Ultrashort Laser Pulses Reveal How Molecules Interact Inside Liquids at the Fastest Timescales

Liquids may look simple on the surface, but at the molecular level they are anything but. Every liquid is a constantly shifting environment where molecules move, collide, and interact in complex ways. Whether it’s sugar dissolving in water or proteins floating inside a living cell, these tiny interactions shape chemistry, biology, and materials science. Yet for decades, scientists have struggled to observe what really happens inside liquids at the level of individual molecules and electrons.

A new study from researchers at Ohio State University (OSU) and Louisiana State University (LSU) offers a breakthrough. Using ultrashort laser pulses and a technique called high-harmonic spectroscopy (HHS), the team has managed to directly probe how molecules interact in liquid mixtures, capturing effects that occur on attosecond timescales—that’s a billionth of a billionth of a second. The results were published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) and mark an important step forward in liquid-phase science.

Why Liquids Are So Hard to Study

Unlike solids, which have fixed structures, or gases, where molecules are far apart, liquids exist in a middle ground. Molecules in a liquid are tightly packed but constantly moving. This lack of stable structure makes it extremely difficult to track how electrons behave and how molecules influence one another during chemical interactions.

Traditional optical spectroscopy has long been the go-to method for studying liquids because it is gentle and relatively easy to interpret. However, it operates on much slower timescales and cannot capture the fastest electron dynamics. Those ultrafast processes are where many important chemical reactions actually begin.

This is where high-harmonic spectroscopy comes in.

What Is High-Harmonic Spectroscopy?

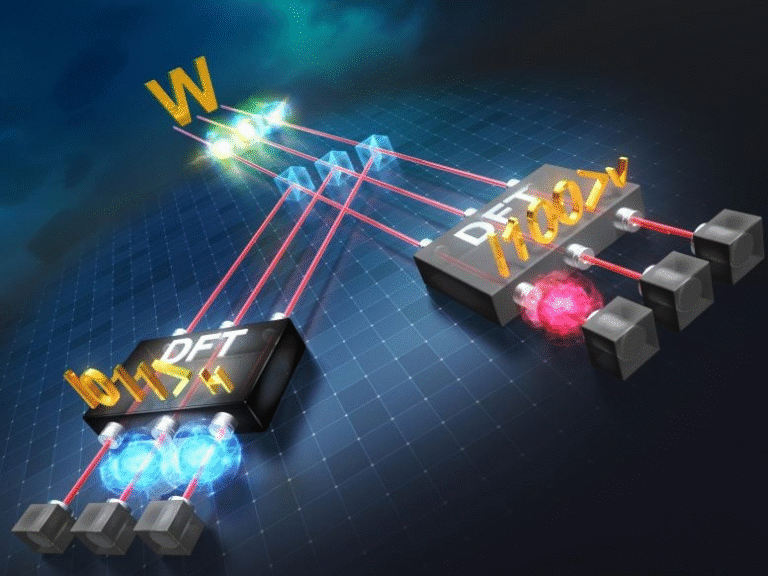

High-harmonic spectroscopy is a nonlinear optical technique that uses intense, ultrafast laser pulses to briefly pull electrons away from molecules. When the electrons snap back, they emit light at multiples—or harmonics—of the original laser frequency. By analyzing this emitted light, scientists can infer how electrons and even atomic nuclei move on incredibly short timescales.

HHS offers attosecond-level resolution, making it one of the fastest tools available for studying matter. Until now, however, it has mostly been limited to gases and solids, where experiments are easier to control. Liquids posed two major challenges: they strongly absorb the emitted harmonic light, and their constantly changing molecular arrangements make the signals hard to interpret.

A Technical Breakthrough for Studying Liquids

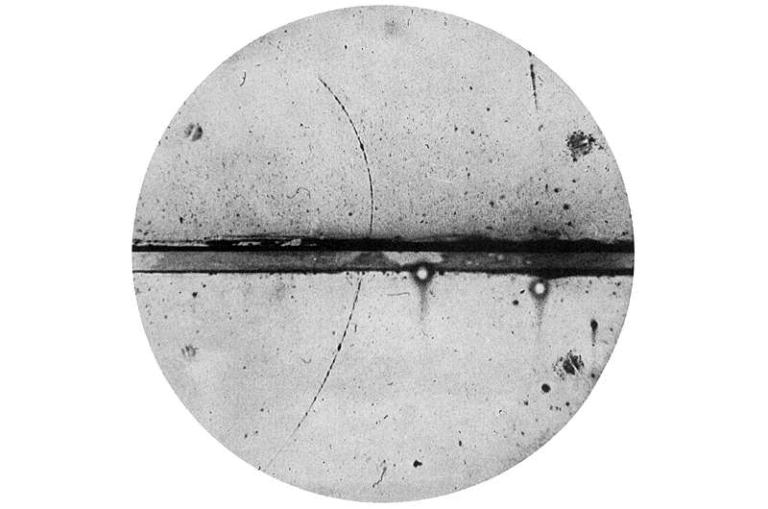

To overcome these obstacles, the OSU–LSU team developed an ultrathin liquid sheet, allowing more of the harmonic light to escape before being reabsorbed. This innovation made it possible, for the first time, to apply high-harmonic spectroscopy to liquid solutions in a meaningful way.

