A New Computational Model Shows How Cooling and Aging Can Unlock Stronger Lightweight Aluminum Alloys

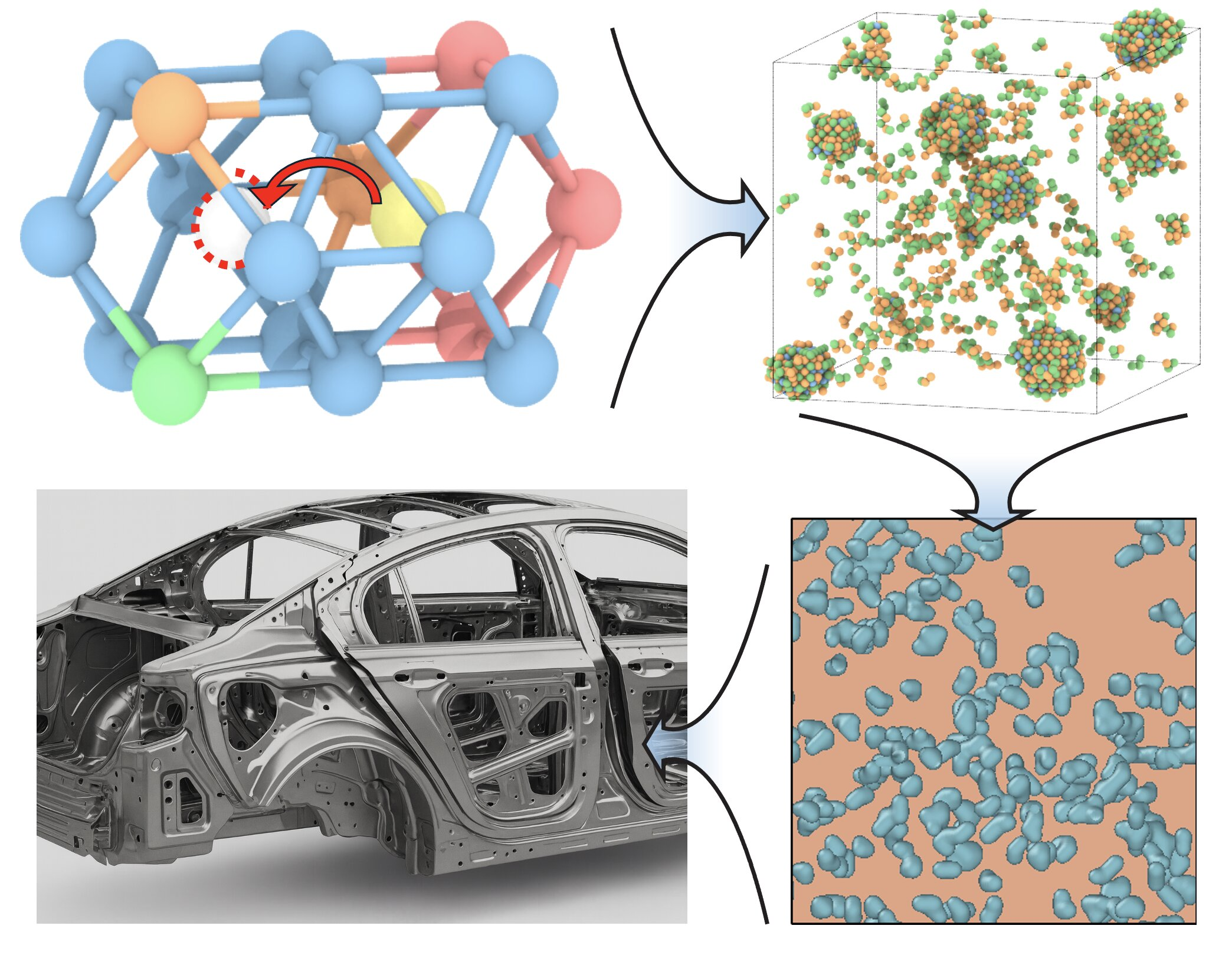

High-strength aluminum alloys play a crucial role in modern engineering, especially in efforts to make cars and airplanes lighter, stronger, and more fuel-efficient. Yet despite their potential, some of the strongest aluminum alloys remain difficult and expensive to manufacture consistently. A new study led by researchers at the University of Michigan, working closely with General Motors Research & Development, offers a promising solution: a predictive, multiscale computational model that explains exactly how cooling and aging processes influence alloy strength—and how manufacturers can optimize them.

At the center of this research are 7000-series aluminum-magnesium-zinc (Al-Mg-Zn) alloys, materials originally developed for aerospace applications. These alloys are prized for their exceptional strength-to-weight ratio, but their complex processing requirements have limited their widespread use in the automotive industry. The new model provides a way to predict and control those processes with far greater precision than ever before.

Why High-Strength Aluminum Alloys Matter

Reducing vehicle weight is one of the most effective ways to improve fuel efficiency and reduce emissions. Aluminum alloys are attractive alternatives to steel because they are significantly lighter while still offering high strength. Among them, 7000-series Al-Mg-Zn alloys stand out due to their ability to achieve extremely high strength through precipitation hardening.

However, this strength comes at a cost. These alloys are notoriously difficult to process consistently, especially during a phase known as natural aging, which occurs at room temperature after the alloy has been quenched. Small variations in processing can lead to large differences in mechanical properties, making large-scale manufacturing risky and expensive.

The Core Manufacturing Challenge

To strengthen Al-Mg-Zn alloys, manufacturers follow a multi-step process:

- The alloy is heated to around 500°C, dissolving magnesium and zinc atoms into the aluminum matrix.

- The material is then rapidly cooled in a process called quenching.

