Small Language Models Can Now Tackle Complex Reasoning Tasks Thanks to a New MIT Framework

Researchers at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) have introduced a new way to make small language models far more capable at solving complex reasoning problems—tasks that traditionally required very large, expensive AI systems. The approach, called DisCIPL, challenges the common belief that bigger models are always better when it comes to structured reasoning, constraint-heavy tasks, and real-world planning.

At first glance, modern language models appear highly intelligent. They generate images, answer trivia questions, and solve basic math with ease. However, once they face problems that involve strict rules, multiple constraints, or open-ended decision-making, their limitations become obvious. Tasks like solving Sudoku puzzles, writing text that follows precise formatting rules, designing molecules, or producing mathematical proofs still push most language models beyond their comfort zone.

Small language models struggle especially hard in these scenarios. Large language models can sometimes manage them, particularly when optimized for reasoning, but they are slow, energy-intensive, and costly to run. This trade-off between performance and efficiency is what led the MIT CSAIL team to explore a different strategy altogether.

What DisCIPL Is and Why It Matters

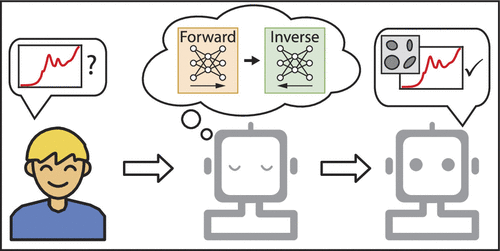

DisCIPL, short for Distributional Constraints by Inference Programming with Language Models, introduces a collaborative setup where multiple models work together instead of relying on a single, massive system. In this framework, one large language model acts as a planner, while several smaller models handle the execution.

Rather than generating the final answer itself, the planner model focuses on strategy. It decides how a problem should be solved, breaks it into smaller steps, and assigns those steps to the smaller “follower” models. These follower models then generate pieces of the solution, guided by strict instructions and constraints.

This structure allows small models to perform tasks that would normally be far beyond their individual capabilities. More importantly, it does so while using far less computing power than state-of-the-art reasoning systems.

The Boss-and-Workers Analogy

One way to understand DisCIPL is to think of it like a project manager overseeing a team. You give the manager a task—say, writing a tightly constrained piece of text or planning a trip within a strict budget. The manager carefully plans how to approach the task, then delegates specific parts of the work to different team members.

In DisCIPL, the “boss” model communicates its plan to the follower models in a precise and formal way. If a follower produces something that does not meet the requirements, the planner steps in, corrects it, or replaces it with a better alternative from another follower.

This approach turns reasoning into a coordinated process, rather than a single model struggling to keep everything in mind at once.

The Role of LLaMPPL

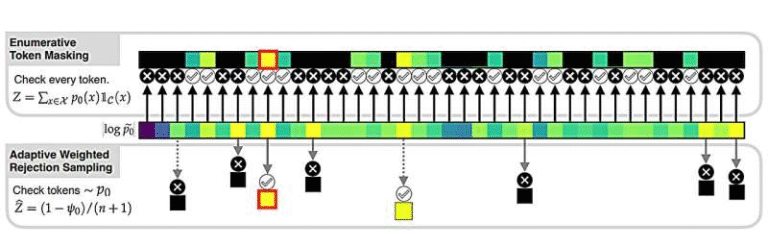

A key technical component behind DisCIPL is LLaMPPL, a programming language developed by MIT’s Probabilistic Computing Project in 2023. LLaMPPL allows researchers to encode rules and constraints directly into instructions that language models can follow.

For example, instead of vaguely asking a model to write a poem with certain constraints, LLaMPPL lets the system specify exact rules such as word counts, line counts, or required keywords at precise positions. These rules guide the follower models and ensure their outputs stay within acceptable bounds.

This method has already been used in other contexts, such as producing error-free code by embedding the syntax rules of a programming language directly into model instructions. DisCIPL applies the same idea to text generation and reasoning.

How the Researchers Tested DisCIPL

To evaluate their framework, the researchers ran a series of experiments involving both synthetic constraints and real-world tasks. In many cases, they used GPT-4o as the planner model and several Llama-3.2-1B models as followers. These Llama models are much smaller and significantly cheaper to run than large reasoning-focused systems.

One test involved generating sentences with extremely specific requirements. For example, a sentence might need to contain exactly 18 words, with certain words appearing at specific positions. DisCIPL handled these challenges with impressive accuracy, producing coherent sentences that followed every rule precisely.

The system was also tested on practical tasks like creating grocery lists within fixed budgets, planning travel itineraries, writing ingredient lists, and drafting grant proposals with strict word limits. Across these benchmarks, DisCIPL consistently outperformed standalone small models and even surpassed GPT-4o operating on its own.

Performance Compared to Leading Reasoning Models

Perhaps the most striking result is how DisCIPL compares to top-tier reasoning systems, such as OpenAI’s o1 model. While o1 performs reasoning directly in text form, DisCIPL “reasons” by generating compact Python-style inference code, which is far more efficient.

According to the researchers, this leads to 40.1% shorter reasoning sequences and an 80.2% reduction in inference cost compared to o1. Since the follower models are between 1,000 and 10,000 times cheaper per token, DisCIPL can scale easily by running many models in parallel without a massive increase in cost.

This efficiency makes DisCIPL particularly attractive in a world where language models are being used more frequently and at larger scales, driving up energy consumption.

Why Smaller Models Working Together Can Win

One of the key takeaways from this research is that coordination matters as much as model size. While large models are powerful, they are not always the most efficient or reliable option for tasks with clear rules and constraints.

DisCIPL shows that by combining multiple smaller models under a strong planning framework, it is possible to achieve performance that rivals or even exceeds much larger systems. This challenges long-standing assumptions about how AI systems should be built and deployed.

Broader Implications for AI Development

Beyond performance gains, DisCIPL opens doors to improved transparency, interpretability, and controllability in language model outputs. Because reasoning is structured and rule-based, it becomes easier to understand why a system produced a particular result.

The researchers see this as part of a broader trend toward auto-formalization, where language models translate natural language tasks into structured representations that can be solved more reliably.

What Comes Next

The MIT CSAIL team plans to expand DisCIPL in several directions. One goal is to make the framework fully recursive, allowing the same model to act as both planner and follower. Another is to apply the approach to mathematical reasoning, where verifying correctness is often difficult.

They are also interested in exploring tasks with fuzzy or subjective preferences, which cannot be encoded as rigid rules as easily. While these experiments may require even larger models, the team acknowledges that such work will be computationally expensive.

Still, DisCIPL already demonstrates that smarter coordination—not just bigger models—can push AI reasoning forward in meaningful ways.

Research paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.07081