Physicists Achieve Near-Perfect Quantum Control Over Molecules, Opening New Doors for Quantum Technology

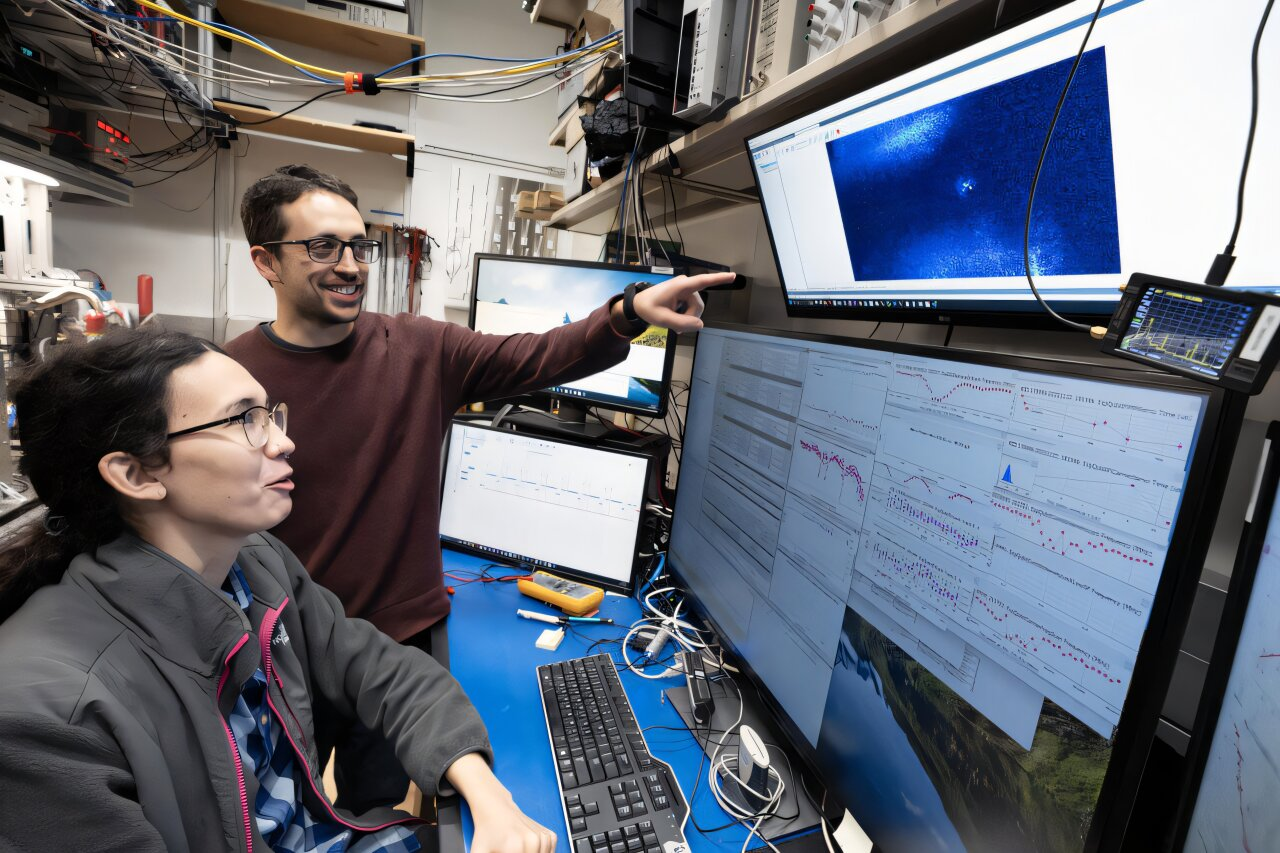

Physicists have spent decades learning how to precisely control individual atoms, turning them into the backbone of modern quantum technologies such as atomic clocks, quantum sensors, and early quantum computers. Now, researchers have taken a major step beyond atoms and into far more complex territory: molecules. In a new breakthrough, scientists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have demonstrated near-perfect quantum control of a molecular ion, overcoming one of the most stubborn challenges in quantum physics.

This achievement marks an important milestone because molecules, while more difficult to tame, offer far richer possibilities than atoms for sensing, computation, and fundamental physics research.

Why Molecules Matter More Than Atoms in Quantum Science

Atoms are relatively simple. From a quantum perspective, many atoms behave like tiny spheres: rotate them any way you want, and they still look the same. This symmetry makes atoms easier to control with lasers and electromagnetic fields.

Molecules, on the other hand, are fundamentally different. Even the simplest molecule can rotate, vibrate, and stretch, creating a dense and complicated landscape of quantum states. These additional degrees of freedom make molecules extremely sensitive to their surroundings, including temperature and electromagnetic radiation.

