A New Quantum Chemistry Method Is Bringing Chemists and Physicists Closer Than Ever

Scientists at the University of Chicago have developed a powerful new quantum chemistry method that could dramatically improve how researchers understand and design advanced materials. From high-temperature superconductors to solar cell semiconductors, the approach tackles a long-standing problem in materials science: how to accurately describe electrons that behave both locally and across an entire solid.

This new work, published in Nature Communications in 2025, introduces a way to finally bridge two scientific perspectives that have remained largely separate for decades—quantum chemistry and solid-state physics. By uniting these views into a single, rigorous framework, the method opens up fresh possibilities for studying materials whose properties have been notoriously difficult to model.

Why Modeling Advanced Materials Has Been So Difficult

When scientists study solids, they usually fall into one of two camps. Physicists tend to describe materials using band theory, where electrons are spread across a repeating crystal lattice and treated as delocalized waves. Chemists, on the other hand, often focus on localized electrons, analyzing how they behave within specific molecules or fragments of a material.

Both perspectives work well in certain situations—but many real-world materials don’t fit neatly into either framework.

Materials such as organic semiconductors, metal–organic frameworks, and strongly correlated oxides sit awkwardly between these two descriptions. In these systems, electrons are neither fully spread out nor completely confined. Instead, they often behave as if they are hopping between repeating molecular fragments, retaining local character while still influencing global electrical behavior.

Traditional methods struggle here. If researchers focus only on local chemistry, they lose track of how charges move across the entire material. If they rely purely on band theory, they miss important local electron interactions that strongly affect material properties.

This gap is exactly what the new method aims to close.

The Core Idea Behind the New Method

The new approach builds on a framework called Localized Active Space (LAS), originally developed by Matthew Hermes, a research assistant professor at the University of Chicago. LAS was first designed to handle complex molecular systems, allowing scientists to treat different parts of a molecule with high-level quantum accuracy while keeping calculations manageable.

The breakthrough came when the research team extended LAS to periodic solids, meaning materials that repeat infinitely in space. This extension transforms LAS into a hybrid quantum chemistry and band-theory method, capable of handling both local electron correlations and global electronic structure at the same time.

In practical terms, the method lets researchers:

- Model individual fragments of a material with detailed quantum chemistry

- Capture how electrons move between fragments

- Preserve the overall band structure that governs conductivity and optical behavior

This combination allows scientists to “see” materials in a way that was previously out of reach.