With this setup, the researchers could finally test whether HHS could detect local molecular structures that form when one liquid dissolves into another. The answer turned out to be yes—and in a surprising way.

Testing Simple Liquid Mixtures

The team focused on mixtures of methanol with small amounts of halobenzenes. These molecules are nearly identical, differing only by a single atom attached to a benzene ring: fluorine, chlorine, bromine, or iodine. This made them an ideal test case because any differences in behavior could be traced back to subtle chemical effects rather than large structural changes.

Halobenzenes are known to produce strong harmonic signals, while methanol provides a clean background. The researchers expected that, even in dilute mixtures, the harmonic emission would largely resemble a simple combination of the two liquids.

That expectation held true for most mixtures—but not all.

The Fluorobenzene Surprise

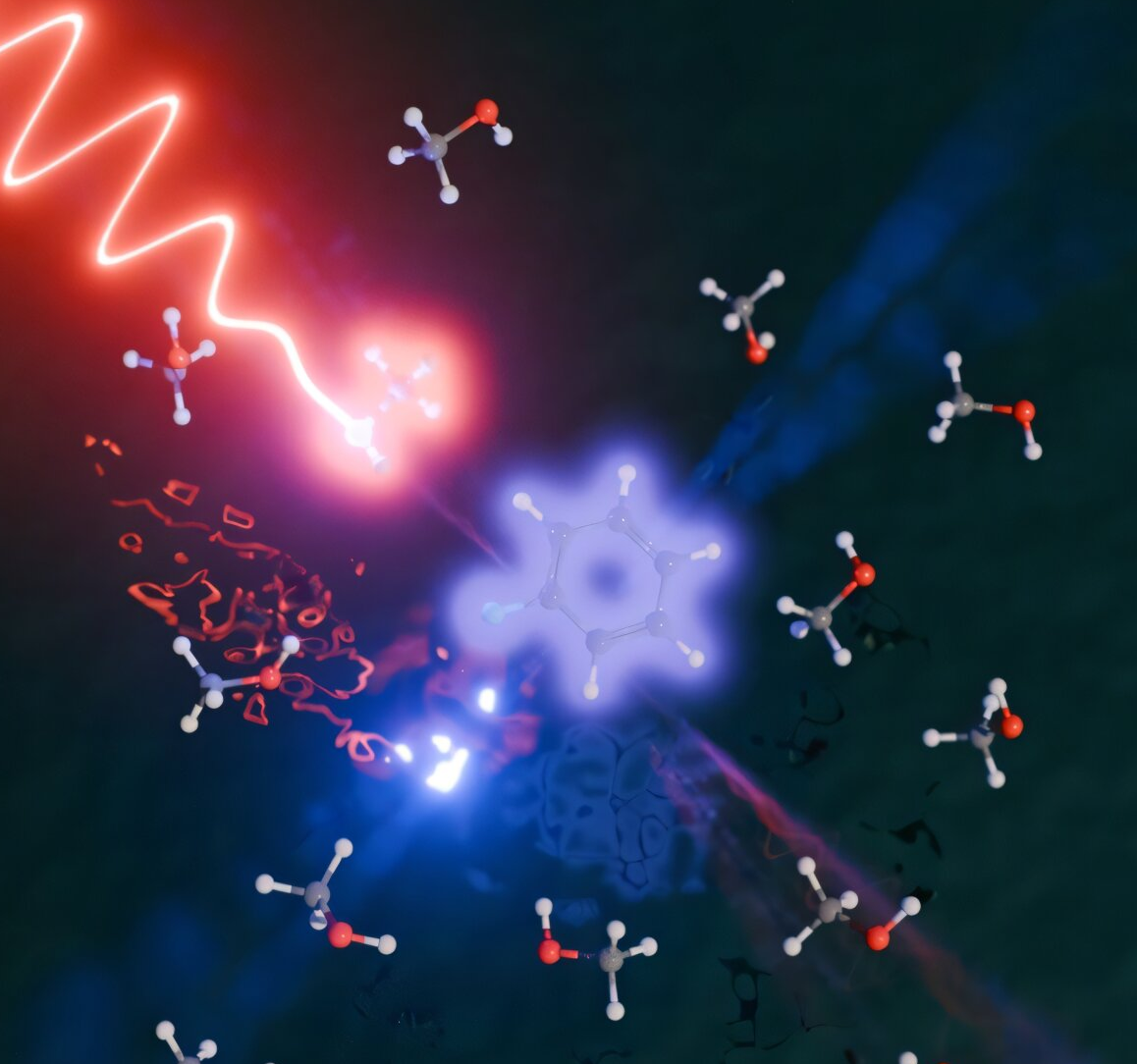

When fluorobenzene was mixed with methanol, the results were dramatically different. Instead of producing a combined signal, the mixture generated less harmonic light than either liquid alone. Even more striking, one specific harmonic frequency was completely suppressed, as if a single note in the spectrum had been silenced.