- Finally, the alloy is left to age naturally at room temperature, typically for one to three days.

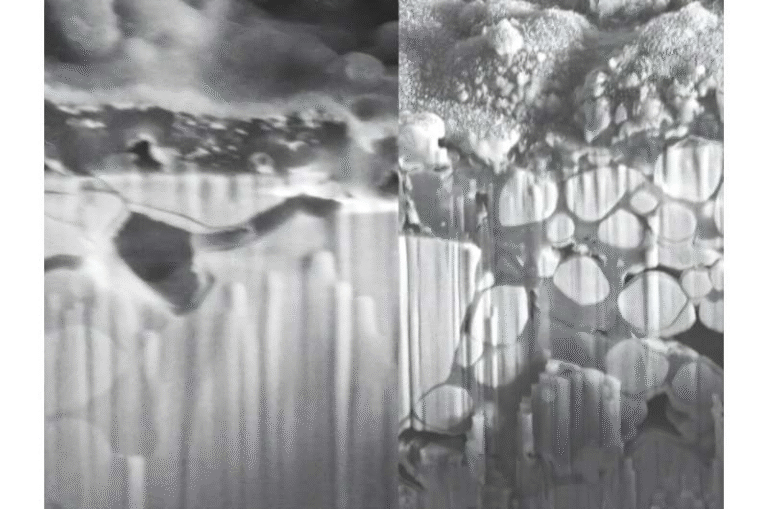

During quenching, cooling happens so quickly that atoms do not have enough time to rearrange themselves into their most stable positions. This creates vacancies, or missing atoms, in the crystal structure. These vacancies are not just defects—they actively influence how magnesium and zinc atoms move, cluster, and eventually form precipitates, which are the tiny reinforcing structures that give the alloy its strength.

The problem is that vacancy behavior during natural aging is extremely complex and hard to predict.

Why Traditional Modeling Falls Short

At the atomic level, vacancies move by hopping between neighboring atoms, and each hop depends on the local chemical environment. In a multicomponent alloy like Al-Mg-Zn, the number of possible atomic configurations becomes enormous. Traditional atomistic simulations, such as kinetic Monte Carlo methods, struggle to simulate more than a few seconds of real time.

Natural aging, however, unfolds over hours or days. This mismatch between simulation capability and real-world timescales has made it nearly impossible to predict aging behavior accurately without extensive trial-and-error experiments.

A Multiscale Solution to a Multiscale Problem

The research team addressed this challenge by developing a multiscale modeling framework that bridges atomic-scale physics with long-term aging behavior. Instead of tracking every individual atom, the model simplifies vacancy motion into a statistically guided process.

At the atomic level, the researchers used a Markov chain approach to describe how long vacancies remain trapped inside solute clusters. Vacancy motion is treated as a guided random walk across an energy landscape, capturing the essential physics without overwhelming computational cost.

These atomic-scale insights are then fed into a mesoscale cluster-dynamics model, which predicts how magnesium-zinc clusters evolve over time. This combination allows the simulation of hours or even days of aging in just minutes of computation, a dramatic improvement over conventional methods.

The Discovery of a Vacancy “Fingerprint”

One of the most important findings of the study is that the quench rate leaves behind a long-lasting vacancy fingerprint that controls natural aging behavior.

- Faster cooling traps a higher number of mobile vacancies in the aluminum matrix. These vacancies accelerate solute diffusion and lead to faster cluster formation during natural aging.

- Slower cooling allows larger precipitates to form during quenching itself. These precipitates trap vacancies, reducing their mobility and extending the aging process.

This means that cooling speed doesn’t just affect the alloy immediately—it influences microstructural evolution days later. The model shows how subtle changes in quench rate can dramatically alter the size, distribution, and growth rate of strengthening precipitates.

Why This Matters for Automotive Manufacturing

Aerospace manufacturers have long avoided the unpredictability of natural aging by using costly workarounds, such as high-temperature deformation or low-temperature storage. While effective, these methods are impractical for high-volume car production.

The new modeling framework offers a path to simpler, more predictable processing, making it easier to integrate high-strength aluminum alloys into automotive body structures. Instead of relying on expensive experimentation, engineers can now simulate how changes in chemistry, cooling, and aging will affect final material properties.

This approach significantly reduces development time and manufacturing risk while improving consistency.

Broader Implications for Materials Science

Beyond aluminum alloys, the framework represents a major advance in computational materials engineering. Vacancy-cluster interactions play a critical role in many advanced alloys used for lightweight and sustainable manufacturing, including those found in energy, aerospace, and defense applications.

By linking atomic behavior to macroscopic properties across length and time scales, the model demonstrates how physics-based simulations can replace large portions of experimental trial and error. This aligns closely with broader goals in materials science, such as integrated computational materials engineering (ICME) and data-driven alloy design.

Understanding Vacancies and Precipitates in Simple Terms

Vacancies may sound like flaws, but they are essential actors in alloy strengthening. They act as transport vehicles, helping solute atoms migrate and cluster. Precipitates, once formed, block dislocation motion, which is what gives metals their strength.

The balance between vacancy mobility and cluster stability determines how strong—and how workable—the final alloy becomes. This study shows that by controlling vacancies early in processing, engineers can guide the entire aging pathway.

A Practical Tool for Designing Better Materials

The new model doesn’t just explain why processing has been unpredictable—it provides a quantitative roadmap for improvement. By capturing vacancy–cluster interactions across multiple scales, researchers can now predict aging behavior that once required extensive experimentation.

This opens the door to more efficient material design, better use of high-strength aluminum in everyday vehicles, and a future where advanced alloys are engineered with precision rather than guesswork.

Research Paper Reference:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41524-025-01840-x