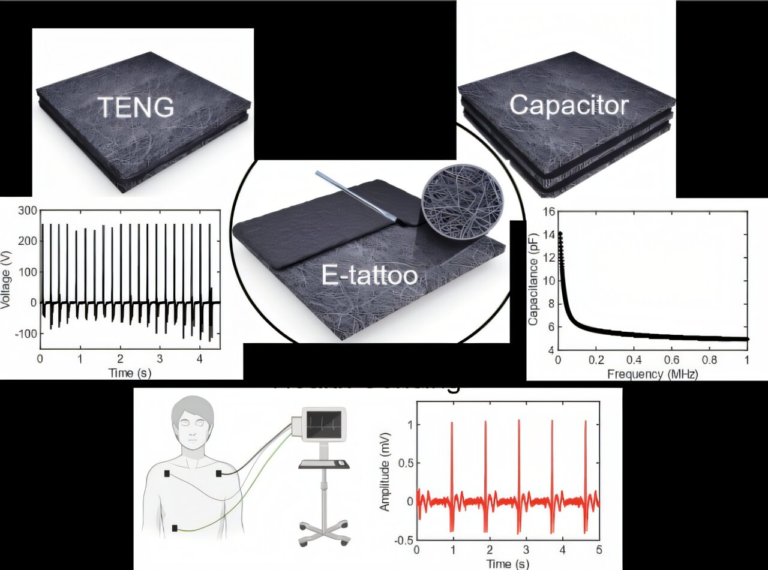

Compared to conventional systems that require temperatures exceeding 120°C, this is a dramatic reduction in energy demand. At 60°C, many industrial facilities can rely on existing waste heat, low-temperature electric heaters, or even solar thermal systems.

The regeneration process also occurs at atmospheric pressure, avoiding the need for vacuum-assisted systems that further increase complexity and cost.

A Continuous and Practical Design

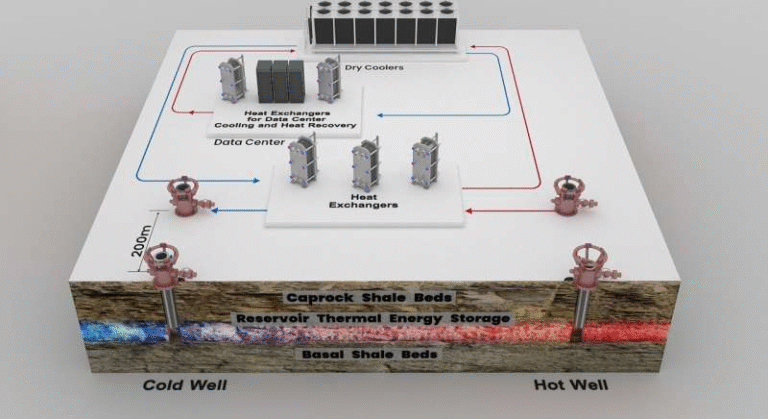

To demonstrate that this approach works beyond the lab, the researchers built a continuous-flow carbon capture reactor. In this setup, CO₂-containing gas is bubbled through a reservoir of the carbonate-tris solution, where the carbon dioxide is absorbed. The solution is then pumped into a regeneration module, gently heated to release a pure stream of CO₂.

Once regeneration is complete, the solution is cooled and returned to the absorption chamber for another cycle. This continuous loop mirrors how industrial systems already operate, reinforcing the idea that the technology could be adopted without a complete redesign of existing infrastructure.

One of the most appealing aspects of the system is its simplicity. Facilities currently using amine-based capture systems could potentially switch to a carbonate-tris solution with minimal changes. This “drop-in” nature could significantly accelerate real-world deployment.

What Happens to the Captured Carbon?

Captured CO₂ can be used in several ways, including the production of fuels, building materials, or specialty chemicals. However, there is a practical limit to how much carbon dioxide can be reused before markets become saturated. As a result, the majority of captured carbon is expected to be stored underground in stable geological formations.

Lowering the cost of capture makes both utilization and storage more feasible, particularly for industries facing growing regulatory pressure to reduce emissions.

Why Carbonates Are So Attractive

Potassium carbonate is often described as a holy grail solvent for carbon capture. It is inexpensive, chemically stable over long periods, and does not degrade easily. Unlike some amines, it produces negligible harmful byproducts and poses fewer environmental risks.

The main drawback has always been its poor performance at low temperatures and the energy required for regeneration. The tris-based pH buffering approach directly addresses both issues, unlocking the potential of carbonates as a truly competitive capture solvent.

Broader Context in Carbon Capture Technology

Carbon capture technologies are often criticized for being too expensive or energy-intensive to make a meaningful dent in global emissions. Innovations like this one show that progress does not always require exotic materials or entirely new systems. Sometimes, small chemical adjustments can have an outsized impact.

By reducing regeneration temperatures and increasing CO₂ uptake, this approach could make carbon capture economically viable for a wider range of facilities, including smaller plants that previously could not justify the cost.

What Comes Next

The research team is now exploring whether other additives could further improve the system by speeding up CO₂ absorption rates or enhancing long-term stability. Scaling the technology to full industrial size and validating its performance over extended operating periods will be the next major steps.

If these results hold at scale, this carbonate-tris system could become a key tool in reducing industrial carbon emissions worldwide.

Research Paper Reference

https://doi.org/10.1038/s44286-025-00313-8