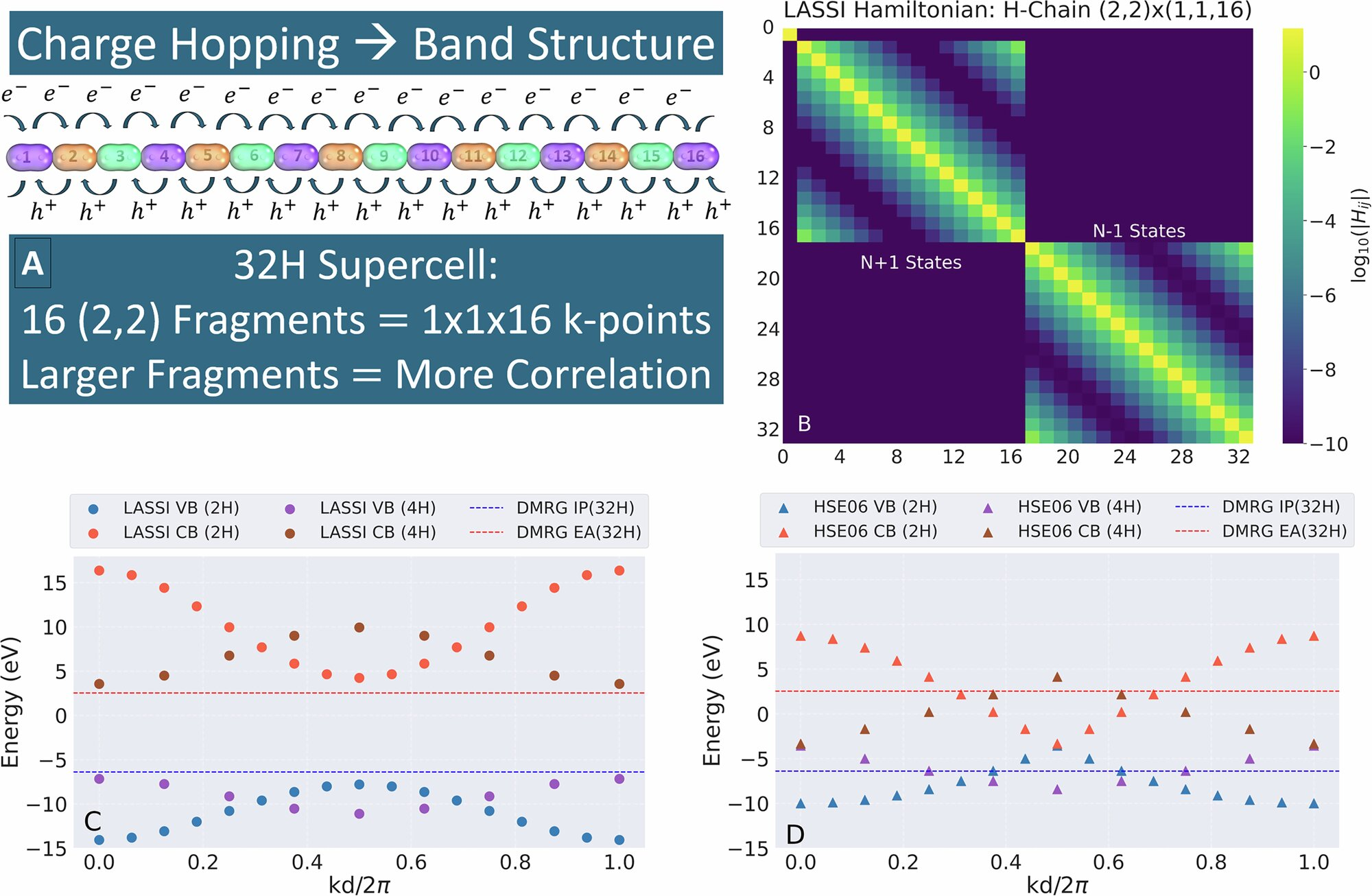

Hydrogen Chains as a Crucial Test Case

To prove the method works, the team tested it on systems that have long challenged existing approaches. One classic example is hydrogen chains.

Hydrogen chains might sound simple, but they have caused major headaches for computational chemists and physicists alike. Standard density functional theory (DFT) methods often predict that stretched hydrogen chains behave like metals. More accurate theoretical treatments, however, show that they should act as insulators due to strong electron localization.

Using the extended LAS approach, the researchers were able to correctly reproduce the insulating behavior of hydrogen chains. The method accurately captured how electrons localize on individual hydrogen atoms while still accounting for their collective interactions across the chain.

This result was an important validation, showing that the method gets the underlying physics right where other popular techniques fail.

Simulating a p–n Junction With Quantum Accuracy

Another striking demonstration involved a p–n junction, a fundamental building block of solar cells, LEDs, and computer chips.

A p–n junction forms when two types of semiconducting materials—one rich in positive charge carriers and the other rich in negative carriers—are brought together. When light hits the junction, charges separate and flow, creating electrical current.

Capturing this process at the quantum level is extremely challenging. Many methods either oversimplify charge separation or cannot describe electron movement across the junction accurately.

The LAS-based method successfully simulated how charges separate and move across the p–n junction when exposed to light. This level of detail offers valuable insight into processes that are central to modern electronics and renewable energy technologies.

What Makes This Method Especially Powerful

One of the most important aspects of this work is its flexibility. The researchers emphasize that this is only a first step. The LAS framework can be combined with other advanced quantum methods to further improve accuracy and expand its range of applications.

Because the approach is rooted in rigorous quantum mechanics, it avoids many of the approximations that limit existing techniques. At the same time, it remains computationally feasible for real materials, which is critical for practical use.

The method is also designed to be a tool for both understanding and design. Scientists can use it to analyze why a material behaves the way it does—and eventually to predict how new materials might behave before they are ever synthesized in a lab.

Why This Matters for Future Materials

All materials are governed by quantum mechanics at their core. Yet, for many technologically important materials, researchers still rely on simplified models that miss crucial details.

By uniting local quantum chemistry with global band behavior, this new method offers a clearer, more complete picture of how electrons truly behave in complex solids. That clarity could have major implications for:

- Designing better superconductors

- Improving solar cell efficiency

- Understanding strongly correlated materials

- Developing next-generation quantum and electronic devices

The researchers also point out that the method is intended to be open and extensible, encouraging adoption and improvement by the broader scientific community.

A Bit of Background on Localized Active Spaces

For readers less familiar with quantum chemistry, it’s worth briefly explaining why localized active spaces matter.

In quantum chemistry, the “active space” refers to the subset of electrons and orbitals treated with the highest level of accuracy. Traditional methods often require a single, large active space, which quickly becomes computationally impossible for big systems.

LAS breaks this problem apart by assigning multiple localized active spaces to different fragments of a system. Each fragment is treated accurately, and their interactions are carefully combined. Extending this idea to periodic solids is what makes the new method so significant.

Looking Ahead

This research represents an elegant and important step toward a more unified view of materials. Instead of choosing between chemical intuition and physical band theory, scientists can now use a method that respects both.

As computing power grows and quantum methods continue to improve, approaches like this could become central to how advanced materials are studied and designed. For now, the work stands as a strong example of what happens when long-separated scientific ideas are finally brought together.

Research Paper:

Daniel S. King et al., Bridging the gap between molecules and materials in quantum chemistry with localized active spaces, Nature Communications (2025).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65846-1