This sensitivity can be a double-edged sword. On one hand, it makes molecules harder to control because environmental disturbances can easily knock them out of a desired quantum state. On the other hand, that same sensitivity makes molecules exceptionally powerful tools for precise measurements and sensing applications.

The challenge has always been control—and that is exactly what this new work addresses.

The Molecule at the Center of the Experiment

The NIST team focused on a calcium hydride molecular ion, written chemically as CaH⁺. This molecule consists of one calcium atom and one hydrogen atom, with a single electron removed, giving it a positive charge. That charge allows the molecule to be trapped and manipulated using electromagnetic fields.

Unlike atoms, calcium hydride has a lopsided, dumbbell-like structure, meaning its orientation in space matters. Each rotational state represents a distinct quantum configuration, and precisely controlling those states is essential for using molecules in quantum technologies.

The Core Problem: Molecules Don’t Cooperate With Lasers

One of the biggest hurdles in molecular quantum control is that most molecules do not interact cleanly with lasers. Atoms can often be directly cooled, excited, and measured using laser light. Molecules, with their many internal energy levels, tend to absorb and emit light in messy ways that are difficult to exploit.

To get around this, the researchers used an indirect but highly effective method known as quantum logic spectroscopy.

How Quantum Logic Spectroscopy Solves the Problem

Quantum logic spectroscopy is a technique originally developed to improve ultra-precise atomic clocks. Instead of directly probing a difficult-to-control particle, scientists pair it with a second particle that is easier to manipulate.

In this experiment, the molecular ion was trapped alongside a single calcium ion, which acts as a helper or “logic” ion. Because both ions carry the same electric charge, they repel each other and remain coupled through their shared motion inside the trap.

The calcium ion interacts very cleanly with lasers. By cooling and manipulating the calcium ion, the researchers could indirectly cool and control the molecular ion as well. This process is known as sympathetic cooling, and it is crucial for preparing the molecule in a well-defined quantum state.

Cooling the Molecule and Locking in Its Quantum State

The experiment was conducted in a cryogenic environment, meaning extremely cold temperatures. This reduced unwanted thermal radiation that would otherwise disturb the molecule.

Once cooled, the researchers used lasers to drive changes in the rotational state of the calcium hydride molecule. The molecule itself does not visibly respond, but the calcium ion does. Whenever the molecule’s rotational state changes, the calcium ion reacts by emitting a tiny burst of light—a visible flash detected by the researchers’ camera.

By observing these flashes, the scientists could determine whether the molecule had successfully transitioned between quantum states.

A Remarkable Level of Precision

The results were striking. The team demonstrated a 99.8% success rate in preparing, controlling, and verifying the molecule’s rotational quantum state. In practical terms, this means that out of 1,000 attempts, only about two failed.

Even more impressive was how long the molecule remained stable. Once prepared, the calcium hydride molecule stayed in its designated rotational state for about 18 seconds before thermal radiation caused it to change. In the quantum world, where disturbances often happen in fractions of a second, 18 seconds is an exceptionally long time.

This long lifetime allowed the researchers to repeatedly check the molecule’s state, confirming that the observed behavior was genuine and not a random fluctuation.

Molecules as Ultra-Precise Quantum Thermometers

One unexpected outcome of the experiment was the molecule’s ability to act as a highly sensitive thermometer. The molecule responded to surrounding thermal radiation with far greater sensitivity than the conventional temperature sensors inside the vacuum chamber.

This opens the possibility of using molecules as quantum thermometers, capable of detecting not just temperature but even the frequency distribution of thermal radiation. Such tools could be invaluable for improving atomic clocks, where tiny temperature variations can limit accuracy.

Expanding the Quantum Toolbox Beyond Atoms

Until now, most quantum technologies have relied on a small set of atomic ions, such as calcium or barium. Molecules vastly expand the available options. While the periodic table contains a finite number of usable atoms, the number of possible molecules is nearly limitless.

The techniques demonstrated in this experiment are not specific to calcium hydride. In principle, the same protocol could be applied to many other molecular species, allowing scientists to choose molecules tailored to specific tasks in quantum sensing, quantum information processing, and fundamental physics experiments.

What This Means for the Future

This work does not mean molecular quantum computers or perfectly controlled chemistry are right around the corner. The researchers are careful to emphasize that this is a foundational demonstration, not a finished technology.

However, it is a powerful proof that molecules—long considered too unruly for precise quantum control—can be tamed with the right tools. By combining cryogenic environments, quantum logic spectroscopy, and sympathetic cooling, scientists now have a reliable way to harness the unique advantages of molecules.

As quantum research continues to push beyond atoms, this breakthrough significantly broadens what is possible, offering access to a much richer and more versatile quantum world.

Research Paper Reference:

Dalton Chaffee et al., High-Fidelity Quantum State Control of a Polar Molecular Ion in a Cryogenic Environment, Physical Review Letters (2025).

https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.14740