This kind of selective suppression is extremely rare and pointed to destructive interference in the harmonic generation process. In simple terms, something near the emitting molecules was blocking or scattering the electrons in a very specific way.

This unexpected behavior hinted at a unique molecular interaction happening inside the fluorobenzene–methanol solution.

The Molecular “Handshake”

To understand what was going on, the OSU theory team ran large-scale molecular dynamics simulations. These simulations revealed that fluorobenzene behaves differently from the other halobenzenes when dissolved in methanol.

The key lies in the electronegativity of fluorine. The fluorine atom promotes a strong interaction with the oxygen–hydrogen end of methanol, forming a hydrogen-bond-like interaction. This creates an organized local arrangement—a kind of molecular handshake—that does not form in mixtures with chlorine, bromine, or iodine.

In those other cases, the halobenzene molecules are distributed more randomly, leading to ordinary harmonic emission. Fluorobenzene, however, induces a specific solvation structure that alters how electrons move during the high-harmonic process.

Confirming the Physics Behind the Effect

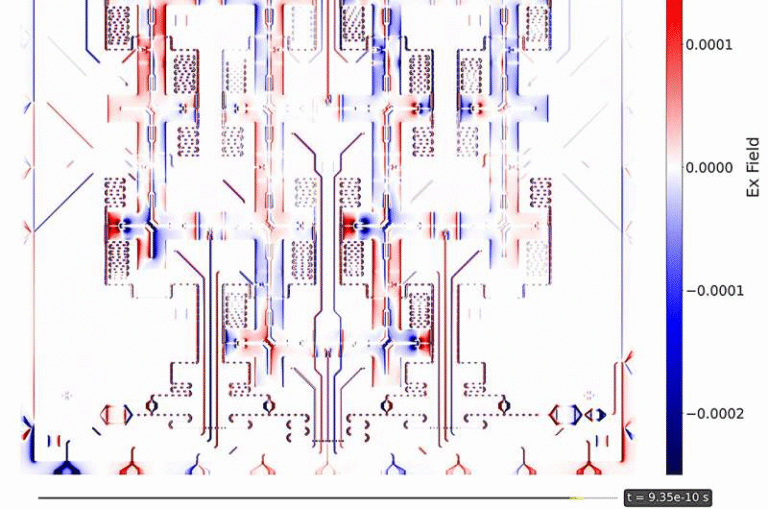

The LSU theory team took the analysis further by modeling the system using the time-dependent Schrödinger equation, a fundamental equation of quantum mechanics. Their calculations showed that the electron density around the fluorine atoms acts as a scattering barrier.

As electrons are driven by the laser field and attempt to return to their parent molecules, this barrier disrupts their trajectories. The result is both the suppressed harmonic and the reduced overall harmonic yield observed in the experiment.

Importantly, the simulations also revealed that the suppression is highly sensitive to the exact position of the scattering barrier. This means the harmonic spectrum itself carries detailed information about the local liquid structure, offering a new way to probe solute–solvent interactions.

Why This Matters Beyond This Experiment

This study demonstrates, for the first time, that solution-phase high-harmonic generation can be sensitive to specific molecular interactions in liquids. That opens the door to studying a wide range of systems where chemistry happens in liquid environments.

Many chemical reactions, biological processes, and radiation-induced effects occur in liquids. The electron energies involved in high-harmonic generation are similar to those responsible for radiation damage, making this research relevant not just for basic science but also for applied fields like medicine and materials science.

A Broader Look at Liquids and Electron Dynamics

Liquids dominate both nature and industry, yet they remain one of the least understood states of matter at ultrafast timescales. Techniques like HHS now provide a way to directly observe how electrons scatter, how local structures form, and how these effects influence chemical behavior.

As experimental methods improve and simulations grow more powerful, researchers expect to apply this approach to more complex liquids, including biologically relevant systems. The long-term goal is to extract detailed structural and dynamical information directly from harmonic spectra, without relying solely on indirect measurements.

Looking Ahead

While this study focused on relatively simple mixtures, its implications are broad. It shows that ultrafast laser techniques can move beyond gases and solids and into the messy, dynamic world of liquids. More importantly, it proves that even subtle molecular interactions can leave a clear fingerprint when viewed on the right timescale.

High-harmonic spectroscopy in liquids is still in its early days, but this work suggests it could become a powerful tool for understanding chemistry where it most often happens—in solution.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2514825122